What makes art and design representative of the working-class experience?

Abstract

"According to the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, only 16% of individuals from working-class backgrounds are employed in creative roles across the UK" (Lewis, 2021). This statistical disparity raises important questions regarding the underrepresentation of working-class individuals within the creative sector. This discourse aims to explore the term 'working-class creative' and elucidate how we categorise art and design that can be deemed representative of working-class backgrounds.

Numerous factors contribute to the authenticity of a piece of work as being indicative of working-class identity; however, these factors are frequently overlooked within the broader creative discourse. By delineating the discussion into three subsections-The Artist, The Artwork, and The Audience-this analysis seeks to unpack the complexities surrounding each theme and the multifaceted variables that must be considered when evaluating whether a piece of artwork can be classified as working-class. Each section will also examine the challenges of defining social class, utilising case studies involving figures such as Alexander McQueen, Martin Parr, and the historical context of union strikes to illustrate the implications of these factors in real-world scenarios. Through a thorough investigation of these examples, this dissertation aims to provide critical insights into how social class influences perceptions within creative industries. By inviting new ways of thinking, this exploration will encourage open dialogue about the systemic challenges faced by working-class individuals in the creative sector, thereby fostering a deeper understanding of their underrepresentation.

Introduction

Within the fields of art and design, the discourse surrounding social class is frequently omitted or navigated with caution. This silence is attributable to the complexities inherent in defining the concept of class and the various social hierarchies that accompany it. This leads to many individuals preferring to sidestep the discussion to mitigate the risk of misinterpretation. Nevertheless, social class emerges as a critical and pertinent factor in creative contexts. "According to the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, only 16% of individuals from working-class backgrounds are employed in creative roles across the UK" (Lewis, 2021). This striking statistic emphasises a significant lack of diversity and representation within creative sectors, prompting a vital inquiry into whether the art and design industry can truly claim to be an inclusive and equitable domain.

The underrepresentation of working-class individuals within these fields invites a critical examination of the nature and intent behind the artistic works produced. This analysis will categorise working-class art and design into three distinct sections, each exploring how various class-related factors inform the creation of artistic work. The first section, 'The Artist,' interrogates whether an artist must possess a working-class background to authentically produce work that reflects working-class experiences, thereby considering the implications of the artist's identity on their creative output. The second section, 'The Artwork,' examines the visual language of the artwork and whether it is inherently required to resonate with working-class audiences, focusing on how working-class representations are constructed within the art. The final section, 'The Audience,' explores strategies for effectively engaging working-class viewers, this analyses the numerous ways in which audience demographics influence the artist's approach to creating work that speaks to working-class experiences.

Through this dissertation, a nuanced understanding of the intricacies of working-class design will be developed, explaining the relationship of various real-world factors while acknowledging the influences that lie outside the artist's immediate control.

Chapter 1: 'The Artist'

How do we define working-class? According to the Oxford Dictionary, it is "the social group consisting primarily of people who are employed in unskilled or semi-skilled manual or industrial work" (Simpson, 2002). But how accurate is this definition and how has it changed over time? Can something as intricate as class be distilled into a single sentence? Jamie Jackson, a writer who explores the topic of social class, argues that "being working-class isn't about money; it's about mentality." (Jackson, 2023). This perspective challenges the common misconception that financial status defines class, suggesting instead that it revolves around an individual's mindset and the values they hold. Jackson's argument dismantles entrenched stereotypes about working-class individuals and encourages a deeper examination of the foundations of class. He elaborates, "It's about ambition, or lack thereof; it's about knowing your place; being ignorant about money, savings, investments, and job markets..." (Jackson, 2023). Such insights prompt readers to reconsider what truly constitutes working-class identity. Class is multifaceted and perceived differently by each individual, often shaped by their upbringing. An examination of the definition of "working class" reveals that the term is not a singular or concrete entity, but rather a construct that stems from a diverse array of experiences that individuals within a similar socioeconomic status share. While the concept of working class implies a collective identity, it is crucial to recognise that individuals categorised as working class do not all share identical experiences. The collection of individual narratives and circumstances suggests that, despite their classification as working class, individuals may encounter vastly different life events and challenges. So, can working-class status be defined solely by financial means? No. The working class embodies much more complexity and depth than a simple economic classification allows, the uniqueness of working-class identity lies in its varied interpretations. While economic factors play a role, it is ultimately the working-class mindset, values and experiences that represent the underlying strength of working-class life, often overlooked in popular discourse.

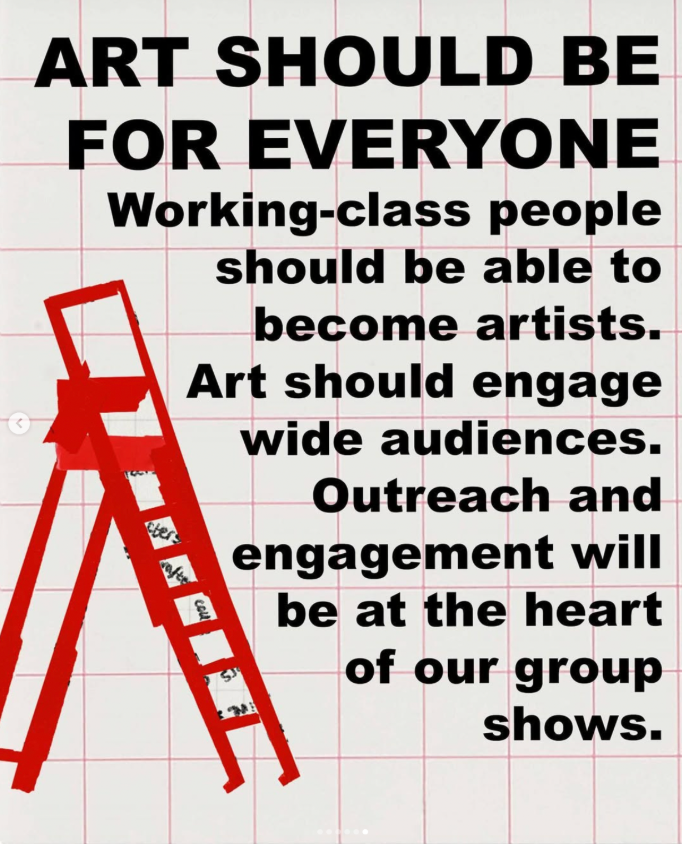

Figure 1 – Grafters Collective Manifesto

The concept of working-class identity is inherently complex and subject to various interpretations, particularly within the context of creative disciplines. This complexity invites an examination of how individuals, engaged in artistic practice, may authentically label themselves as working-class artists or designers. Central to this inquiry is the question of which values and experiences must be adhered to in order to ethically assume this identity. In pursuit of a deeper understanding, I engaged in dialogues with several artists and designers who self-identify as working-class, aiming to delineate the criteria that underpin this classification. The primary objective is to explore the adaptability of the term 'working-class' when contextualised within creative practices. Jennifer Jones, the curator of a collective of working-class artists 'GRAFTERS', articulates that "class is complex and the identity surrounding it is problematic." (Jones, 2024.) She highlights that not all individuals who have faced barriers due to their socioeconomic background may find resonance with this term. Jones emphasises the significant role played by one's upbringing and environment in shaping their identity, illustrating that many self-identified working-class artists have typically navigated the lived experiences associated with such a background. This lived experience is relevant to working-class individuals across various professions; however, the unique challenges faced within the creative sector amplify these complexities.

Dan Fox, a writer who has experienced classism within the art world, states, "Art is for everyone, but participation in its professional systems is not." (Fox, 2016.) This invites an exploration of the way class functions as a significant determinant within the art world, raising questions about the implications of class stratification in artistic professions. In analysing the dynamics of class within the art sector, it becomes evident that many institutions and spaces are predominantly occupied by middle-class individuals, resulting in a conspicuous underrepresentation of working-class artists. The ramifications of this imbalance extend beyond professional opportunities; they also significantly influence the nature and breadth of artistic output. When a singular class group dominates this cultural sphere, the authenticity of artistic expression is called into question, as the resultant art may reflect the experiences and values of middle-class individuals rather than diverse lived experiences. Fox expands on this, stating, "class diversity has an effect on the type of art that gets made in a place and the kinds of conversations that can be found there." (Fox, 2016). This observation highlights the impact of class on artistic production and discourse in the absence of working-class artists, the conversation surrounding class issues may be severely diminished as the narratives from middle-class perspectives become the default. Working-class creatives often face limited support due to familial concerns about the financial stability of artists careers. This dynamic directly informs the aspirations of working-class individuals pursuing creative vocations, as they frequently grapple with financial constraints that impede their artistic endeavours. Consequently, a palpable divide emerges between working-class artists and their middle- and upper-class counterparts, who are less likely to encounter similar material limitations. This disparity exemplifies how class shapes the landscape of creative professions, complicating the pursuit and expression of artistic identity.

Social mobility complicates the understanding of class significantly. Once labelled as working class, one may wonder how that identity persists throughout their career. If an individual earns a higher wage, but no longer fits the traditional Oxford English Dictionary definition, how do they classify themselves? Beth Ashley, a working-class journalist who experienced class mobility after art school, examines this issue and notes, "I was earning more than most of my family members - a realisation that brought a confusing mix of relief, guilt, and fear that I was a 'class traitor.'"(Ashley, 2021). She delves into the notion that individuals may feel caught between the working class and middle class, as they retain a working-class mindset despite lacking the financial struggles typically associated with that identity. This dynamic complicates the definition of working-class artists further. Commonly, it is assumed that financial advancement leads to a complete transformation of attitudes, aesthetics, and lifestyle, but this assumption is flawed. Navigating one's place within the class system can be challenging after experiencing social mobility.

An illustrative example of how social mobility can significantly influence an individual's mindset and attitudes is the renowned fashion designer Alexander McQueen. McQueen began his career in a modest tailoring shop, later studying fashion at Central Saint Martins. (McQueen and I, 2018). With the mentorship of Isabella Blow, he rapidly began showcasing his designs on catwalks immediately after graduating. Notably, during this period, he relied on unemployment benefits, candidly stating that he "bought his fabrics with my dole money." (McQueen, 1992). This raises questions about the intersections of social mobility and identity; although McQueen was working-class and fresh from higher education, the utilisation of public funds to support his career ambitions poses a moral dilemma regarding fairness in the pursuit of success. This trajectory is deeply intertwined with class dynamics, as he emerged from a working-class background, lacking formal qualifications and residing in a public housing estate. His admission to Central Saint Martins was not predicated on prior academic achievements but rather on his practical experience gained at the tailoring shop. This situation underlines the notion of social mobility: McQueen began at a disadvantaged position and, through his tenacity, ascended to a prominent place in the fashion industry.

Figure 2 - Alexander McQueen

Further examination of McQueen's illustrious career reveals a renewed exploration of class. Operating within a predominantly upper-class profession, he retained his working-class identity while experiencing social mobility. What is particularly compelling about McQueen is his refusal to conform to the conventional expectations of his newfound status; instead, he embraced his background. He cultivated a 'bad boy reputation' (McQueen and I, 2018) within the fashion industry, which was characterized by a striking contrast between his high-fashion creations and his personal attire, often comprising "scruffy jeans and a t-shirt." (McQueen and I, 2018). This contrast illustrates that financial success does not necessarily equate to a transformation of identity. Despite attaining prominence and economic stability, McQueen's persona remained influenced by his working-class origins, challenging traditional notions of class associations with wealth. This is further exemplified by his unwavering support for the renowned working-class model, Kate Moss, during a significant controversy regarding allegations of narcotics use. This incident illustrates that, despite his ascendant social status, he remained committed to advocating for working-class representation and solidarity. His later appearances in "slick suits" (McQueen and I, 2018) and a more polished aesthetic suggest a nuanced relationship with his identity-but anecdotes from his life reinforce the idea that one's foundational class identity persists, regardless of success or financial standing. This exemplifies the complexity of class identity, which transcends mere economic status and is inherently shaped by one's upbringing and experiences.

Chapter 2: 'The Artwork'

What constitutes working-class art? An examination of artworks that reference working-class themes reveals distinguishing elements that categorize them as such. A piece does not need to explicitly label itself as working-class art; it can embody characteristics that resonate with the working-class experience. A pertinent example of this is the British artist Corbin Shaw, whose work intricately navigates themes of masculinity and personal identity across various mediums. Shaw's working-class background is apparent in his artistic expression, as evidenced by his statement, "I didn't grow up with an art background at all - instead of going to galleries, I grew up going to the pub and to the football with my dad." (Shaw, 2020). This statement stresses his rootedness in a working-class milieu, contrasting with the conventional art world, predominantly occupied by middle and upper-class individuals. Shaw's reference to pubs, rather than galleries, highlights the spaces of cultural engagement that are more accessible to those from a working-class background. Furthermore, his upbringing in Sheffield reflects a context that significantly informs his lived experiences and, consequently, his artistic narrative. The way Shaw expresses these experiences reinforces his affiliation with the working class, as both his personal history and artistic vision resonate with the realities of this social strata.

Figure 3 - Corbin Shaw flag 'Never going to be one of the lads'

The exploration of how artistic expressions can implicate the working class without overtly stating it is exemplified in the works of Shaw. Notably, he is recognised for his flag artworks, which frequently incorporate the England flag emblazoned with bold black lettering. One salient piece, titled "I'm never going to be one of the lads," (Shaw, 2020) delves into themes of lad culture and identity, while simultaneously embodying an unmistakable working-class ethos through its design. The language employed in this artwork is particularly engaging, as it invokes the colloquial phrase 'one of the lads', a term deeply rooted in working-class vernacular. This deliberate choice illustrates the thoughtful consideration behind the linguistic elements of his flags, which are crafted to convey multifaceted messages. As Shaw expresses, "I was looking at the language used on football flags, and how working-class men who often don't express themselves emotionally do so in a flag." (Boddington, 2020). This statement highlights the connection between the flag's messaging and issues of masculinity, revealing underlying working-class narratives. Furthermore, the prevalence of football flags in working-class contexts further elucidates the strategic selection of materials, as the artist appears to be directly addressing the demographic with which he is intimately familiar. The England flag, often seen as a working-class emblem, serves as a familiar object frequently displayed in estates and lower-end retail settings that cater to working-class communities. "These are objects chosen for their specific connotations and are inspired by his upbringing in Yorkshire." (Boddington, 2020). This claim reinforces the notion that while the England flag may epitomise a stereotype associated with working-class environments; it also highlights the presence of working-class staples that subtly connote working-class identity without the need for explicit declaration in various artistic works. This clearly illustrates that Shaw is deliberately considering how to convey his message to his audience in a digestible manner. He articulates this intention through the statement, "My flags aim to subtly get my message across by speaking in a recognisable visual language that doesn't alienate its audience"(Shaw, 2019). This emphasises the significance of audience engagement in the creative process and highlights the necessity of accurately targeting one's audience to maximize the impact of a work. Specifically, when addressing a working-class audience, many artists recognise the importance of adapting their work to facilitate engagement. Shaw emphasises the use of visual language and familiar objects as strategies to connect with his audience, thereby employing elements that resonate with their experiences and cultural references.

Clear aesthetics and taste are prominent characteristics in Corbin Shaw's oeuvre, primarily identifiable through his use of bold, black typography in conjunction with recognizable symbols. Shaw articulates that the inspirations behind his work are often rooted in his working-class upbringing, a narrative that is crucial to understanding the development of taste and aesthetic sensibilities. (Shaw, 2020). This idea resonated with Pierre Bourdieu's framework in "La Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste," (Bourdieu, 1984) where he argues that taste and aesthetic preferences - extending beyond art - are deeply shapes by social class and upbringing. (Bourdieu, 1984). Consequently, Shaw's working-class origins likely influence his aesthetic inclinations, which may explain his affinity for incorporating familiar working-class objects and vernacular into his artistic practice. In a complementary discourse, Scott McLaughlan posits that "a person's social class not only predicts but also determines their cultural and social preferences." (Mclaughlan, 2024). This statement aligns closely with Bourdieu's framework but introduces a nuanced consideration regarding the influence of upbringing. It suggests that personal tastes and aesthetic preferences are cultivated from an early age, intricately shaped by one's immediate surroundings. This process often becomes increasingly conscious as individuals mature and engage with their environments. Such a relationship highlights the tendency for individuals from middle- or upper-class backgrounds to be exposed to aesthetically refined, well-designed objects, fostering a bias that favours these representations of beauty (Bourdieu, 1984). Conversely, those hailing from working-class backgrounds may encounter challenges in reconciling with or appreciating these aesthetic values due to limited exposure, leading to a more instinctual or unmediated response to design. Given Shaw's upbringing in a predominantly working-class environment, the interplay of taste and aesthetic becomes crucial in discussions surrounding his work. As a growing artist, it is plausible that we may witness a shift in his aesthetic sensibility, particularly as he navigates new environments beyond Sheffield, where he may increasingly encounter refined aesthetic standards. This potential evolution invites a deeper exploration into how Shaw's artistic trajectory may reflect changes in his socio-cultural context and the broader implications for his work.

Martin Parr is a prominent photographer whose work examines the interplay between taste in design and the sociocultural implications of objects relative to class distinctions. His publication, 'Signs of the Times: A Portrait of the Nation's Tastes' (Parr, 1992), serves as a compelling case study in this investigation, specifically focusing on home décor as a medium through which various class groups express their tastes. Karine Chambefort-Kay, a journalist and scholar, provides a critical analysis of this work and its relation to the class demographics of the period. She claims, "In Signs of the Times, objects are deemed to make statements about people's personalities" (Chambefort-Kay, 2018). This observation highlights how the objects Parr selects reveal significant insights into overall home décor and indicate the socioeconomic status of the homeowners. Parr's imagery highlights the characteristics of working-class households through the lens of objects that are emblematic of their lifestyles, similar to Corbin Shaw's work. This approach demonstrates that the inclusion of specific objects can evoke notions of working-class identity without overtly labelling them as such.

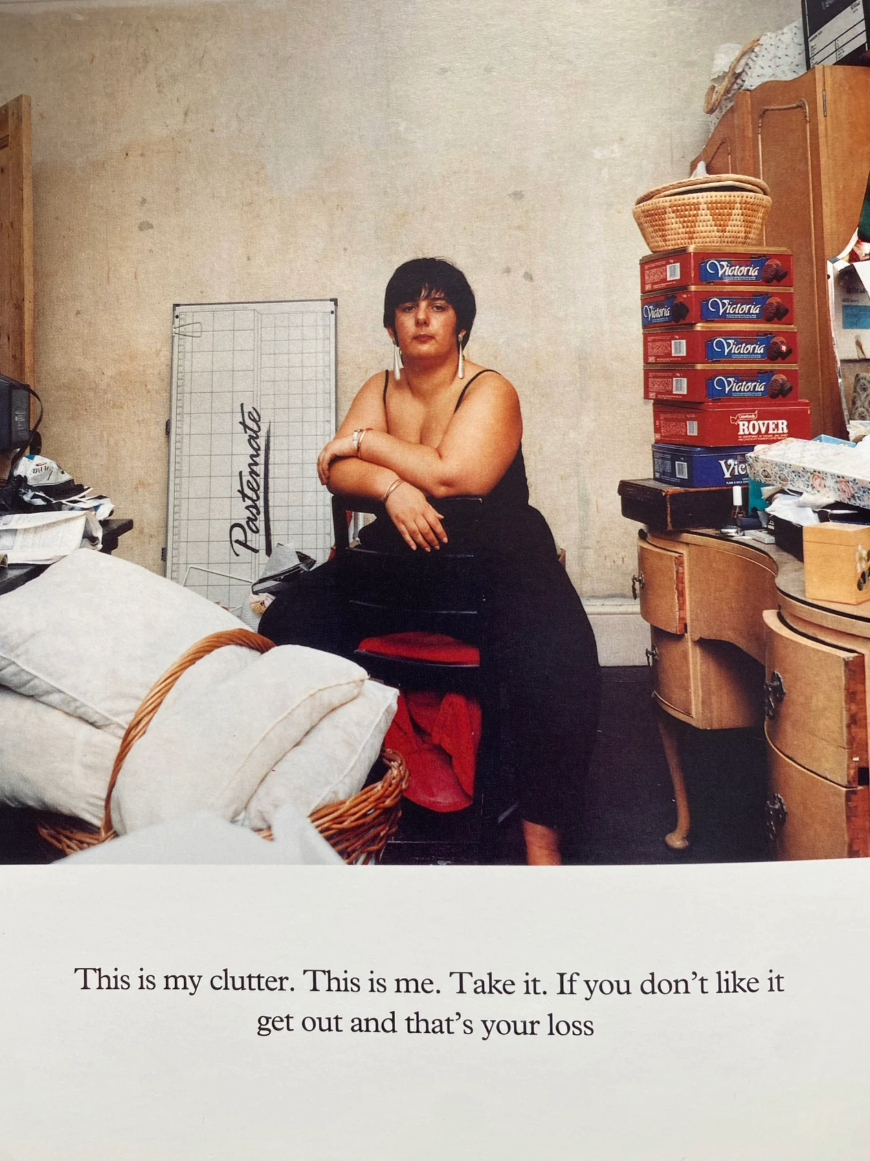

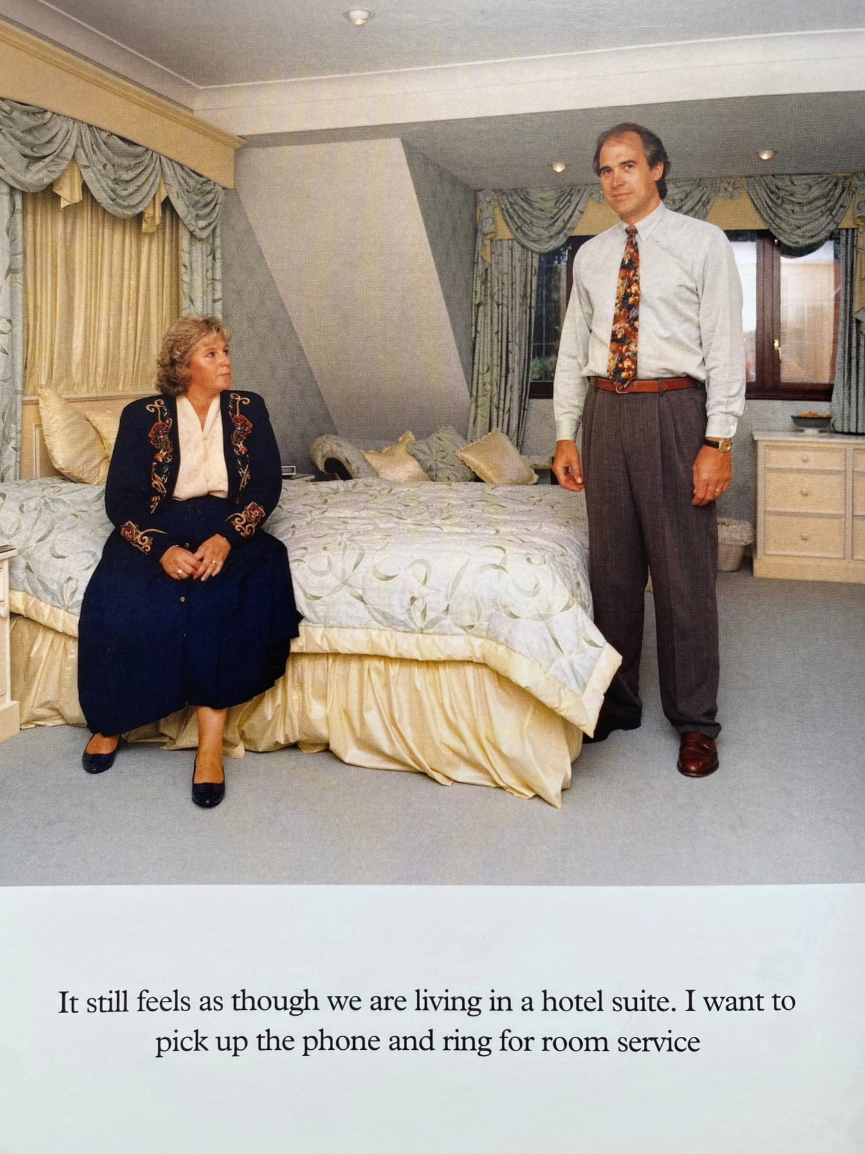

Figures 4 & 5 - Martin Parr 'sign of the times'

A notable example is the photograph displayed in Figure 4 (Parr, 1992). The visual representation of clutter suggests potential hoarding tendencies, a behaviour often stereotypically associated with the working class, who may cling to possessions out of necessity. Furthermore, the distinction between class identities is reinforced not only by the quantity of objects but also by their nature. For instance, the presence of six biscuit tins atop a dressing table hints at a working-class identity, suggesting a comfort with retaining items that others from higher socioeconomic classes may discard in favour of a more minimalist approach. The accompanying text in this image further emphasizes the working-class perspective, stating, "This is my clutter. This is me. Take it. If you don't like it, get out, and that's your loss." (Parr, 1992). This proclamation exudes a sense of empowerment and defiance against social judgment, encapsulating an attitude often found within working-class contexts. The individual depicted in this photograph appears to have reconciled with societal expectations regarding taste and is unapologetically presenting her home as an authentic reflection of her identity. This sentiment aligns with Pierre Bourdieu's theory (Bourdieu, 1984) positing that distinct social classes possess differing tastes informed by their respective social standings. Parr's work therefore illuminates how class identity can manifest through domestic environments without the need for explicit labels.

Throughout 'Signs of the Times', (Parr, 1992) Parr presents an array of examples that explore class taste across a spectrum of socioeconomic backgrounds, reinforcing the notion that the material culture of a home conveys meaning about its inhabitants. The text aptly notes, "In such a frame of mind, home decoration, albeit DIY, was a means to display one's newly achieved social status or a good occasion for conspicuous consumption." (Chambefort-Kay, 2018). Further examination of Parr's oeuvre reveals a conscious effort to highlight the disparities in home aesthetics and tastes, thereby shedding light on the class inequalities that persisted during the Thatcher era. This period was marked by a political narrative asserting the dissolution of class distinctions, yet Parr's photographic exploration serves as a poignant reminder of the social stratifications that continued to influence individual identities and aspirations. However, the work of Martin Parr has faced criticism for allegedly exploiting the individuals he portrays, particularly within the context of his depictions of the working class, which some argue is a product of his middle-class background. This raises an important inquiry: Is it ethically permissible for an individual from a middle-class socioeconomic status to create artwork that represents the experiences of the working class? Ultimately, this question hinges on personal perspectives regarding the ethical implications of Parr's artistic practices and whether one perceives his work as a legitimate representation of the working class or as a form of exploitation.

Chapter 3: 'The Audience'

The direct targeting of working-class individuals can be effectively illustrated through the examination of trade union materials from the era of Margaret Thatcher's governance. To understand the pivotal role that trade unions played within the working class, it is essential to contextualise the socio-political landscape of Thatcher's premiership, during which her administration enacted legislation perceived as antagonistic to unionised labour. Thatcher's policies significantly restricted the power of trade unions (Bond, 2017), and many observers interpreted these measures as deleterious assaults on the working class. As noted by political journalist Owen Jones "the significance of Thatcherism's war on the organized working class [...] was to crush the unions forever." (Jones, 2013). This statement emphasises the targeted nature of Thatcher's approach toward labour organisations, employing tactics aimed at dismantling union solidarity, therefore enabling corporations to exploit their workforce without the protective oversight of collective bargaining. Furthermore, Jones further argues that "Working-class identity itself was under fire," (Jones, 2013) indicating the profound implications of Thatcher's policies on the socio-economic identity of workers across various occupations and trades. This sentiment was echoed by many working-class individuals, who perceived Thatcher's actions as a direct affront to their rights and livelihoods. In stark contrast, members of the middle and upper classes often aligned themselves with her policies, reaping the benefits of an economy that increasingly favoured their interests, thereby exacerbating existing class divisions (Jones, 2013). The significance of trade union activism during this turbulent period cannot be overstated, particularly as it relates to the strikes and collective actions that emerged in response to Thatcher's legislative measures. The printed materials that emerged in support of these strikes serve as crucial artifacts, providing insight into how these movements were a reaction not only to specific policies but also to the broader ideological assault on the working class during Thatcher's administration. These documents offer a critical lens through which to analyse the struggle for labour rights and the persistent quest for working-class dignity in the face of systemic oppression.

The Wapping Dispute, which occurred between 1986 and 1987 in London, centred on the upheavals within the newspaper printing industry. In a decisive and controversial manoeuvre, Rupert Murdoch, the proprietor of four major newspapers, terminated the employment of 6,000 print workers and relocated printing operations from Fleet Street to Wapping, London (Print Subversion in the Wapping Dispute, MayDay). This abrupt dismissal precipitated a strike organised by the affected workers, supported by their trade unions. Although the Wapping Dispute unfolded in the aftermath of the Miners' Strike (Miner's strike, 1984), resulting in its relative obscurity within the broader historical narrative of trade unionism, it produced significant and compelling printed materials that galvanised support for the strikers and encouraged boycotts of The Murdoch owned Sun newspaper. A notable example of such printed material is the satirical publication titled 'The Wapping Post,' which "began circulation on 18 May 1987, and was produced by trade union activists." (Wapping Post, 1986). This newspaper served as a vehicle for disseminating narratives overlooked by mainstream media during the events surrounding the picket lines. Its objective was to engage a wider audience, fostering a deeper understanding of the unfolding realities and inspiring solidarity with the strikers. The Wapping Post achieved this through its innovative design strategy, which cleverly "mirrored the language of tabloid newspapers while subverting conventional hero/villain dynamics" (Wapping Post, 1986). This approach not only resonated with the working-class audience but also addressed their specific informational needs. The medium of a newspaper, familiar to the sacked printers, facilitated the communication of more provocative content and language often restricted in traditional publications. By employing this method, the creators of The Wapping Post ensured that the conveyed information was accessible and relatable, stemming from a shared social context with its readers. Consequently, the linguistic and visual elements of the newspaper reinforced a connection with the audience, allowing for the expression of ideas that might otherwise have been marginalised. This strategic choice emphasises the importance of tailoring medium and design to effectively engage working-class audiences, raising significant questions about the dynamics of representation and communication within social movements.

Figure 6 - The Wapping Post, Volume 2

Another notable group that emerged during the tenure of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was the anarchist collective known as 'Class War,' which was established in 1983. The primary objective of this group was articulated as a desire "to combine politics, class anger, pride, and humour to bring a bit of light relief and get people talking again" (Bigger, 2017). A retrospective examination of the group's actions over the span of more than three decades reveals that their anarchist ideology, political perspectives, and at times violent methods, may be viewed as problematic and not necessarily as an appropriate means of advocating for the working class. Nevertheless, it is imperative to acknowledge the significant impact this group had on the working-class populace, particularly during the 1980s, amidst pivotal events such as the miners' strike and the Wapping dispute-both of which unfolded under Thatcher's political administration.

Founded by Ian Bone, a representative of the working class from South Croydon, along with several others, 'Class War' published a new publication aimed at the working class that sought to undermine traditional political discourse while disseminating anarchist narratives. The publication, titled 'Class War,' adopted the stylistic conventions of a British tabloid newspaper, thereby garnering attention "by parodying the reactionary nature of the British popular press by producing a tabloid style of revolutionary activity" (libcon, 2005). Similar to the Wapping Post, this newspaper embraced a conventional newspaper format, recognising that this medium was familiar to the working class as a means of consuming news. However, 'Class War' distinguished itself from its counterparts in that its imagery, headlines, and narratives were strategically designed to satirize mainstream newspapers, utilising humour as a vehicle to illuminate working-class experiences that were often marginalised in broader media portrayals. The deliberate employment of profanity, stark imagery, and provocative headlines served to engage the working class of that era, leveraging shock value to captivate its audience. At the same time, the dialogue employed was accessible to the working-class demographic, fostering a sense of relatability. The claim that "they invented a new way to sell politics to the working class" (libcon, 2005) resonates with the socio-political climate of the 1980s, as substantial portions of the working class were disillusioned with Thatcher's policies. The newspaper provided a platform for articulating anger and frustration rather than passive acceptance of prevailing political conditions. Given that Thatcher's policies often targeted working-class communities, this publication represented an outlet for the collective outrage that such policies incited.

Evidence of this outrage is particularly evident in an interview that Ian Bone conducted on 'The Jonathan Ross Show,' a popular televised talk show. Bone stated that the newspaper serves to highlight how "the rich, the Tories, and the Labour Party are all against us. We should get up off our knees and fight back against the bastards!" (Bone, 2007). This statement exemplifies Bone's intent to mobilise the public against political adversaries. It is noteworthy that, although Thatcher was not in power at the time of this interview, her policies continued to exert influence into the 2000s. The choice to present an anarchist perspective on a mainstream television platform was unconventional at the time, yet this appearance allowed the public to engage with the raw authenticity of the movement. In this interview, Ian Bone projected an image of the quintessential working-class individual passionate about "wanting the best for working-class people" (Bone, 2007). This representation aimed to resonate with potential new members of the anarchist collective, aligning with the experiences of average working-class individuals rather than the celebrity or upper-class figures who typically frequented such shows. Therefore, 'Class War' not only functioned as a publication but also as a rallying point for class consciousness and activism during a politically tumultuous period in British history.

Figure 7 – Class War Page 3

One of the most striking design elements in the Class War newspaper was the 'Hospitalised Coppers' section, which particularly resonated with its working-class audience. This distinct feature appeared in numerous editions of the publication and aimed to document police injuries sustained during violent demonstrations, such as riots and picket lines, albeit through a satirical and unsympathetic lens. The imagery accompanying the headline suggested a mockery of the injured officers, reflecting the prevailing anti-police sentiments within the readership, which rendered the portrayal both humorous and publishable. In an interview with a university anarchist group, Jon Bigger declares that this section was intentionally positioned "on page 3 to directly mirror the page 3 girls that were seen in the right-wing press" (Bigger, 2020). This design decision is particularly notable as it strategically targeted the working-class audience. The term 'page 3' traditionally refers to a controversial feature in the tabloid newspaper The Sun, owned by Rupert Murdoch, which routinely published large images of topless female glamour models on its third page. By placing the 'Hospitalised Coppers' section in this prominent location, the publication capitalised on the existing familiarity of working-class readers with this page, effectively juxtaposing the portrayal of police with that of the glamour models to create a sense of irony and humour.

While the eventual decline of the Class War newspaper holds significance in the broader narrative of this group, the focus of this analysis is to highlight how the publication's design decisions were explicitly oriented toward the interests and sentiments of the working class, ensuring that their experiences and perspectives were front and centre in its editorial choices.

Conclusion

The inquiry into what constitutes working-class design raises profound questions regarding its categorisation and the complex nature of social class within the field of design. A comprehensive examination of the various components that contribute to working-class design reveals the absence of a singular, definitive answer. This discourse invites scholars and practitioners alike to engage with the complexities surrounding social class in design, advocating for a deeper exploration of these themes rather than retreating from them. The future of the art and design industry necessitates open and inclusive dialogues about class distinctions, as such discussions are integral to dismantling stigmas that hinder the representation of working-class individuals within this elite domain.

It is paramount to recognise that personal interpretations of what constitutes working-class design are subjective, influenced by a plethora of social, economic, and cultural factors. For instance, an artist may not personally identify with a working-class framework, yet that does not diminish the validity of their work as a representation of this social group. This underlines the necessity for a nuanced, case-by-case analysis of artistic contributions, advocating for an in-depth exploration of each work prior to imposing rigid categorisations.

The production of work representative of the working class has experienced a modest resurgence in recent years, attributed to a growing community of individuals who no longer conceal their class status, but rather embrace it in a spirit of authenticity. Central to this evolution is the establishment of initiatives such as 'The Working Class Creative Database' (London, 2020), founded by Seren Metcalfe and Chanelle Love. This initiative aims to foster a community of working-class creatives who come together to share experiences and facilitate conversations about class-related issues. Such groups play a crucial role in the advancement of social class discussions within the arts and design sectors, as they provide essential support mechanisms for working-class individuals through mentorship programs, online discussions, recommended reading lists, and community sessions wherein artists can candidly discuss their creative class identities.

While membership in this community primarily focuses on the individual identity of the artist, it is vital to acknowledge that this represents only one facet of the broader working-class design ecosystem. For the dialogue surrounding social class to extend beyond working-class individuals to wider audiences, other dimensions-such as the nature of the work itself and its audience-must also be considered within the industry. Moving forward, it is imperative to deliberate on all elements that contribute to the definition of working-class work, recognising the intricate complexities at play. By fostering inspiring conversations around these issues, a deeper understanding of social class in design can be cultivated, ultimately enriching the discourse within the field.

Bibliography

Archive: Marx Memorial Library & Workers School (1933), Wapping Dispute material. Available at Marx Memorial Library & Workers School, Farringdon (Accessed: 27/04/2024)

Archive: May Day Rooms (2009), Print Subversion in the Wapping Dispute. Available at: https://exhibitions.maydayrooms.org/wapping/intro/ (Accessed: 01/12/2024)

Ashley, B. (2021). I Never Worried About Being Working Class Until I Went to Art School. [online] Vice. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/working-class-identity-university/ [Accessed 4 Sep. 2024].

Attfield, S. (2016). Rejecting Respectability: On Being Unapologetically Working Class. Journal of Working-Class Studies, [online] 1(1), pp.45-57. Available at: https://workingclassstudiesjournal.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/jwcs-vol-1-issue-1-december-2016-attfield.pdf [Accessed 6 Sep. 2024].

Boddington, Ruby. "The Bayeux Tapestry and Footy Combine to Tackle Men's Mental Health in Corbin Shaw's Work." Www.itsnicethat.com, 6 Mar. 2020, www.itsnicethat.com/articles/corbin-shaw-art-060320.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Chambefort-Kay, Karine. "Martin Parr's Signs of the Times, a Portrait of the Nation's Tastes: Antidote Pictures to Consumerism?" InMedia. The French Journal of Media Studies, vol. 7.1, no. 7.1., 19 Dec. 2018, journals.openedition.org https://doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.1216.

Fox, D. (2016). Know your place. [online] Frieze. Available at: https://www.frieze.com/article/know-your-place [Accessed 4 Sep. 2024].

Gabbott, Miranda. "Trade Union Banners: Kaleidoscopic Symbolism and Strength in Unity | Art UK." Artuk.org, 7 Nov. 2022, artuk.org/discover/stories/trade-union-banners-kaleidoscopic-symbolism-and-strength-in-unity.

Hyuan-joo, Kim, and Kang Hae-Seung. "Archives of Design Research." Aodr.org, 2018, aodr.org/_common/do.php?a=full&b=&bidx=22&aidx=215.

Jackson, J. (2023). The Pride of Working Class Defeatism - Curious - Medium. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/curious/the-pride-of-working-class-defeatism-97804ce25dce [Accessed 30 Jul. 2024].

Jones, Owen. "Class War: Thatcher's Attack on Trade Unions, Industry and Working-Class Identity." Verso, 8 Apr. 2013, www.versobooks.com/en-gb/blogs/news/1274-class-war-thatcher-s-attack-on-trade-unions-industry-and-working-class-identity?srsltid=AfmBOopXYhJz2UT3sMEEAMLHdPhc-4lVA-UNf64ejz4uTtrQEQD61Itx. Accessed 2 Dec. 2024.

Leap (2021). The design industry versus the working classes. [online] Leap. Available at: https://leap.eco/the-design-industry-versus-the-working-classes/.

Mawson, Gaby. "Corbin Shaw - Coeval Magazine." COEVAL, 2020, www.coeval-magazine.com/coeval/corbin-shaw.

Mclaughlan, S. (2024). What Is Pierre Bourdieu's Theory of Taste? [online] TheCollector. Available at: https://www.thecollector.com/what-is-pierre-bourdieus-theory-of-taste/ [Accessed 12 Nov. 2024].

"McQueen and I - Alexander McQueen Documentary." Www.youtube.com, 8 June 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=MrfbKS-p7As.

National Graphical Association. (1986,1987) Picket (43 v). London: National Graphical Association.

Parr, Martin. Signs of the Times : A Portrait of the Nation's Tastes. Manchester, Cornerhouse, 1992.

Riley, D. (2017). SELF-TRANSFORMATION The Appeal & Limitations of the Work of Pierre Bourdieu. [online] Available at: https://sociology.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/faculty/Riley/BourdieuClassTheory.pdf [Accessed 1 Nov. 2024].

Service95.com. (2024). How The Working Class Creative Database Is Opening Doors In The Elite Art World | Service95. [online] Available at: https://www.service95.com/working-class-creative-database\[Accessed 22 Jan. 2025].

Simpson, J.A. (2002). Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

Sloane, M. (2016). Inequality By Design? Why we need to start talking about aesthetics, design and politics. [online] Researching Sociology @ LSE. Available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/researchingsociology/2016/09/12/inequality-by-design-why-we-need-to-start-talking-about-aesthetics-design-and-politics/ [Accessed 7 Nov. 2024].

Small, J. (2010). Working Class Graphic Design. [online] Justin K Small. Available at: https://justinksmall.com/2010/06/01/design-yes-part-iii-working-class-graphic-design/ [Accessed 10 Nov. 2024].

Stevens, M. (2023). Disrupting the Social Class Stigma in London's Top Art Institutions. [online] MADE IN BED Magazine. Available at: https://www.madeinbed.co.uk/features/disrupting-the-social-class-stigma-in-londons-top-art-institutions [Accessed 27 Oct. 2024].

Tetzlaff-Deas, Benedict. "Melting Mettle: A Chat with Corbin Shaw." Now Then Sheffield, 25 Mar. 2020, nowthenmagazine.com/articles/melting-mettle-a-chat-with-corbin-shaw.

Tonti, Lucianne. "The Mind of McQueen: "No Designer I've Ever Worked for Could Think like This."" The Guardian, 9 Dec. 2022, www.theguardian.com/fashion/2022/dec/10/the-mind-of-mcqueen-no-designer-ive-ever-worked-for-could-think-like-this.

Wapping Post. (1986) 'Children used as pickets', Wapping Post (8th Edition), July 26 1986.

"Wapping Post." London Museum, 2024, www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/v/object-790262/wapping-post/. Accessed 3 Dec. 2024.

WCCD. (2020). Home. [online] Available at: https://www.workingclasscreativesdatabase.co.uk/.