Honey Poland 2025

Disposable Trends, Disposable Identity

5867 words | 45mins

Introduction

A person's wardrobe serves as a powerful reflection of their inner identity, acting as an instrument of self-expression whilst mirroring their thoughts and emotions. As fashion critic Dana Thomas once said, "Style is a deeply personal expression of who you are, and every time you dress, you are asserting a part of yourself." The fashion choices we make convey who we are beneath the surface, therefore shaping how others perceive us. Ironically, this goes against the saying "don't judge a book by its cover," as first impressions are heavily influenced by appearance. Our clothing becomes the first thing people notice, making it a crucial tool for both self-expression and external judgement.

This essay will be talking about whether 'microtrends' have harmed an individuals' ability to express themselves as well as hinder identity development. The term "microtrend" is a relatively new label, with it only becoming a 'common' phrase at the start of the twenty first century. According to Trend Bible, a leading trend forecasting agency, a microtrend is "a niche industry specific consumer trend which is mass ready and actionable". It's suggested that "with a shorter life span, microtrends usually filter down from macrotrends and provide opportunities for innovators, designers and marketers to tap into these emerging consumer mindsets". The word was first documented in the early 2000s, with one of its earliest known uses appearing in Simon Reynolds' 2002 New York Times article. In the piece, Reynolds used the term to describe fleeting, niche fashion movements and cultural aesthetics that were emerging rapidly, often driven by internet communities and subcultures, but fading just as quickly, highlighting the increasingly fragmented and accelerated nature of style cycles. Unlike traditional fashion cycles, or 'macrotrends, which previously spanned over decades, microtrends differ in in their scale and longevity. Whilst macrotrends reflect broader, long-term cultural or societal shifts, microtrends are more niche, specific, and shortlived; they often stem from macrotrends and can act as a guide to provide useful insights for companies who are looking to meet the ever-changing demands of a consumer. The growing focus on microtrends correlates with the fast-paced, interconnected society in which niche trends gain popularity and influence individuals quickly, caused by social media and other online platforms.

In the first chapter, I will be looking into the birth of microtrends: how technological advancements such as social media, as well as the rapid manufacturing process which fast fashion adopts, have reduced their lifespans and increased the speed at which they circulate. I will also be analysing how tailored algorithms on platforms such as TikTok and Instagram help accelerate trend adoption and turnover. The idea that brands take advantage of consumers, capitalising off trend cycles through analysing consumer psychology will be explored in this section, helping to explain the phenomenon of impulsive purchasing and a disposable culture. Within the second chapter, the focus shifts towards the psychological aspects of fashion, investigating what influences our fashion, style choices and how clothing serves as a mode of communication, the book 'Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion' by author Charlie Porter will aid me within this research. This chapter highlights the correlation between self-expression and fashion, examining how microtrends diminish individuality and create the psychological pressures to 'fit in'. The commodification of identity arises as an important issue, as fast fashion turns personal style into a product that can be consumed and sold. The third chapter talks about alternative ways to shop, advocating for a shift in consumer mindsets towards sustainable fashion choices and more intention behind purchasing. Emphasising the importance of 'slow fashion', second-hand shopping, and the adoption of minimalist approaches like capsule wardrobes is essential in reducing the amount a consumer buys. By decreasing an individual's screen time and disengaging from the niche tailored algorithms can help create authentic personal styles, that align with their values and resist the fleeting nature of microtrends. Influencers and celebrities are slowly adopting these ideas and are known to have significant power towards what society wears and how they behave, further encouraging a shift towards sustainable fashion choices.

The purpose of this essay is to examine the intricate relationship that exists in the fashion world between psychology, sustainability, and microtrends. By pushing readers to go beyond the rapid demand of trends and towards a deeper connection with their clothes, I hope to show that we can strive in the direction of a more sustainable wardrobe and society.

The Rise of Microtrends and the Cycle of Overconsumption

Microtrends wouldn't be such a polarising trend if it wasn't for the increasing development of fast

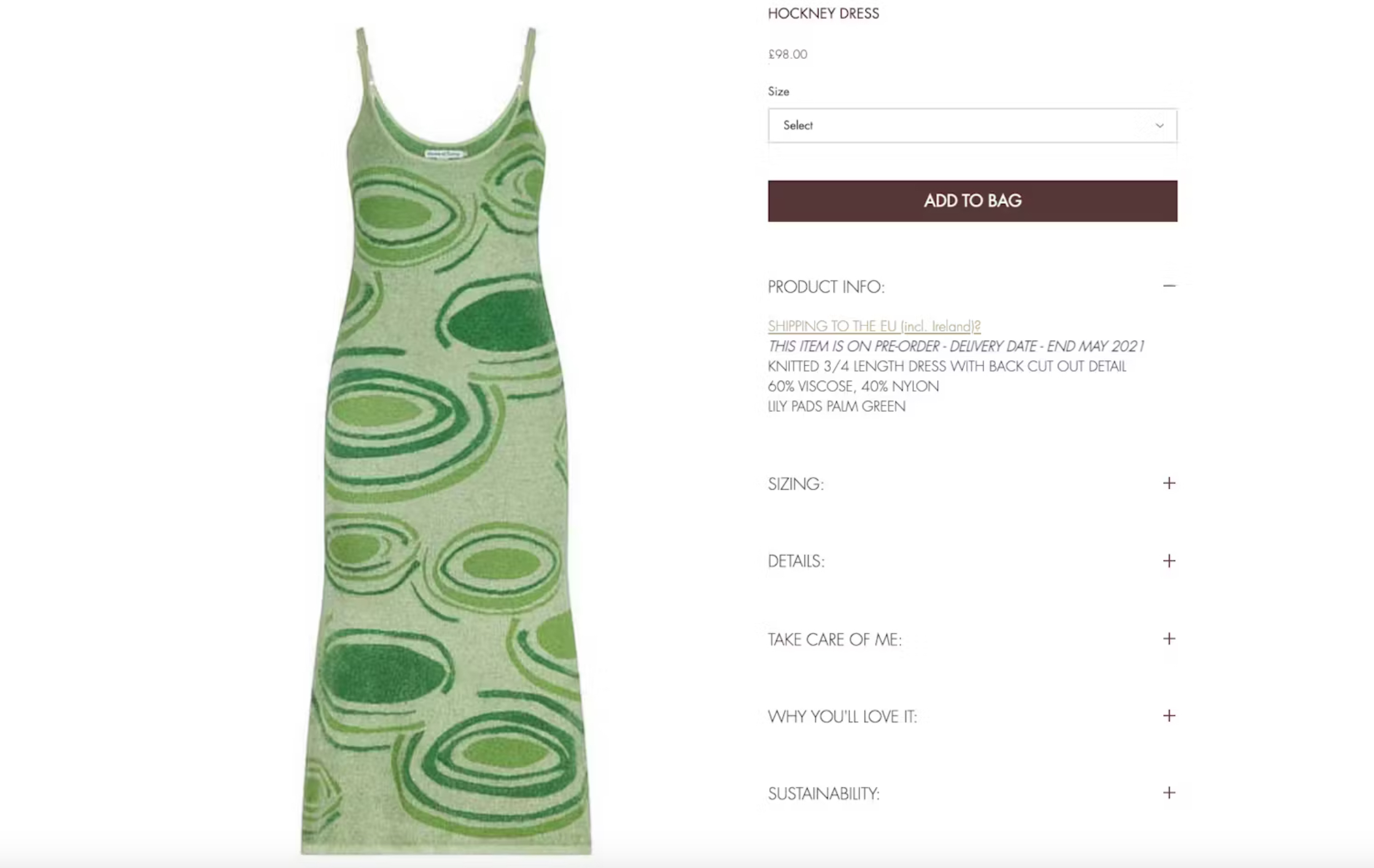

The 'Hockney Dress' from House of Sunny

fashion, a manufacturing process that focuses on producing clothing in mass amounts at a rapid rate. Fast fashion typically uses low-quality materials (such as synthetic textiles) and 'trend replication' in the creation of clothing to provide people with affordable clothes that are accessible to potentially everyone (Stanton, 2024). The clothing industry has experienced a transformation with large companies such as Zara, H&M and Urban outfitters all using this manufacturing process to make their clothing.

Fast fashion accelerates the cycle of what's popular, allowing companies to quickly identify emerging styles and rapidly mass-produce large volumes of clothing. According to journalist Elizabeth Cline, 'Nowadays, fast fashion brands produce about 52 'micro-seasons' a year-or one new "collection" a week,' leading to massive amounts of consumption and waste (Stanton, 2024). Shein adds roughly 6,000 new items to its website every day, giving customers a never-ending supply of new products and the ability to instantly buy the newest clothes at low prices. This rapid production and distribution process promotes impulsive buying without considering sustainability, lifespan, or quality. (Lin, 2022). The disposable nature of these items corresponds to the brief lifespan of microtrends resulting in a vicious cycle of buying, wearing, and disposing that makes the overconsumption problem even worse.

In 2020 - during the COVID pandemic - the fashion world moved online due to the inaccessibility of in-person stores. At the same time, the social media platform TikTok was on the rise with CNBC reporting 2 billion global downloads (Sherman, 2020). As a result of more free time, social isolation and a need for distraction, people spent more time on their phones. With schools, offices, and social events closed, many people turned to their phones to fill the spare time they had, and TikTok's short, captivating videos provided an ideal escape. The personalised algorithm, viral trends, and user-friendly tools made the platform addicting and desirable, therefore people spent many hours of their week scrolling on this app.

Kendall Jenner wearing the 'Hockney Dress' (House of Sunny's Instagram)

As previously mentioned, microtrends have a short lifespan which rapidly gain popularity and fade within weeks and this is especially driven by TikTok's algorithm, which promotes trends or specific items featured in viral videos by influencers and users. One item, which TikTok helped go viral was the 'Hockney Dress' from the small London based brand House of Sunny. In July 2020 the Hockney dress, known for its exclusivity, became highly sought after. Resellers purchased the limited releases and marked them up online, with some listings reaching prices as high as £1,500. Owning the dress was like being part of a "cult", Vogue wrote, ultimately led to it being called "cheugy," a term used to describe something that is outdated or trying too hard to be trendy, predominantly used among Gen Z (Lorenz, 2021). Social media platforms like TikTok have played a huge role in the acceleration of this phenomenon by creating and spreading these trends at an extraordinary rate. The algorithm allows videos to gain millions of views within minutes, distributing content much quicker than traditional older form of media, such as fashion magazines. A typical trend cycle consists of an introduction, rise, recognition, fall, and extinction (Ernest, 2021) - pieces of clothing which once took 20 to 30 years to trend, as seen through physical media, now start and end over the span of just a few months, or even weeks. This rapid trend turnover emphasises the contrast between the slower, curated media of the past and today's fast-paced digital culture.

Brands take advantage of consumer psychology to benefit from the quick trend cycle, encouraging impulsive purchases and promoting a disposable culture. Companies generate a feeling of urgency by responding to emotional triggers such as FOMO (fear of missing out) and the need for approval from others, which encourages customers to purchase products rapidly in order to remain relevant (Bläse, 2023). This is then fuelled by social media platforms and influencer culture, which continuously expose consumers to tailored lifestyles and fresh trends that tell them how to dress to fit in. (Webb,2024). Rapid turnover in styles prevents individuals from developing their own personal sense of fashion and understanding how they genuinely wish to dress. Instead, they are left following the crowd, limiting their ability to express their true identity. By reinforcing these habits, companies promote a disposable culture in which people discard older garments in favour of the latest popular items

The theory of planned obsolescence suggests that products are intentionally made or marketed to have short-term appeal, prompting consumers to buy repeatedly (Bulow, 1986). This concept helps explain how fast fashion brands like Shein and Zara flood the market with affordable, trendy clothing that aligns with fluctuating microtrends, creating a constant need to consume as styles quickly go in and out of fashion. Alongside prioritising accessibility, these businesses also advertise a lifestyle and personality that individuals aspire to. They market their items as symbols of confidence, elegance, or rebellion through campaigns and partnerships with influencers on TikTok and Instagram. Zara, in particular, presents itself as sophisticated and modern, whereas Shein typically associates its clothing with a young and trendy image (Suriarachchi, 2021). By doing this, they influence consumers by suggesting that having certain clothes will allow them to adopt a specific identity or blend in with particular social groups, reinforcing the cycle of planned obsolescence.

As well as overconsumption having an impact on self-image it also comes with serious repercussions on the environment. For these fast fashion brands to keep on top of microtrends, they need to produce immense quantities that ultimately leads to a massive amount of waste and overproduction as many products are discarded soon after being bought and as a result up in landfills. In the book Why Materials Matter: Responsible Design for a Better World by Seetal Solanki, 2008, The Textile Institute in Manchester, estimated that 67 million tonnes of textile fibres were produced globally for human use in 2008 alone and that in 2020, based on current growth rates, this amount is expected to reach 110 million tonnes (Solanki,2008). In 2023, this number increased significantly from previous years, nearly doubling to around 124 million tonnes, which includes all fibres used in clothing, home textiles, footwear, synthetic fibres such as polyester (which dominate the market and are main contributors to this growth) and various other purposes (Textile Exchange, 2024). This demand puts enormous pressure on natural resources, especially water, which is crucial in cotton production. For example, it takes 2,700 litres of water to produce just one cotton t-shirt which is enough to supply one person's drinking water for 900 days. The fashion industry is the second most intensive sector in the world for water-use , utilising around 79 billion cubic meters of water a year (Mogavero, 2020).

The rise of microtrends demonstrates the relationship of social media, consumer behaviour, and fast fashion emphasising the need to change mindsets to be more environmentally and sustainably conscious, especially in today's society, when "climate change is the most serious health threat facing humanity," according to the UN (2022). Understanding the structure and effects of microtrends allows consumers to deeply reflect on their relationship with fashion and choose alternatives that prioritise self-expression.

Why do we Wear What we Wear?

Since ancient times, clothing has been used as a mode of communication, reflecting status, identity, and beliefs. What people wore in Ancient Greece and Rome was tightly correlated to social standing, wealth, and aesthetics. Draped garments like togas and chitons symbolised prestige and power, displaying both the wearer's rank in society and their appreciation for beauty. In the Middle Ages, fashion became deeply intertwined with religion and class. Nobles and members of the upper class dressed themselves in bright, ornately decorated clothing, signalling their wealth and influence. Whereas the lower classes wore much more simple garments in dull tones like browns and greens, reflecting their limited resources and access to vibrant dyes and intricate designs. (Indian Institute of Fashion Technology, 2023). The 17th Century marked a period of extravagance, where lavish and luxurious clothing became a clear indicator of wealth and class. Detailed fabrics, embroidery, and accessories were used to display social status, with fashion acting as a visual representation of one's prosperity.

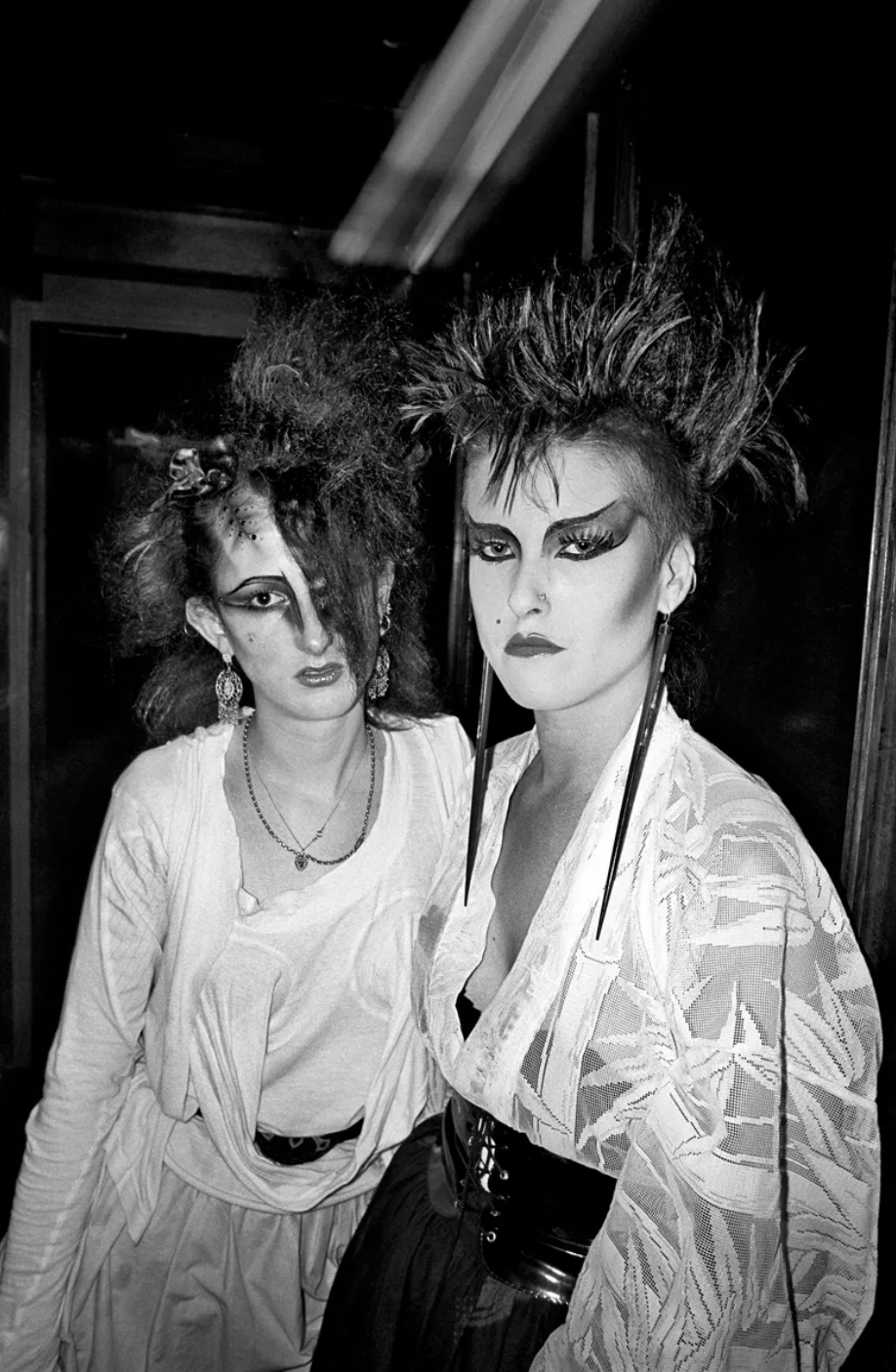

Punks in the 1970s

The 19th Century brought a revolutionary shift with the invention of mass production. The Industrial Revolution made clothing more widely available, allowing people from different backgrounds to access an increased variety of garments. This democratisation of fashion signified the beginning of more diverse personal wardrobes. The 20th Century saw the invention of subcultures like punk, goth, and hippie, and fashion gained new meaning as a form of self-expression and rebellion. Subcultural fashion was greatly influenced by designers such as Vivienne Westwood, especially because of her significant influence on the punk movement. By rejecting social conventions and promoting individualism, Westwood's designs, consisting of ripped shirts, tartan bondage pants and safety pins, transformed apparel into a language of protest. She inspired a generation with her collaboration with Malcolm McLaren and their store SEX, which turned into a centre of rebellion (Bumpus, 2021). Beyond punk, Westwood's theatrical designs and dedication to sustainability pushed the limits of fashion by fusing political activism, avant-garde creativity and connections to history. What makes subcultures different from new trends today is their length and depth of meaning behind them. These groups were usually connected to a certain social or political movement and challenged societal norms while heavily emphasizing the importance of individualism. Bold and unconventional ways to dress became a new form of communication, and their clothes served as a visual metaphor for deeper beliefs, forming a strong sense of self and belonging. Microtrends on the other hand, which dominate the 21st Century, are usually driven by aesthetics and consumer wants rather than cultural or ideological significance. This shift often means that modern clothing frequently lacks the emotional and cultural depth that once characterised subcultural fashions, reducing fashion to fleeting, surface-level expressions rather than meaningful acts of communication

In Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion, Charlie Porter explores how members of the Bloomsbury Group, a group of early twentieth-century artists and thinkers who were well known for going against conventional norms,used clothing as a means of artistic, intellectual, and sexual liberation. He investigates the restrictions and possibilities of fashion through the lens of various members, such as E.M. Forster's top buttons symbolizing repression and Vanessa Bell's wayward hems representing creativity. Porter also delves into Virginia Woolf's choice of orange stockings, highlighting her self-consciousness and individuality. He suggests that clothing can be a tool for patriarchal control or a means of liberation, depending on how it is worn and perceived and with these historical perspectives they can highlight the importance of clothing as a means for storytelling and cultural expression, in addition to its practicality. As the Bloomsbury Group proved, what we dress can tell a lot about who we are, what we think, and how we position ourselves within society.

Fashion has evolved drastically over time with the clothes mirroring our personality, values, and even our mood. Although the ability to express ourselves can come with some constraints, with societal and economic pressures controlling what people feel comfortable wearing. For example, workplaces dress codes can hinder people's creativity, reinforcing professional norms that typically favour neutral colours and simple structured silhouettes over bold personal choices. Cultural expectations also play a part, with events like weddings and religious ceremonies often coming with strict dress codes as well as certain religious traditions which encourage a more modest and conservative approach to fashion, prioritising function over form. Social media plays a vital role in the way we interact with fashion nowadays. TikTok and Instagram continuously redefine what is 'in' pressuring people to follow these constantly shifting trends instead of encouraging creative freedom in fashion choices. Klepp and Storm-Mathisen, in their book Symbolism in Dress and Appearance: Individualism and Collectivism in Modern Culture, argue that this tension between self-expression and societal influence is the core of modern fashion. While clothing can be freeing, it can also confine people in cycles of conformity and validation from others. For many, constructing an outfit can be similar to building an artistic portfolio as it combines personal style with cultural influence. For instance, the growing demand for and production of more gender-neutral clothing, damages conventional views of masculinity and femininity, enabling people to discover themselves more freely without labels or judgement. Fashion can be very intimate while also facilitating connections with wider communities. Ultimately, fashion is one of the most accessible and inventive ways to present oneself and despite the need to conform to these trends and cultural expectations, it makes it possible for people to make statements, tell their stories, and challenge boundaries. Fashion, either through bold choices or modest minimalism, is an instrument of navigating identity in a world where individual and cultural influences are always changing.

Fast fashion has changed the historical relationship between clothing and self-expression. As brands are so focused on prioritising rapid mass production of trends and capitalising on it, it means there's limited space for creativity; and with the extreme speed these trends cycle restricts individuals' opportunity to properly experiment with their own unique personal style and find clothes that reflect who they really are. People constantly feel the need to update their wardrobe to stay relevant which puts fashion as more of a transactional process instead of a meaningful form of self-expression. Although the disposable nature of fast fashion is being challenged by alternative movements like slow fashion and shopping second hand, which ultimately help protect the history of fashion as a form of expression. These alternatives attempt to restore fashion's function as a platform for identity and narrative, pushing customers to value uniqueness, sustainability, and quality over fads.

This issue reflects a deeper alienation within consumer culture as Barbara Vinken (2005) writes in Fashion Zeitgeist "Glittering and blinding, fashion draws attention away from the substance of things. It is the very personification of the individual alienated in the rush of consumption, of the self lost in the world of commodities" (p.21). This quote implies that fashion, with its dazzling and eye-catching nature, distracts people from the deeper more important aspects of life. It portrays clothes as a symbol of alienation, where individuals lose their sense of true self as we are all so heavily lost in the world of consumerism and obsess over our appearance and how we look, that we forget how fashion is so much more than just looking pretty. The quote critiques the system that microtrends belong to, one that encourages rapid consumption and a lack of depth. People rejecting microtrends may be seeking to break free from this alienation, instead focusing on sustainable, slow fashion or timeless, meaningful style that reflects their true identity rather than conforming to a commodified version of self-expression. In addition, fast fashion's speed and accessibility drives this impulse buying and a throwaway mindset, therefore making it hard for customers to build an actual relationship with their items. Instead of building pieces that mirror their personalities, consumers are trapped in a cycle of overconsumption, this behaviour can be comparable to that of a child captivated by a shiny new toy. Just as a child quickly abandons an old toy in favour of something new and exciting, consumers move on quickly from items they've worn once or twice before throwing it away and buying the newest freshest trends.

Resistance and Reclaiming Authenticity

Individuals and communities have begun to push back against the dominance of microtrends and are trying to develop and reclaim a more authentic sense of self. In this chapter I will be examining counter-movements and alternative approaches to style and identity, exploring the different ways people are navigating and resisting the pressure to conform to these fleeting trends.

In a response to the growing environmental and social effects caused by fast fashion, the slow fashion movement has grown massively in popularity in recent years. In the book "Slow Fashion: Aesthetics Meets Ethics," author Safia Minney describes slow fashion as an approach that "identifies sustainable fashion solutions, based on the repositioning of strategies of design, production, consumption, use, and reuse, which are emerging alongside the global fashion system, and are posing a potential challenge to it." The Slow fashion movement urges people to be conscious of their clothing choices by prioritising sustainability, ethical production, and longevity, encouraging consumers to invest in timeless durable pieces rather than following seasonal or microtrends. Brands such as Patagonia promote customers to repair and reuse their clothing through schemes such as the Worn Wear program, which extends the lifespan of each piece of clothing while also limiting wasted materials. Patagonia's aim is to reduce its environmental footprint by encouraging a culture of thoughtful consumption and inspiring other people to do so as well (Zuno Carbon, 2024). Often these companies will produce small batch items, resulting in garments that are less likely to be seen, allowing room to express personal style without feeling as if they're just following large trends. As slow fashion prioritises long lasting pieces, it enables people to put more thought in before investing and purchasing items that align with their personality, rather than just following what the Kendall Jenner's of the world are wearing. Clothing that lines up with someone's true style can, over time, becomean expression of their character.

Promoting slow and sustainable fashion doesn't just stop with brands, influencers such as Emma Chamberlain, a prominent Gen Z influencer and entrepreneur well known for her relatable and candid personality, has significantly impacted fashion trends. Her content is heavily fashion orientated, showing thrift hauls, lookbooks and fashion week vlogs, as well as collaborations with luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton and Cartier (Sherbert, 2024).Emma has a distinctive style, which combines vintage, casual, and high-fashion pieces with her candid personality, inspiring viewers to embrace shopping second hand and encourage self-expression through fashion. It appears that Emma Chamberlain is done dressing for the algorithm since in her most recent video, she clears 95% of her wardrobe to leave only a few classic, timeless pieces (Fernandez, 2024). She mentions that "part of the reason why I ended up with such a ridiculous amount of clothing was because I wanted to keep up with the internet closet". As Emma is such a big influencer, the power to reshape how her large audience views fashion, pushing the idea of quality over quantity. By openly discussing how the desire to "keep up with the internet closet" led to overconsuming, she sets an example, and her influence has the possibility to make slow fashion more mainstream and inspire more purpose and authenticity behind buying.

Capsule wardrobe

Another alternative approach to the overconsumption of fast fashion is minimalism; a lifestyle idea that concentrates on having fewer but higher-quality items and is a key part of the increasing sustainability movement. Minimalism, which is typically associated with the motto "less is more," pushes people to simplify their lives and practise mindful buying. The founders of The Minimalists, Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, define it "a tool to rid yourself of life's excess in favour of focussing on what's important-so you can find happiness, fulfilment, and freedom" (Millburn & Nicodemus, 2011). Regarding the fashion world, this means building interchangeable outfits with only a handful of timeless, high-quality pieces also known as a capsule wardrobe. The benefit of a capsule wardrobe is that with these classic garments you are less likely to hate them as they can never go out of fashion. The adoption of a simplified closet is an example of a wider cultural change that prioritises making well educated choices over overconsumption and with this concept it can further help you to develop your own distinct tastes, without having a large stack of fast fashion microtrends sitting in your cupboard.

Adopting a completely slow fashion wardrobe can have its difficulties due to its higher costs and the structural issues within the fashion industry. Slow fashion prioritises ethical labour, using sustainable materials, and high-quality outcomes, making items more expensive than fast fashion alternatives. For many, the upfront cost of slow fashion is too expensive, despite its long-term quality and durability. Additionally, the convenience and accessibility of fast fashion brands, along with the constant trends, make it difficult for consumers to resist cheaper, more convenient options. Building a slow fashion wardrobe also requires a mindset shift towards valuing fewer, higher-quality pieces and rejecting the constant demand for new trends, which can be a struggle in a consumer-driven culture. Especially In 2025, with the rise of inflation, the cost-of-living crisis and limited disposable income, sustainable clothing is not the priority for a large majority rather meeting basic needs like paying rent and putting food on the table is at the forefront of many minds. The transition to slow fashion can feel unattainable, emphasising the need for systemic change to make sustainable clothing more accessible and affordable.

Thrifting has become an increasingly popular and effective alternative way to sustainably build your wardrobe. By shopping second hand, consumers take part in the circular economy where clothes are reused rather than thrown away, minimising waste and extending the lifespan of garments, which is especially important in combatting the rising problem of textile waste as these microtrends result in millions of tonnes of scraps thrown away every year (Hill, 2024). The 21st century and the technological advancements has changed how we second-hand shop making the experience easier and more accessible. Platforms like Depop and Vinted allow people to sell their clothes they no longer want and give them a new home. Depop is especially popular among young people as the app is like an Instagram for second hand shopping, with features like following other sellers, liking items and private messages making it an engaging way to shop second-hand. Used clothing is often a fraction of the price compared to new designer pieces - it is a cheap way to get unique, long-lasting clothing without the high prices of many sustainable brands. Second hand stores frequently stock unique things that are no longer available in mainstream retailers and vintage pieces, for example, can help wearers stand out while also creating a more personalised, expressive wardrobe. These things frequently have a history, bringing character and emotional worth to wardrobe options.

Personalisation has become a popular modern way to express individuality while also being sustainable and saving money. In 2024, a new trend emerged called 'Jane Birkening' your bag. This concept, inspired by the well-known 60s fashion icon Jane Birkin, involved taking a bag and decorating it with personalised items to make it unique (Phelps, 2024). Rather than keeping her bags pristine and simple, Birkin embraced the signs of use and ownership, by styling her bags with badges, stickers, keychains, and ribbons. She also embraced imperfections like scuff marks, acknowledging the fact that the bag had lived a life with its owner.

Jane Birken with her bag

Patches and badges on hats and clothes have become a popular accessory in recent years and with this increasing focus on personalisation, allows people to feel a sense of individuality in their fashion choices. The appeal of personalisation lies in its ability to create statement pieces that reflect individual style while at the same time remaining versatile. Items that can be customised or accessorised like bags or jackets can offer endless possibilities for new looks without encouraging overconsumption. By mixing and matching details, individuals can create a wide variety of outfits, embracing creativity while reducing the need for excessive purchases.

Another way to target this issue is by looking at it from a different angle, promoting a detox from social media and minimise screentime, would help combat this problem. Microtrends are constantly being pushed by niche tailored algorithms, pressuring people to conform to what 'TikTok' deems fashionable. This leads to a vicious cycle in which one's personal style is determined by current trends instead of their authentic preferences (Fernandez, 2024). People can figure out their own tastes as well as way of life that is more in line with who they really are by removing themselves from this endless overload.

The popularity of "anti-trend" aesthetics is frequently exploited by social media, fashion influencers, and marketers, who transform them into another fad rather than a genuine critique of the status quo. This begs the question of whether trends can actually be avoided or if these movements will always become a part of the cycle they are trying to break (Kawamura, 2020). In recent years, movements and groups have emerged that encourage individuals to find their own style, rather than simply following what's popular at the moment. While it's perfectly fine to appreciate certain trends, the emphasis is on understanding what you genuinely enjoy wearing, rather than succumbing to the pressure of what everyone else is wearing. One such example is the "normcore" aesthetic, which embraces a rejection of the trend cycle through an anti-fashion approach. Normcore prioritizes neutral, practical, and comfortable clothing that does not adhere to conventional fashion standards (Steele, 2019). It's a celebration of simplicity and individuality, where personal expression is rooted in timeless pieces and functional styles rather than constantly chasing the latest microtrend. This shift encourages people to step away from the fast-paced trend cycle and embrace a style that is more reflective of who they are, promoting a deeper sense of self-expression and identity beyond the influence of digital trends.

Conclusion

To conclude, this essay has delved into the harmful consequences of microtrends as a societal issue, with the focus of this study showcasing it as the driving factor into how many view their self-expression and identity. The cultural, social, and economic factors involved within microtrends has shaped the fashion world, ultimately damaging how people treat the environment, as well as their individual personal style. Fashion has traditionally been recognised and praised for its ability to present a person's uniqueness and character, but with the ever-growing pressures of consumer capitalism as well as society's has destroyed people's distinctive personality, led to the invention of 'TikTok fashion'. Even as societal structures shifted with help from events like the Industrial Revolution, fashion adapted to reflect new realities, such as the democratisation of clothing and the rise of self-expression through subcultures in the twentieth century. From social subgroups such as the punk and goth scene which are iconic for their bold political statements, rebellion, and fashion choice, clothing and design has always been a powerful tool for communicating who we are, where we all originate from and the significance of this. Microtrends, by their nature are fleeting; styles arise through rapid popularity, at an equivalent rate to how fast they go out of fashion. Famous fast fashion brands like, Zara, H&M and Shein exploit this cycle, producing affordable, trend-driven garments at an extraordinary speed. Whilst these brands provide affordable pieces, democratising trend accessibility, fast fashion perpetuates overconsumption resulting in environmental harm and prioritises profit over sustainability. The disposable nature of these trending items creates a 'purchase, wear, discard' cycle, aligning with the brief nature of microtrends.

Studying the algorithmic structure and how specific trends are prioritised to generate engagement was essential in establishing its rapid adoption. Influencers positioning these trends as gateways to social acceptance or status, is overall harmful for encouraging this participation, which is driven by the 'all consuming' fear of missing out (FOMO). However, this often comes at the expense of individuality, as consumers adopt their homogenised aesthetics instead of their own cultivating personal styles. Consumer culture is a critical component of this discussion. Fast fashion brands market clothing not just as garments but as symbols of lifestyle, belonging, and success. By commodifying identity, they manipulate consumers into chasing unattainable ideals, fostering dissatisfaction and impulse buying. This transactional approach to self-expression, where trends replace creativity, often leaves individuals disconnected from their sense of style. As highlighted in Charlie Porter's Bring No Clothes, members of the Bloomsbury Group used fashion to challenge societal norms, demonstrating how clothing can reflect deeper ideologies. Nonetheless, the rise of slow fashion provides hope for a more meaningful relationship with clothing. The slow fashion movement has promoted mindfulness in consumption, urging individuals to prioritize quality, longevity, and sustainability. As Safia Minney notes in Slow Fashion: Aesthetics Meets Ethics, slow fashion challenges the "throwaway culture" of fast fashion by fostering a deeper connection between people and their garments. This shift not only benefits the environment but also encourages consumers to reclaim their identities through thoughtful choices.

To combat this issue, second-hand shopping has gained popularity and should stay this way as its sustainable and creative nature makes for an effective alternative to fast fashion. Platforms like Depop and Vinted make thrifting or second-hand shopping more accessible, allowing for consumers to participate in the circular economy, building wardrobes that are both unique and environmentally friendly. Vintage and pre-loved clothing is powerful in curbing the fast fashion cycle, this is through original pieces carrying a sense of history a nd individuality, enabling wearers to craft expressive, personalized styles that stand out from mass-produced trends. Personalisation and DIY fashion, such as 'Jane Birkening' bags or adding patches and badges to garments, further empowers individuals to reclaim their creative agency in fashion, turning everyday items into meaningful one-of-a-kind pieces. Brands like Patagonia and influencers such as Emma Chamberlain have championed this movement, promoting thoughtful consumption and the idea that fashion can be both expressive and sustainable. Chamberlain's candid discussions about overconsumption, and her shift toward a minimalist wardrobe, have inspired her audience to embrace quality over quantity. This mindset can help redefine what it means to be stylish in a world dominated by fast trends. Despite these promising alternatives, systemic barriers such as the high cost of sustainable clothing and the pervasive influence of social media, microtrends continue to challenge the transition away from fast fashion. The convenience and affordability of fast fashion, combined with the pressures of inflation and the cost-of-living crisis, make it difficult for many to prioritise sustainability. Additionally, the algorithms driving social media platforms often reinforce the cycle of these fads, pushing individuals to conform to ever-changing definitions of what is "in." However, emerging movements like normcore and anti-trend aesthetics offer hope to this by rejecting the trend cycle altogether. These approaches celebrate simplicity, practicality, and timelessness, encouraging individuals to prioritise authenticity and self-expression over fast paced styles. Ultimately fashion remains one of the most accessible and inventive way to navigate identity in a rapidly changing world, therefore more research needs to be done to help preserve individuality with the world of fashion.

Bibliography

Beswick, C. (2024). 'Examining the era of micro trends'. Global Fashion Agenda. Available at: https://globalfashionagenda.org/news-article/examining-the-era-of-micro-trends/ (Accessed: 11 November 2024).

Bläse, R., Filser, M., Kraus, S., Puumalainen, K. and Moog, P. (2023). Non-sustainable buying behaviour: How the fear of missing out drives purchase intentions in the fast fashion industry. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372406242_Non-sustainable_buying_behavior_How_the_fear_of_missing_out_drives_purchase_intentions_in_the_fast_fashion_industry (Accessed: 13 December 2024).

Bumpus, J. (2021) Vivienne Westwood: The Story Behind the Style. London: White Lion Publishing.

Eggertsen, L. (2019). 'The Slow-Fashion Shopping Guide: 23 Brands That Put the Planet First', Who What Wear, 14 August. Available at: https://www.whowhatwear.com/slow-fashion-brands (Accessed: 12 January 2025).

Bulow, J.I., 1986. An Economic Theory of Planned Obsolescence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 101(4), pp.729-749. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884175

Ernest, M. (2021). 'TikTok, House of Sunny's Hockney Dress, and the green trend fast fashion drama', Input, 3 June. Available at: https://www.inverse.com/input/style/tiktok-house-of-sunnys-hockney-dress-green-trend-fast-fashion-drama (Accessed: 20 November 2024).

Fernandez, C. (2024). 'Why Emma Chamberlain Cleaned Out Her Closet', The Cut, 10 December. Available at: https://www.thecut.com/article/why-emma-chamberlain-cleaned-out-her-closet.html (Accessed: 12 January 2025).

Hill, M. (2024). 'What is Circular Fashion?', Good On You, 1 May. Available at: https://goodonyou.eco/what-is-circular-fashion/ (Accessed: 10 January 2025).

Minney, S., 2016. Slow Fashion: Aesthetics Meets Ethics. Oxford: New Internationalist Publications Limited.

IIFT Bangalore. (n.d.). 'The art of self-expression: How fashion can speak volumes about you'. IIFT Bangalore. Available at: https://www.iiftbangalore.com/blog/the-art-of-self-expression-how-fashion-can-speak-volumes-about-you/ (Accessed: 11 November 2024).

Kawamura, Y. (2020). Fashion-ology: An Introduction to Fashion Studies. Bloomsbury.

Klepp, I. G., & Storm-Mathisen, A. (2005). Symbolism in Dress and Appearance: Individualism and Collectivism in Modern Culture. Scandinavian Journal of Consumer Research.

Knight, I. (2024) Old things. Substack. Available at: https://indiaknight.substack.com/p/old-things (Accessed: 2 January 2025).

Lee, A. Y. (2022). 'Microtrends: The implications of what you see on your "For You" page'. The Harvard Crimson. Available at: https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2022/2/18/microtends-fashion-think-piece-tiktok/ (Accessed: 7 December 2024).

Lorenz, T. (2021). 'What is "cheugy"? You know it when you see it', The New York Times, 29 April. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/29/style/cheugy.html (Accessed: 16 November 2024).

Millburn, J.F. and Nicodemus, R. (2011). Minimalism: Live a Meaningful Life. Asymmetrical Press.

Mogavero, T. (2020). 'Clothed in Conservation: Fashion & Water', Sustainable Campus, 16 April. Available at: https://sustainablecampus.fsu.edu/blog/clothed-conservation-fashion-water (Accessed: 10 January 2025).

Phelps, N. (2024). 'Jane Birkinifying' is the bag trend that actually makes sense. Vogue. Available at: https://www.vogue.com/article/jane-birkinifying-bag-trend (Accessed: 15 January 2025).

Reynolds, S. (2002). 'The 70's Are So 90's. The 80's Are the Thing Now', The New York Times, 5 May. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com (Accessed: 11 November 2024).

Rogers, L.G. (2021). 'TikTok teens: Turbulent identities for turbulent times', Film, Fashion & Consumption, 10(2), pp. 377-400. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1386/ffc_00031_1 (Accessed: 28 November 2024).

Sherman, A. (2020). 'TikTok reveals U.S., global user growth numbers for first time'. CNBC, 24 August. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/24/tiktok-reveals-us-global-user-growth-numbers-for-first-time.html (Accessed: 10 December 2024).

Solanki, S. (2018). Why Materials Matter: Responsible Design for a Better World. London: Prestel.

Suriarachchi, M. (2021). 'Micro-trends and Overconsumption: Fashion Consumerism in the 21st Century', CAINZ, 24 August. Available at: https://cainz.org/10066/ (Accessed 10 December 2024).

Steele, V. (2019). 'Normcore and the New Anti-Fashion Movement', Fashion Theory, 23(4), pp. 563-582.

Stanton, A. (2024). 'What is fast fashion, anyway?', The Good Trade. Available at: https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/what-is-fast-fashion/ (Accessed: 29 December 2024).

Vinken, B. (2004). Fashion Zeitgeist: Trends and Cycles in the Fashion System. 1st ed. London: Berg.

Webb, B. (2024). 'Overconsumption: Can we ever put the genie back in the bottle?', Vogue Business, 29 August. Available at: https://www.voguebusiness.com/story/sustainability/overconsumption-can-we-ever-put-the-genie-back-in-the-bottle/ (Accessed: 10 January 2024).

Wolfe, I. (2023). 'These 17 Slow Fashion Brands Will Help You Ditch Fast Fashion', Good On You, 23 October. Available at: https://goodonyou.eco/slow-fashion-brands/ (Accessed: 6 January 2024).

Zuno Carbon. (2024). 'Lessons from Patagonia's Sustainable Supply Chain', Zuno Carbon, 18 April. Available at: https://www.zunocarbon.com/blog/patagonia-supply-chain (Accessed: 15 January 2024).