INTRODUCTION

Music, music videos, imagery and television play a pivotal role in the messages individuals hear and see. These messages can be positive or negative, and they can influence how consumers and producers respond to and interrogate them critically, socially, physically, and emotionally (LaVoulle, C. & Lewis Ellison, T. 2017. pp 7). The purpose of this study is to research and identify the cultural significance of the media in representing the black body, and specifically black hair, throughout the 1990s to the present. With a better knowledge of the traditions and history of the black aesthetic will come a greater appreciation and understanding of the significance it holds within the black community. The intention is to gain a deeper comprehension of how black identities are portrayed through artistic expression, and the use of the media in communicate these identities.

Hair shapes the black identity; its a symbol of black heritage and a reminder of black ancestral history. However, with this history comes deeply-engrained systemic racism that has lead to micro-aggressions, cultural appropriationand the belief that European physical attributes have been and continue to be the ultimate definition of beauty in mainstream society. This beauty standard exemplifies the attitude that the more closely associated an individual is with European features, the more attractive they are considered; those standards correlating to whiteness (figs. 1 & 2). Thse standards include lighter skin, straight hair, a thin nose and lips, and light coloured eyes (Bryant, S. 2013). Figure 1 shows a woman with European features, which can be compared compared to Figure 2 which shows a black woman's common features. To many the comparisons are slim, however, the beauty standards set within society place both these women within a hierarchy of attractiveness. A strong distinction between the two women is how they choose to style their hair, and accompanying this comparison of the aesthetic value and binary of 'beautiful/ugly' is a racist rhetoric that separates their human worth. This unconscious bias has created a continuous battleground for black people and their natural hair; a love/hate relationship, a constant need to alter and change their identity.

With the rising 'Natural Black Hair Movement' and popular culture now embracing black hair in television, music videos, and photography, we finally see empowerment and representation for black people. This article asks: emerging from the struggle of where black people came from, will the 21st century see true acceptance for natural black hair? How does the portrayal of black hair in the context of the black body, as seen through music, television and the media, represent black identity?

To fully understand the significance of hair in today's black community, we need to first look to the past.

Figure 1: Widny Bazile by Aris Jerome, 2017

Figure 1: Widny Bazile by Aris Jerome, 2017

Figure 2: Naomi Watts, Vogue. 2014

Figure 2: Naomi Watts, Vogue. 2014

BLACK HAIR: HISTORY AND TRADITIONS

In many African countries, hair and braids would signify someone's standing, including their rank within society, their religion, as well as their marital status (and more). Beyond this, hair would communicate their identity. Hair was also thought to hold spiritual importance and contain immense power. It was believed that gods and spirits could reach the soul through the hair (Alexander, M. N/A). Braiding was and still is an art form, often taught by the most senior female members within the family and the community.

Yoruba refers to the West African ethnic group of that name, as well as to its language and religious philosophy. In the Yoruba tradition, all women were taught how to braid hair and any young girl that showed talent in hairdressing would then become the "master", taking responsibility for the entire community's coiffures. Before a "master" died she would pass down her toolbox to a successor within the family, during a sacred ceremony (D, Byrd & L, Tharps, 2001. pp 4-7). Today, people of Yoruba descent make up one of the largest populations on the African continent. Even under the Spanish colonial rule the Yoruba tradition never died - they merely transformed. "Lucumí" was the new name given, in order to disguise the Yoruba under colonial rule. The Spanish mocked this so-called "worship of saints", with a title more familiar to those outside of the religion: Santería. Santería travelled the world, and is still practiced in Cuba, across Central America and the Caribbean, as well as the United States (Chisolm, K. 2018). Santería was conceived as a discreet way to keep Yoruba traditions alive, and today it is still talked about openly. Popular New York City-based rapper Princess Nokia released a single in 2017 called "Brujas" which details her relationship with ancestral magic, the songs music video integrating symbolism and rituals from Santería, such as hairstyling and chanting (see figs. 3 & 4). From these images it is clear that hairstyling was, and still is, an intimate and personal art practice that holds great importance within the black community.

Despite the significance hair braiding had for millions of African people, slavery allowed white slave owners to oppress black people even further. Constantly reminded of their "ugliness" and "inferiority" to white people, the black slaves began to believe the racist words of the oppressor. Joy DeGruy Leary, a mental health therapist and doctoral candidate studied the intergenerational trauma African-Americans suffered because of slavery. She explains how slave-owners demoralised and brainwashed the slaves into believing they were unattractive and lesser than white citizens. When the slave women internalised the racist language, which was almost inevitable, it wasn't long before they passed this pathology on to their sons, daughters and generations to follow, (D, Byrd & L, Tharps, 2001). This racist presence is still within the psyche of many black individuals, and the trauma is still transmitted through their bloodlines. Due to this damage, many black individuals and other minorities alter their outward expression to successfully navigate interracial interactions, this is known as code switching. It has large implications for the well-being, economic advancement and even physical survival of black people. Code-switching often involves adjusting ones style of speech, appearance, behaviour, and expression in ways that will optimise the comfort of others in exchange for fair treatment, quality service, and employment opportunities (McCluney, C. & Robotham, K. & Lee, S. & Smith, R. & Durkee, M. 2019). Offered as a defence against linguistic discrimination, systemic racism and injustice, code-switching is a survival trait that many black people and other minorities have learnt through history for self-protection. In the search for acceptance, code-switching can offer opportunities often denied to black people. Comedian Dave Chappelle - who incorporates a satirical white voice into his standup routines - once said, "every black American is bilingual. All of us. We speak street vernacular, and we speak job interview." (McWilliams, A. 2018).It could be seen that altering one's appearance is the kind of visual code-switching seen as necessary in order to be accepted within the racist hegemonic system.

Figure 3: Princess Nokia, Brujas Music Video, 2016

Figure 3: Princess Nokia, Brujas Music Video, 2016

Figure 4: Princess Nokia, Brujas Music Video, 2016

Figure 4: Princess Nokia, Brujas Music Video, 2016

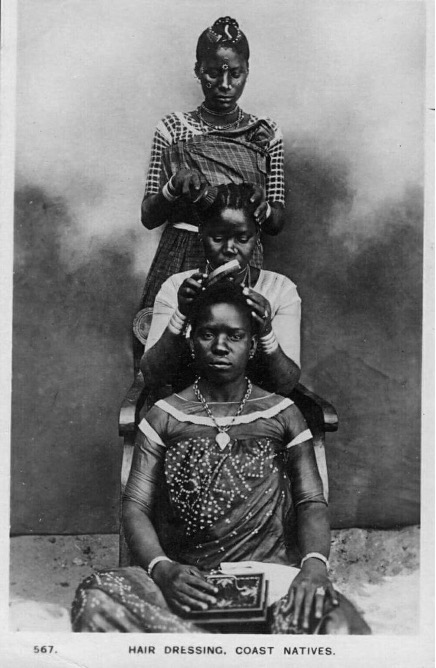

Many slave owners would shave the hair of the African people, but when it grew back it became a lifestyle tool. Women who were allowed to roam further afield became responsible for mapping escape routes (see figs. 5 & 6). Drawing or writing the directions was too risky, therefore many women would braid hair into maps and often hide small bits of gold and seeds to sustain them after escape (Alexander, M. N/A). The auctioning of slaves also placed value on the 'whiteness' of the person being sold. Kinky hair, wide features and dark skin were viewed as unattractive while slaves with lighter skin and softer hair would hold higher value. This deeply damaging mentality has remained engrained in the psyche of black people through generations, resulting in black people having complicated relationships with their natural hair and identity. Slavery ended in 1865, but the psychological scars and constant racism were still very prevalent, meaning many black people would alter their hair to fit a more European ideology around 'beauty'; straight hair and small features being the 'norm' and aesthetically more beautiful. This resulted in many black individuals going to extreme lengths to achieve 'beauty'.

In the late 1800s Madam C.J Walkerdeveloped the "hot comb" also known as the "pressing comb". The first device created and marketed by a black woman for other black women, along with the pressing comb, Walker created this 'hair grower' to promote hair growth and length. The recent Netflix series, 'Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J Walker' explores her journey within the haircare industry in the late 1800s as a black woman. The emphasis on the significance of hair was apparent throughout the series, and the director Kasi Lemmons stated: "more than looking good, the styles of the time were an expression of pride." (Okwodu, J. 2020). The pressing comb gave black women control over their identity and how they styled their hair. However arguably, the comb complied with the Westernised beauty aesthetics and simply encouraged black women to further strip away a layer of their culture and allow oppression to continue. The hair grower projected a desire for long and silky hair, which was and still is naturally unattainable for black women.

The paper 'Black hair culture, politics and change' (Dash, P, 2006. pp 27-37) looks at the centrality of hair to diasporic aesthetics, and how hair becomes a symbol of black resistance to oppression. Dash explains that the Black Power Movement critiqued black popular culture of the time and demonstrated how black peoples' lives in the Western World were marked by the slave trade and the dehumanising effects of racism. Straightening and hair altering were seen to be emblematic of internalised self-hatred, whereas the Afro became the symbol of African celebration, emerging as a marker of black pride. In the 1960s, black liberation movements proposed the slogan 'Black is Beautiful' to contest the hegemony of the white aesthetics with a grounded aesthetic of its own. Fully aware that such hegemony depended on the subjective internalisation of these norms and values, the Afro hairstyle was adopted by Afro-Americans as an outward affirmation of an empowering sense of black pride. If racism is thought to be an ideological code in which a person's biology ranks their societal value, then our hair is perceived within this framework; a burden, with a range of negative connotations. Comparisons of aesthetic values such as the pair 'beautiful/ugly', have been central to the way racism separates the world into binary oppositions in its arbitration of human worth. This racist presence is within everyday comments made about black hair. 'Good hair', means hair that looks 'European', or in other words, straight, not too curly or kinky (Mercer, K. 1987. pp 33-53).

The next chapter will look at the black body on screen, from the 1990s to the present, examining the significance of black aesthetics and how these aesthetics are portrayed on television.

Figure 5: Native African Women Hairdressing

Figure 5: Native African Women Hairdressing

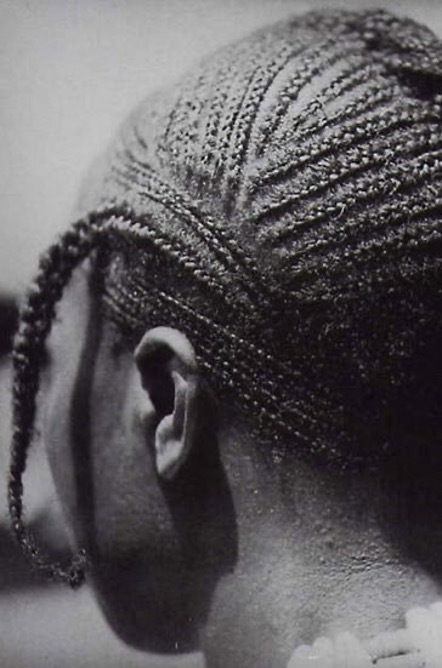

Figure 6: Cornrows in Natural Hair

Figure 6: Cornrows in Natural Hair

THE BLACK BODY ON SCREEN

Until the 1980s, television shows that had a predominate black cast that focused on black themes were under the creative control of white studio and network executives. The white producers of these programmes enforced strict control in order to "discipline, contain and ultimately construct a point of view" (Cheers, I. 2018. pp. 1-5) . Similarly, they represented black women through the view point of middle-class white men, who primarily viewed African-American women as domestic servants. Scholar Patricia Hill Collins examined the stereotypical images of African-American women that have persisted in the media, in her book, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (2000). She explains that "portraying African-American women as stereotypical mammies, matriarchs, welfare recipients, and hot mammas helps justify U.S black women's oppression" (2000. pp.69-79).. Collins further mentions that "these controlling images are designed to make racism, sexism, poverty, and other forms of social injustice appear natural, normal and inevitable parts of every day life". Within the book Collins emphasises the importance of embracing and creating new images to correct these problems.

It cannot be underestimated what negative effects the absence of black people on television had for black viewers, who were unable to see positive cultural representations of themselves within the media. The presence of ethnicities whose dark skin further distinguished them from the majority population's fair skin reveals how the visual medium of television was a particularly acute barometer of how society viewed black people. Both literally (as there were few black faces evident on programmes), and metaphorically, this absence and/or persistently stereotypical representations indicated how hegemonic culture reacted to black people in Britain (Osborne, D. 2016. pp 167-182). By way of example, 'Desmond's'was launched by channel 4 in 1989, and was the first situation comedy series in Britain to be created and scripted by a black writer of African Caribbean descent (Osborne, D. 2016. pp 167-182). Set in South-East London, Peckham, 'Desmond's' barbershop is used as a gathering place for his family and friends. The show captured many of the real-life scenarios of a small family business, and as Sarita Malik (2002) states, "was designed to work against the negative images of comedic blackness which had hitherto been seen on television". Malik's summary divulges the series' importance in representing the ordinary lives of a black family within a representational legacy that had always been overwhelmingly negative, and had before denied black artists of re-sculpting their identities on screen. The creator and star Trix Worrell knew barber shops are a space of endless conversation and gossip; sometimes the chances of getting a haircut were slim. He mentioned, "the black barber is a community and a drop in" […] "And more crucially, a space where black people can just be black" (Davis, R. 2019).

Cultural expression through black hair was continuously changing with the current social and political climate of the time; a correlation between iconic moments in history and the black body. The 70s saw the rise of the Afro, alongside the Civil Rights Movement, followed by a break away from natural hairstyles, since the current trend at the time was all things wet, dried, cut and fried in the 80s (Sinclair, L. 2020). In the 90s and early 2000s, braiding styles were seen as a physical depiction of 'black girl magic'. Seeing black women such as 'Brandy' on TV screens in the 90s, was an iconic moment for the black community. An array of braided hairstyles were seen on her television series _'_Moesha' (Sinclair, L. 2020). Alongside this, the US sitcom 'Sister, Sister,'debuted in 1994 and almost every member of the cast was black. Not intending to be a "diverse" show, 'Sister, Sister's' all black universe was created entirely for black audiences. It could be perceived that this was TV-style segregation, but in actuality, it was a response to an overwhelmingly white Television climate. The majority of white sitcoms did not reflect the black community (Frazer-Carroll, M. 2020). Television shows like 'Moesha' and 'Sister, Sister' embodied black culture in the 90s, giving viewers a sense of pride as their traditions and lifestyles were finally recognised on screen. Similarly, the shows elucidated the idiosyncrasies of black homes, fashion, music, food and humour.

Sociologist Ingrid Banks (2000) has stated that the 1990s redefined a social climate that acted to nurture black cultural expression in response to racism. This decade brought a sense of cultural nationalism and afrocentric aesthetics when it comes to hair and dress in black America, andboth natural and straightened styles were worn relatively equally. Documentary filmmakers were also exploring the history of black hair's artistic expression. In 1998 hairstylist Yvette Smalls, explored the historical and cultural meaning of black hair in a forty-minute documentary titled 'Hair Stories'. Similarly, the comedian Chris Rock also made a documentary exploring the definition of 'good hair' which holds colossal value within the black community, as Rock recognised first hand after his black daughter asked, "Daddy, how come I don't have good hair?". Prompted by this question Rock created the documentary 'Good Hair' (2009), to explore the African-American identity through the medium of hair. Chris Rock's film is a well-researched study about what are known to be racist attitudes towards black physical appearances. For example, people with 'good hair' (straight hair) are more than likely to get better jobs and be seen as more attractive, in comparison with 'nappy' hair which is deemed ugly and associated with black people.

The preoccupation with fitting the media-supported concept of beauty has given rise to an industry worth billions of consumer money every year, with many black women purchasing products to alter their hairstyles. Throughout the documentary the term 'good hair' is often referred to as, "something that looks relaxed and nice" (2009). The term 'relaxed' comes from the process of using relaxer; whose base chemical is sodium hydroxide, and which straightens out curls in hair (Lorch, M. 2018). Within the documentary, in an interview with the actress Tracie Thoms, she explains how the "first time I got relaxer I thought, now I'm pretty". This doctrine of European features being the ultimate definition of beauty is incredibly detrimental. The hegemonic beauty standards that are portrayed throughout the documentary are still present in society today. Introduced first to children, the subsequent intergenerational transfer of these ideas is virulent. Rock's documentary saw children as young as three having their hair 'relaxed' with harmful chemicals that would often burn and leave scars, purely for the satisfaction of having 'good hair'. Moreover, 'Good Hair' explores the significance of black hair, and the importance of hair salons and barbershops within the African-American community. Exposing the beauty contained within the black hair community to the public allows a continued resource for people, especially those of black descent, tackling the cultural violence that has so often been overlooked the beauty and entertainment industry. As well as this, within the documentary it becomes clear that beauty parlours and barbershops are sanctified spaces for the black community. In her essay "The Art of the Ponytail," African-American writer Akkida McDowell recollects her childhood beauty parlour experiences and explains how she, "enjoyed this nurturing ritual and scarcely noted the tugging and twisting. I bonded with my grandmother and my mother and flourished in the company of the women in the shop". The once sacred rituals of thousands of African Tribes has retained the trauma and suffering of the Slave Trade, and is again being reinforced as the art form it always has been.

Unfortunately, cultural violence is still operating in both psychological and symbolic areas. The internalization of its ideology means that the quest for beautiful hair is shaped by the experiences of cultural violence for many African-American women (Oyedemi, T, 2016. pp 1-15). Images of 'beautiful' women and celebrities often closely resemble a certain idea of body type and hair that are unattainable and unnatural to black women. Even though women are often more vocal about their desires to alter their hair, black men are also affected. Jack Thompson had a black mother and a white father, and was told in 1980s Kansas City that thanks to his dad he had a, "good head of hair". However, Thompson wanted perfectly straight hair like his father, and begged his mother to take him to the barbershop in order for it to be straight. "I wanted to be white." Recalls Thompson, (D, Byrd & L, Tharps, 2001). Evidently, there is still an unmoving binary of social acceptability for fine European hair, and a continued level of social unacceptability of African natural hair.

Shonda Rhimes produced the show 'How to Get Away with Murder' (2014), and the incredibly popular television shows Grey's Anatomy and Scandal. Nominated for several awards, this level of success has been widely recognised as unprecedented for a black woman. 'How to Get Away with Murder' premiered in 2014, and the black actress Viola Davis plays Annalise Keating, a protagonist that is assertive, strong, emotional, smart, sexually active and queer. It is arguably unparalleled for a dark-skinned black woman to embody all of these complexities and 'contradictions' on primetime network television (Rowe, K. 2019). A particular scene in 'How to Get Away with Murder' shows the character Annalise Keating in a vulnerable position, first removing rings from her hand, Keating then removes her wig that she has worn consistently throughout the season, to reveal her natural kinky hair texture; flat, matted and un-styled from sitting beneath a wig all day (see fig. 7). Buzzfeed writer Alison Willmore states "on 'How to Get Away with Murder', Viola Davis' removal of a wig, then eyelashes, then makeup, was played like a warrior shedding pieces of plate mail after returning from war" (Willmore, A. 2014).

Figure 7: Annalise Keating’s Wig Removal

Figure 7: Annalise Keating’s Wig Removal

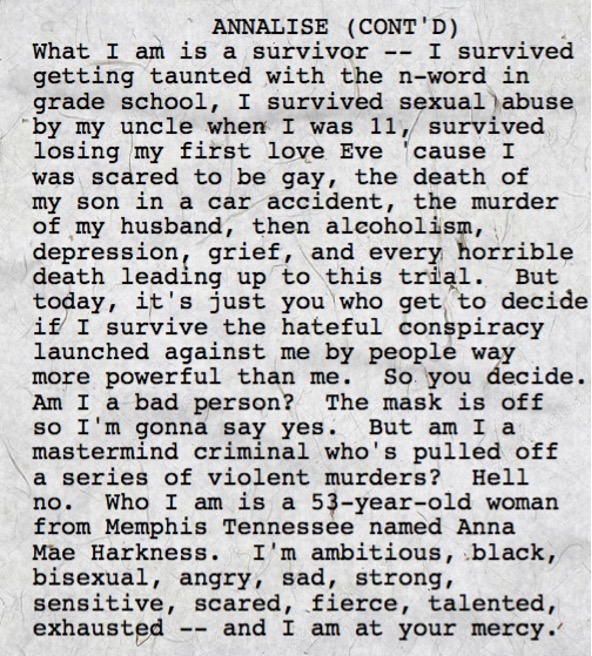

Figure 8: Annalise Keating’s Monologue, 2020

Figure 8: Annalise Keating’s Monologue, 2020

The actress Viola Davis herself often chooses to go natural with her hairstyles. In 2012 she wore her natural, short and golden-brown afro on the red carpet of the Essence Black Women in Hollywood celebratory Oscars luncheon. Black women everywhere celebrated, and voiced their support for the look and for Davis' choice to deviate away from altering her natural hairstyle. Davis says her choice for wearing her natural afro at professional occasions was inspired by her husband, calling it a "powerful statement". However, some people such as black celebrity show host Wendy Williams joked that she did not want to see "a room 222 look" on the red carpet (Rowe, K. 2019), giving the impression that natural hair isn't acceptable enough for the class of the red carpet. The statement, as abrasive and contradictory as it is (as Williams herself is a black woman with natural hair) is not surprising. Black women echo the same sentiments throughout the media, these women are generally projecting the hurt and racist expressions they've internalised since childhood.

'How to Get Away With Murder' saw Viola Davis changing how black women are portrayed on screen through playing the iconic character, the paradigm slowly shifting from cliché, through to complex and raw protagonists. In the final season the character strips away the armour she carries; wigs, heavy make-up, and tight clothes, to reveal a natural and raw black woman. To many this would be seen as a casual choice for Keating, however it is a pivotal moment in the show and in the television industry as a whole. In an interview with Refinery29, Viola Davis explains that when she signed onto the show, one of her stipulations was to portray a real woman, not an extension of a male fantasy. Regardless of whether the character made people uncomfortable, Davis wanted to convey a character that was flawed, honest and real from the start and by doing this she was making a larger statement about how black women are recognised and perceived on screen (Quinn, K. 2017). In the series final, Annalise Keating faces a jury that needs to establish whether Keating is guilty of multiple charges and to this she decides not to wear a wig and wear her hair natural. She states, "I've worn a mask every day of my life," providing examples of the multiple things she has done in the past to be accepted in the white male dominating World of law, such as styling her hair in a particular way to come across professional, considered one to listen to, and ultimately more attractive. "At the law firm, I wore heels, make-up and a wig," she continues. As she faces the jury the viewers can almost see the protective shield being stripped off Keating as she lists her flaws and speaks her truth. It is at this essential point, that many black women viewers can find themselves within the protagonist, they understand the battle does not only lie within the roots of their hair, but the societal system that has consistently reminded black women of their inferiority to white women, white men, and everyone else. The creator of 'HTGAWM'Peter Nowalk (2020) posted on the social media platform Twitter, a picture of Annalise's speech from the final episode script, stating, 'Viola Davis started our conversation talking about the masks we all wear. 6 years later, I've learnt most of my job is listening.' Followed by the iconic lines of Annalise Keating's plead for innocence (see Figure 8) revealing her flaws and vulnerability. It is rare we see a black woman character so vulnerable yet powerful within her field of work, which makes Annalise Keating a significant character for black women to find themselves within.

We can see that having key characters on television play a vital role in black peoples lives, but does this same principle apply to the music industry? Following on from this, the next section of the paper will be investigating the complexities of the music industry in regards to the black aesthetic.

THE RISE OF HIP-HOP CULTURE

Hip-hop emerged in the 1970s out of the post-civil rights era "as art form that [was] spiritually connected to Africa and its people" (Hill S, & Ramsaran, D. 2009).It originated in the predominately African-American economically depressed South Bronx section of New York City in the late 1970s and since its emergence in the mass media mainstream in the 1990s, hip-hop culture has affected the arenas of film, fashion, television, art, literature, and journalism (Watkins, S. 1999). Black women performers, songwriters, and producers, including Erykah Badu, Missy Elliott, and Lauryn Hill, profoundly affected hip-hop culture. While most music videos intensify the exploration of the black women's body and preserve stereotypes of black womanhood, Badu, Elliott and Hill depict themselves as independent and self-reliant agents of their own identity (Emerson, R. 2002). The 2000s saw a second wave of the natural hair movement, andmany black creatives were honouring their history and birthright by designing their hair to symbolise the rich culture of Africa. The recent film 'Black is King'by pop star Beyoncé, is a prime example of how people are respecting their heritage through hair. The film is enriched with African traditions, honouring the black community, and hair plays a key role (King, A. 2020). Beyoncé's hairstylist, Neal Farinah (2020), celebrated black beauty by creating floor-length braids, silky weaves, and Bantu knots, explaining that "to African women throughout history [hair] was something spiritual, your hairstyle represented your power."

Similarly Beyoncé's album, 'Lemonade', introduced the concept of the "Bad Bitch Barbie", a term used to identify a woman who embraces her body, while simultaneously using it as a commodity. Portraying the black body ideal in 'Lemonade', Beyoncé uses images of black women's bodies to express empowerment, boldness, and resilience to living in a racist and sexist society where black women are rarely accepted (LaVoulle, A & Lewis Ellison, T. 2017. pp 66-80). The "Bad Bitch Barbie" concept recognises the objectification of Beyoncé's body and reclaims it to her own benefit. Developing and redirecting the kinds of words often used to destroy a black women's demeanour, Beyoncé and many other female singers and/or rappers use them as a means for self-empowerment. Through visual representation eyoncé challenges the sexual script by taking control of her own body and sexual expression. In her song, "Don't Hurt Yourself" she disrupts the sexual script with unapologetic lines such as, "You ain't married to no average bitch, boy." In this line, she represents herself as a "bitch," but makes it knowledgeable to listeners that she is not an average woman, reclaiming the word as a statement of empowerment and strength. Using both the music and video imagery of "Don't Hurt Yourself," Beyoncé illustrates her "Bad Bitch Barbie" status, thus representing both bodily and monetary success. Despite the confidence she often displays, Beyoncé also uses her voice to acknowledge certain aspects of womanhood that have been damaged since girlhood. In the hip-hop song "Flawless," Beyoncé exemplifies Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's TEDx Talk 'We Should all be Feminists' to demonstrate ways black women's voices have been silenced and limited since childhood:

We teach girls to shrink themselves: you should aim to be successful, but not too successful; Otherwise, you will threaten the man. We raise girls to see each other as competitors—not for jobs or for accomplishments...but for the attention of men. We teach girls that they cannot be sexual beings in the way that boys are, for fear of being labeled as promiscuous (Adichie, C. 2012).

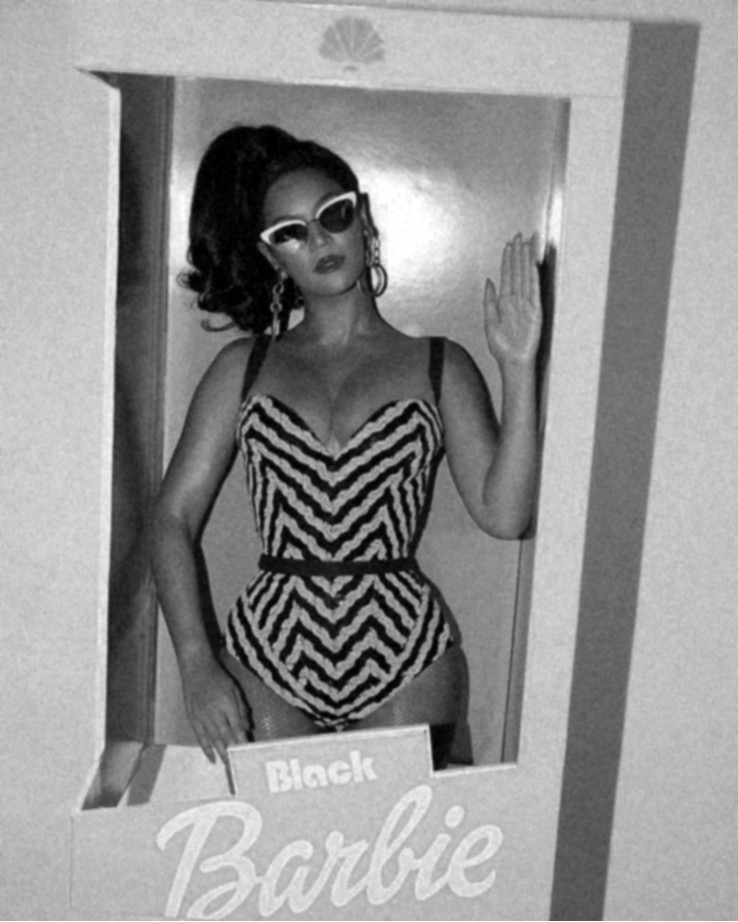

In Figure 9 Beyoncé is seen photographed dressed as a Barbie doll, thus affirming the presentation of her image; embracing her sexual image and using it as a commodity. Lemonade's'album represents the continued emotions and expressions felt by women who are hurt, vindicated, and betrayed. Through visual-imagery and song lyrics Beyoncé reflects a multi-dimensional narrative that acknowledges many women's struggles and highlights the diversity of the black female body. It visually demonstrates the ideas of "Black Girl Magic" and the struggle for true self-love and acceptance. Also, the album represents black mothers who have lost their sons to police violence and other social injustices, including Sybrina Fulton, the mother of Trayvon Martin, who was murdered by a Neighborhood Watch coordinator; Lezley McSpadden, the mother of Michael Brown, who was killed by police; and Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner, who was also killed by police), (LaVoulle, A & Lewis Ellison, T. 2017. pp 66-80).

Figure 9: Beyoncé photographed as Black Barbie, 2016

Figure 9: Beyoncé photographed as Black Barbie, 2016

Since the 1970s Hip-Hop and Rap music has always been an artistic expression and outlet for many black individuals whom face hate crime and injustice. N.W.A were a hip-hop group formed of rappers, Eazy-E, Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, MC Ren, and DJ Yella in 1987 (Grow, K. 2018). Their lyrics were revolutionary, but on the contrary many condemned the music and its creators, radio stations and MTV refused to add the songs to their playlists and even politicians would launch attacks. The group highlighted the hedonism and violence of gangs, poverty and drug dealing, calling themselves "Street reporters". Their music was unhinged and raw, reflecting the real lives of many black neighbourhoods in America and normalities of growing up a black man in an American society dominated by systemic racism and injustice. eyoncé Their music became an outcry for many black men and even women at the time because it represented the real lives of the people, it carried the weight of what black experiences were. The most notorious song "F*k tha Police" became a rally cry in Los Angeles after a group of white police officers took part in a savage beating of the unarmed black motorist, Rodney King (Kennedy, G. 2017). The three words because a revolutionary slogan, graffitied on walls and shouted across the city by those who torched it days after the acquittal. Now, 32 years after its release, the song is surging again as the Black Lives Matter and George Flloyd protests hit the streets of America. "A lot of people would be happy that [their] song gets streamed," says MC Ren, "but it's unfortunate." (Bernstein, J. 2020). The same political battle remains, the ongoing injustice and racist society is continued even 70 years after the Civil Rights Movement. What is relevant here is that music is the artistic expression and activism in response to cultural violence, it is a representation of every day life for black individuals, and a spatial identity within the black community.

It could be argued that the black music industry is a leading example of embracing the black aesthetic and black hair styles. From music videos and photoshoots black people are expressing their heritage through hair. Having this represented in popular culture is a step forward in natural-hair acceptance and appreciation. However, many black people today still fearful about leaving their natural black hair visible will result in being fired; that it is, "too messy for the industry" or that having your hair styled in dreadlocks will block any opportunities to be promoted. It is evident that the intergenerational transmission of "bad hair" equating to anything from curly to afro, braided to dreadlocked, is still notably oppressed. Nevertheless, with A-list celebrities like Beyoncé, NWA and rapper Kendrick Lamar singing lyrics such as, "show me somethin' natural like afro on Richard Pryor," it creates a space where black people can learn to appreciate and accept their natural hair and embrace its beauty (Sang, R. 2017).

Conclusion

Throughout the 1990s to the present there has been an underlying racist rhetoric in relation to the black body, and this can be seen in all form sof media, but especially on television and in music. It remains the case that to produce and sustain a self-defining presence for black people on screen (within a prejudicial context) remains an unfinished venture. Many television shows and artists have contributed positively in representing black identities and culture in the media, however there still remains a disproportionate under-representation of black people on screen. Storytellers, influencers, and celebrities with structural power need to redefine beauty in its multicultural nature. Images of black people wearing their hair natural, braided or styled in a way that compliments the natural textures of their hair needs to be common in the mass media in order to enable acceptance in society. Similarly, images and music lyrics need to affirm self-love within the black community and use this positive affirmation influence viewers. Empowerment comes from rejecting the objectification, commodification and exploitation of black people. This article has show that artistic expression is a way to challenge hegemonic beauty standards, and to convey the black aesthetic through vernacular visual language.

The internalisation of racial beauty standards is a societal problem that starts within the childhood of many black people. Therefore parents have a pivotal role in the upbringing of new generations to follow; parents need to model the example that celebrates natural hairstyles for their children (T, Oyedemi. 2016). The consequence of not doing this is the continuation of a generational pattern of identity erasure. Similarly, a better educational system that is designed to shatter old myths would effectively challenge hegemonic ideologies and cause less emotional suffering throughout adulthood for black individuals. Notably, the comfort and prosperity of white people in America and many European counties like the United Kingdom are built on the backs of enslaved African people, the displacement and death of Native Americans (in the US), and the exploitation of land and people all around the world. Racism is embedded within the kinds of history taught in US schools and many other countries, and whilst it is in the past it is still very much part of todays reality. Images that we see in the media today surrounding the ongoing protests in America rarely differ from those from the 1970s. The systemic racism is created by the societal structures and political levers within society. People created these structures and therefore have the power to alter and change them for the better. Clearly, to undo the pattern of cultural violence society needs to re-write the cultural script.

Shifting the analysis to explore how the metric of authority is structured along race, gender, class, sexuality and nation - as well as how it operates through interconnected domains of power - structural, interpersonal, disciplinary, and hegemonic - reveals that the dialectical relationship linking oppression and activism is far more complex than simple models of oppressors (Collins, P, H. 2000. pp 305-307).

This article has offered analysis of beauty as social oppression and inequality, initially through the lens of black hair. It has discussed the history and impact of political and societal movements such as The Civil Rights Movement and Black Lives Matter in relation to black power, and the correlation it has in representations of the black body. In particular it has examined the significance of hair within the black community and its symbolism throughout history. The complicated and complex relationship surrounding natural black hair is posed as a response to oppression and enforced Eurocentric beauty ideals. It becomes clear that portraying the black body through music, television and artistic expression can be the initial turning point in rewriting the cultural script, inaugurating personal transformation, empowerment and acceptance for black people. Black hair is presented within this framework, and given as one example amongst many.

Bibliography

Alexander, M., n.d. Not Just A Fashion Statement: The Significance Of Afro Hair's History. [online] Lush Fresh Handmade Cosmetics UK. Available at: <https://uk.lush.com/article/not-just-fashion-statement-significance-afro-hairs-history> [Accessed 16 October 2020].

Banks, I., 2000. Hair Matters: Beauty, Power, And Black Women's Consciousness. 1st ed. New York: New York University Press, pp.10-40.

Bernstein, J., 2020. Streams Of N.W.A's 'F-K Tha Police' Nearly Quadruple Amid Nationwide Protests. [online] Rolling Stone. Available at: <https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/fuck-tha-police-streams-protest-songs-george-floyd-1009277/> [Accessed 14 January 2021].

Bryant, S.L., 2013. The Beauty Ideal. Columbia Social Work Review, 11(1), pp.80-91.

Byrd, D. and Tharps, L. (2001) Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. New York: St Martin's Press. pp. 4-7.

Cheers, I., 2018. The Evolution Of Black Women In Television. 1st ed. New York: Routledge, pp.1-5.

Chisolm, K., 2018. The Cultural Legacy Of Yoruba. [online] Articulate. Available at: <https://www.articulateshow.org/articulate/the-cultural-legacy-of-yoruba> [Accessed 12 January 2021].

Dash, P. (2006) 'Black Hair culture, politics and change', International Journal of Inclusive Education, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 27-37.

Davies, R., 2019. Desmond's At 30: 'I Wrote It For White People'. [online] The Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/jan/04/desmonds-at-30-i-wrote-it-for-white-people> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Emerson, R. (2002) '"Where My Girls At?": Negotiating Black Womanhood in Music Videos', Gender and Society, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 115-135. doi: 29 November 2020.

Frazer-Carroll, M. (2020) Sister, Sister is back: In praise of the Nineties black sitcom boom. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/features/sister-sister-netflix-black-sitcoms-fresh-prince-b1721659.html (Accessed: 29 November 2020).

Grow, K., 2018. N.W.A's 'Straight Outta Compton': 12 Things You Didn't Know. [online] Rolling Stone. Available at: <https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/n-w-as-straight-outta-compton-12-things-you-didnt-know-707207/> [Accessed 15 January 2021].

Good Hair. (2009) [film] Directed by J. Stilson. United States: HBO Films, LD Entertainment, Chris Rock Productions.

Hill Collins, P., 2000. Black Feminist Thought. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, pp.69-79.

Hill, S. and Ramsaran, D., n.d. Hip Hop And Inequality: Searching For The Real Slim Shady. 1st ed. United States of America: Cambria Press, pp.11-34.

Kennedy, G., 2017. The Moment N.W.A Changed The Music World. [online] Los Angeles Times. Available at: <https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/la-et-ms-nwa-parental-discretion-20171205-htmlstory.html> [Accessed 11 January 2021].

King, A,. (2020) How Beyoncé's Longtime Hairstylist Created the Head-Turning Hair of Black Is King. [online] Vogue. Available at: <https://www.vogue.com/article/how-beyonces-long-time-hairstylist-created-the-head-turning-hair-of-black-is-king> [Accessed on 17 October 2020].

LaVoulle, C. and Lewis Ellison, T., 2017. The bad bitch barbie craze and Beyoncé African American women's bodies as commodities in Hip-Hop culture, images, and media. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 16(2), pp. 7-80.

Lorch, M., (2018)The Chemistry Of Hair Relaxers – Chemistry Blog. [online] Chemistry-blog.com. Available at: <http://www.chemistry-blog.com/2018/01/31/the-chemistry-of-hair-relaxers/> [Accessed 17 October 2020].

Malik, S. (2002) Representing Black Britain: Black and Asian Images on Television. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

McCluney, C., Robotham, K., Lee, S., Smith, R. and Durkee, M., 2015. The Costs Of Code-Switching. [online] Harvard Business Review. Available at: <https://hbr.org/2019/11/the-costs-of-codeswitching> [Accessed 14 January 2021].

Mcdowell, A. "The Art of the Ponytail" in Edut, O. (1998) Adiós, Barbie: young women write about body image and identity. Seattle: Seal Press

McWilliams, A., 2018. Sorry To Bother You, Black Americans And The Power And Peril Of Code-Switching | AT Mcwilliams. [online] The Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/jul/25/sorry-to-bother-you-white-voice-code-switching> [Accessed 15 December 2020].

Mercer, K. (1987) 'Black Hair/Style Politics', new formations, number 3 Winter, pp. 33-53.

Nowalk, P. (2020) .@violadavis started our first conversation talking about the masks we all wear. 6 years later, I've learned most of my job is listening. #HTGAWMFinale [Twitter] 15 May. Available at: https://twitter.com/petenowalk/status/1261125092160897030 (Accessed: 19 December 2020).

Okwodu, J., (2020) With Netflix's Self-Made, Black Beauty Pioneer Madam C.J. Walker Finally Gets Her Due. [online] Vogue. Available at: <https://www.vogue.com/article/self-made-madam-cj-walker-netflix-kasi-lemmons-interview>

Osborne, Dl. (2016) 'Black British Comedy: Desmond's and the Changing Face of Television', British TV Comedies, N/A, pp 167-182).

Oyedemi, Tl. (2016) 'Beauty as violence: 'beautiful' hair and the cultural violence of identity erasure', Social Identities, Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture, pp. 1-15.

Quinn, C., 2017. How Viola Davis Learned To Walk The Red Carpet On Her Terms. [online] Refinery29.com. Available at: <https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2017/02/142397/viola-davis-natural-hair-makeup-beauty-meaning> [Accessed 21 December 2020].

Rowe, K., 2019. "Nothing Else Mattered After That Wig Came Off": Black Women, Unstyled Hair, and Scenes of Interiority. The Journal of American Culture, [online] 42(1), pp.21-36. Available at: <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jacc.12971> [Accessed 9 December 2020].

Sang, R,. (2017) Attack of the Afros!. [online] IndustryMe. Available at: <https://industryme.co.uk/attack-of-the-afros/> [Accessed on 17 October 2020].

Sinclair, L. (2020) Black hairstyles: "Why 'the Brandy' was the most significant hairstyle of the 90s". Available at: https://www.stylist.co.uk/long-reads/black-women-hairstyles-afro-natural-hair-box-braids-microbraids-moesha-brandy-janet-jackson-rihanna/316585 (Accessed: 29 November 2020).

TEDxEuston (2012) We should all be feminists. Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_we_should_all_be_feminists?language=en (Accessed: 3 January 2021).

Watkins, S. (1999) Representing: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema. United States of America: The University of Chicago Press, Ltd,.London.

Willmore, A., 2014. Why Hollywood Is Suddenly Obsessed With Black Women's Hair. [online] BuzzFeed. Available at: <https://www.buzzfeed.com/alisonwillmore/the-latest-exploration-of-the-complex-dynamic-between-black> [Accessed 23 December 2020].

List of Figures

Figure 1:

Jerome, Aries. (2017) Divalocity. [image] Available at: https://divalocity.tumblr.com [Accessed 4 December 2020]

Figure 2:

Niven-Phillips, L. (2014) L'Or é al Paris Signs Naomi Watts. [image] Available at: https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/naomi-watts-new-loreal-paris-spokesperson [Accessed 4 December 2020]

Figure 3:

Starling, L. (2016) Prinicess Nokia Honors The Spirits Of Her Afro-Latina Heritage In "Brujas" Video. [image] Available at: https://www.thefader.com/2016/11/07/princess-nokia-brujas-video [Accessed 5 December 2020]

Figure 4:

Starling, L. (2016) Priincess Nokia Honors The Spirits Of Her Afro-Latina Heritage In "Brujas" Video. [image] Available at: https://www.thefader.com/2016/11/07/princess-nokia-brujas-video [Accessed 5 December 2020]

Figure 5:

N/A (2020) Black Hair, Media & America: A twisted history. [image] Available at: https://www.naturalhair-products.com/black-hair-media.html [Accessed 5 December 2020]

Figure 6:

Sharma, C (2018) Africans Used To Hide Escape Maps From Slavery In Their Hairstyles. [image] Available at: https://edtimes.in/africans-used-to-hide-escape-maps-from-slavery-in-their-hairstyles/ [Accessed 6 December 2020]

Figure 7:

Frost, C (2014)'How To Get Away With Murder' Star Viola Davis Explains Why Annalise Keating's Wig Has To Come Off. [image] Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2014/10/29/viola-davis-how-to-get-away-with-murder_n_6068486.html [Accessed 10 January 2021]

Figure 8:

Nowalk, P (2020) @violadavis started our first conversation talking about the masks we all wear. 6 years later, I've learned most of my job is listening. _#HTGAWMFinale.[image] Available at: https://twitter.com/petenowalk/status/1261125092160897030 [Accessed 10 January 2021]

Figure 9:

White, C (2016) 'Black Barbie': Beyonce shows off her curves in skimpy swimsuit and fluffy hot pink jacket to dress as iconic doll on Halloween night out with Blue Ivy and her Ken Jay Z. [image] Available at: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3892458/Beyonce-transformed-vintage-Barbie-Halloween-night-Blue-Ivy-Ken-Jay-Z.html [Accessed 20 December 2020]