Introduction

Self-care, a word formed of two compounds: self, a reflexive pronoun meaning 'auto' and conveying a notion of identity (Foucault, 1988, p. 25); and care, a noun signifying "the process of protecting someone or something and providing what that person or thing needs " (Care, n.d). Therefore, self-care is the practice of providing for oneself what oneself needs, but what do we need?

In contemporary Global North 1 mainstream discourses you may have often seen self-care portrayed as a set of occasional individual practices (see Figure 1), done in a non-reflective manner, such as eating healthily, socialising, having a routine, sleeping well, and exercising regularly. These narratives, however, often dismiss the fact that socioeconomic, political, cultural and geographic factors may play a role in whether these self-practices are attainable. Now, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, caring for ourselves through personal responsibility and solidarity, and consequently for others, has become an essential collective human action to prevent illness, especially when care services are overwhelmed or unavailable.

Many years before this pandemic, Michel Foucault, expert in "the history of thought" (1988, p. 10) offered some insights into the care of the self. He developed a body of work that analysed "the specific techniques that human beings use to understand themselves" (1988, p. 18), one of them being the technologies of the self.

[The] technologies of the self (…) permit individuals to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection or immortality. (Foucault, 1988, p. 18)

This definition identifies self-care as a series of operations, continuous and active, and highlights that the help of others might be required, thus alluding to the need for collective care. It reinforces a range of areas which an individual can affect; the body, the soul, the mind, and the way of being and living. He refers to self-care as a way of obtaining a state of enlightenment and transcendence in one's own being, which considering the current socioeconomic, political and health landscape goes beyond what may be attained by most individuals.

This investigation explores the intersection between self-care and injustice, with a specific focus on the existing global inequalities that the Global North capitalist systemleads to. Capitalism is "an economic system" in which "the bulk of the means of production is privately owned and controlled" (Gilabert, O'Neil, 2019). This system creates a "class division" (Ibid., 2019), thus hierarchizing people by socioeconomic status. It is a system that creates uneven personal and political power relations and disproportionate living conditions, which might consequently affect the opportunity and access to perform self-care.

This essay aims to explore the following question: In what way can self-care confront inequality? Firstly, we will analyse factors or reasons which influence a community's opportunity to perform self-care: agency and accessibility. Lastly, we will highlight a series of past and present self-organised responses to the lack of access to self-care practices and knowledge.

Figure 1. NHS Self Care Week (2021) poster, featuring the abovementioned activities that one must partake in, individually, to be well, which are prevalent in the rhetoric of societies and healthcare practitioners regarding health and wellbeing.

Figure 1. NHS Self Care Week (2021) poster, featuring the abovementioned activities that one must partake in, individually, to be well, which are prevalent in the rhetoric of societies and healthcare practitioners regarding health and wellbeing.

Self-Care Agency

Within a capitalist system, there are a plethora of reasons that may shape someone's opportunity to care for their "physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual and energetic" wellbeing (Pikara Magazine, 2019). This part of the investigation focuses on two factors: self-care agency, and accessibility to practices and knowledge.

Agency is defined in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as "the exercise or manifestation" of "the capacity to act" and "the performance of intentional actions" (Schlosser, 2019). It is an ability to perform certain actions and connotes a purpose and determination, alluding to a sense of power and capacity to decide. Foucault (1988, p. 14) believed that "the way people act or react is linked to a way of thinking, and of course thinking is related to tradition." What we think of ourselves, relates to how we act with ourselves, therefore how we care for ourselves. He adds that those thoughts come from tradition, meaning that certain self-perceptions may be founded upon years of intergenerational self-portrayals that are passed down, which will shape an individual's sense of agency. Rather than self-care being a series of occasional actions, it is a self-practice that requires certain abilities, therefore of self-care agency. As defined by Patricia A. Carter:

Self-care agency is a person's ability to engage in self-care, that is, performs actions to meet individual health care needs. [It] means an individual possesses the (…) skills necessary to assess, interpret, and take purposive action to ensure that one's health and well-being are maintained. This (…) does not mean that the individual who has high self-care agency is able to exist in a vacuum devoid of others, or that they never require assistance from others to maintain physical and mental health. It means more correctly that the individual will utilize resources from the environment to preserve personal health. (Carter, 1998, p. 198)

This is the most used definition of self-care agency in medical and nursing research studies. The following sections will analyse this definition in detail, by looking at the concepts that stem from it and their relationship to self-care in a capitalist system marked by inequality.

Capability Approach

Self-care agency is someone's ability to engage in self-care. Abilities "are a kind of power, (…) [the] properties of agents" and they "relate agents to actions" (Maier, 2020). This definition indicates an ownership over one's powers to perform certain actions. The Capability Approach, "articulated by the Indian economist and philosopher Amartya Sen in the 1980s" (Wells, n.d.) is a human welfare theory that argues that for humans to achieve a state well-being, not only does the freedom, right or power to do so need to be available, but also certain capabilities, "the required means" to "achieve their potential doings and beings." Doings are activities one can undertake, and beings is the kinds of people we can be (Robeyns, Byskov, 2020).

Whether someone can convert a set of means - resources and public goods - into a functioning (…) crucially depends on certain personal, socio-political, and environmental conditions, which, in the capability literature, are called 'conversion factors'" (Robeyns, Byskov, 2020) which are the "actual abilities to convert resources into valuable outcomes. (Wells, n.d.)

Sen illustrates this theory through the idea of a bicycle (Wells, n.d.). Whether a bicycle is a means of transportation will depend on whether someone can use it as such. If someone without legs tries to use it, the 'conversion factors' are missing, thus, it will not fulfil this function. Following this example, when referring to achieving well-being through self-care, this means that having the right circumstances is vital to transforming certain available goods into 'functionings'. For example, even if healthy foods are available and economically affordable, if an individual lacks the knowledge, skills or living conditions, also known as 'conversion factors,' to transform these foods into favourable outcomes, these sustenance and self-care needs may not be fulfilled. We may argue that the focus of Western welfare institutions should be on ensuring citizens have the skills and information to perform such practices, adapting them to their circumstances and needs, rather than consistently using a standard rhetoric on individual self-care (as seen in Figure 1).

Empowerment versus 'Responsabilization'

As seen above, self-care fulfils "individual needs", but an individual should not live in a "vacuum devoid of others" (Carter, 1998, p. 198). This acknowledges our need for collective care, which we will delve into later. A fulfilment of individual needs also fulfils a collective need, as Foucault's interpretation of Socrates reads: "in teaching people to occupy themselves with themselves, he teaches them to occupy themselves with the city" (Foucault, 1988, p. 20)."A city in which everybody took proper care for himself would be a city that functioned well" (Foucault, 1997, p. 287). In these examples good self-care is a sign of good citizenship and a contribution to society, personally and professionally. For the ancient Greeks and Romans (Foucault, 1997, p. 285), the concern with the self was a symbol of right conduct and of the practice of freedom. Foucault continues to say that taking care of oneself was, in essence, a practice of ethics, of rejecting a position of submission, consequently exercising self-governance.

Exercising one's self-care agency can present two extreme scenarios that often coexist. It may be empowering and liberating but may also shift the responsibility of the care from the governments and public institutions onto the individuals. Gandhi, Foucault, and the Politics of Self-Care (Godrej, 2017) analyses Gandhi's and Foucault's thoughts on food politics and practices of self-care. It explores self-care agency in the previously noted spectrum, from emancipatory to 'responsibilizing' (p. 907). Gandhi's "organization of a mass movement against colonialism in an underdeveloped agrarian society in the (…) twentieth century" (p. 895), revolved around "politicizing the fulfilment of everyday sustenance" (p. 896), one of the pillars of self-care. He believed that colonialism brought forth seductive goods for the palate, which had detrimental effects on health (p. 898). The rejection of the colonial foods and diets, which Gandhi pushed for, may be deemed "emancipatory" and an "individual assertion of self-control" as a form of "[rejecting] hegemonic authority" (p. 900). Ultimately, this rejection is a form of using one's personal decision as a way of exercising one's political power.

Godrej argues that Gandhi's concerns foreshadow "contemporary biopolitical concerns (…) in which the Western diet overloads the body with toxins, turning it into a site for the collaborative profit motives of the medical, pharmaceutical and nutrition industries" (pp. 898-899). Here, the body is personified, it is a container filled up by the food industry with unhealthy over-consumption, which often leads to disease, thus profiting the wallets of the above-mentioned companies. Regardless of the different contexts of Gandhi's claims and contemporary food politics, resisting the attractiveness of certain products through self-control is a confrontation to manipulation and it empowers an individual's decisions. However, as deeply political as every decision is, it also shifts the responsibility onto the consumer to make whichever decisions are best for their own health.

This phenomenon is known as 'responsibilization,' the process whereby subjects are responsible for a process which would have previously been the duty of another entity, usually a state institution (Wakefield, Fleming, n.d.).Feeding Frenzy (2013), a documentary about the food industry and the health crisis it has triggered in the US, debates the sense of individual responsibility regarding food choices. The featured experts argue that consumers are wrongly portrayed as lazy, to blame for their health conditions and lacking in willpower to eat well. They claim that the food environments, defined as the "conditions that affect the availability, accessibility, affordability and attractiveness of foods and drinks" (European Public Health Alliance, 2019) are "really driving the problem" in the worsening of certain health conditions, such as "obesity-related chronic diseases" (Feeding Frenzy, 2013).

This shift in responsibility triggers self-blame, it denies the absence of structures that facilitate healthy habits and ignores many citizens' lack of 'conversion factors' to use certain resources favourably. This is reinforced in TV shows such as The Biggest Loser, where contestants are "weighed shirtless on national television, forced to exercise for as many as eight hours each day" (Gilbert, 2020). These shows wrongly equate health to the number on the scale and are the embodiment of public displays of individual 'responsabilization' (Wakefield, Fleming, n.d.) on food consumption and exercise habits. The World Health Organisation, WHO, calculates that in 2016 obesity had tripled worldwide since 1975 (WHO, 2020). Kelly D. Brownell (Feeding Frenzy, 2013) highlights that this is a worldwide health phenomenon, therefore, cannot be blamed on all citizens' sense of responsibility and willpower. He blames the companies that provide the processed goods that cause such diseases and the governments that subsidise these crops, thus those who provide the 'means.'

The 'responsabilization' (Wakefield, Fleming, n.d.) of individuals over their own health is, in Chad Lavin's views (2013, quoted in Godrej, 2017, p. 907) "married to ideologies of healthism in which health is understood to be a product of our own choices" which denies the toxicity of food environments and unaffordability of certain habits. This illustrates the difficulty to balance empowering individuals to care for themselves and exercise "active citizenship" in their health (Godrej, 2017, p. 904) or 'responsibilize' them for it, in the presence or absence of favourable resources.

Medical and nursing researchers have aimed to measure and operationalize self-care agency (Carter, 1998, p. 195) in patient care for decades. All these methodologies serve health practitioners with a framework to assess a patient's degree of agency to care for themselves or to ask for help when needed. An interesting scenario would be to bring these methods into daily life and governmental policies, where individuals and communities assessed their means to access self-care practices, institutions acknowledged the presence or absence of 'conversion factors' to transform these into 'functionings' to achieve wellbeing (Robeyns, Byskov, 2020), and provided help when any of these pieces were missing.

These theories, however, assume that if the person is unable to care for themselves, that help may be available. However, the WHO acknowledges that self-care is "the ability (…) to promote health, prevent disease (…) and cope with illness with or without the support of a healthcare provider" (WHO, n.d). This is where the concept of accessibility comes into the debate, which we identify as the second main factor that may shape an individual or a community's opportunity to practice self-care in a capitalist Western context.

Accessibility

In the context of self-care, accessibility refers to whether self-care practices and information can be reached, obtained, or understood easily(Accessibility, n.d.). To measure whether self-care practices are accessible, we must identify the areas of an individual or collective's lives that must be cared for to survive and thrive.

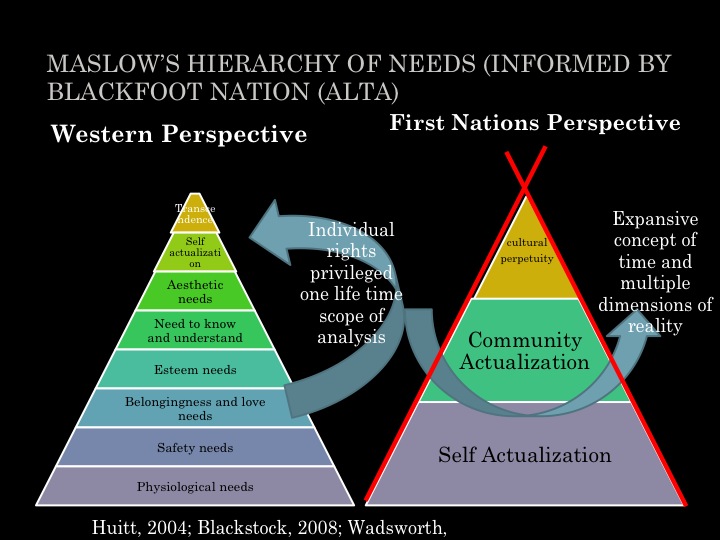

Due to the specificity of the context we present, Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs (Maslow, 1943) serves as a useful framework to identify the human needs that must be cared for. However, we must acknowledge the sources that Abraham Maslow borrowed from when writing his theory, which he failed to credit when publishing it. In the summer of 1938, Maslow visited the Siksika reserve in Alberta, USA, where members of the Blackfoot Nation shared their teachings (Ravilochan, 2021) with him. In his visit, he wanted to test the "universality of his theory that social hierarchies are maintained by dominance of some people over others" (Ibid., 2021). However, he saw that cooperation and inter-dependency were essential pillars to satisfying individual and collective needs in First Nations communities.

A graph made by activist and professor Dr. Cindy Blackstock (2008), a member of the Gitxsan tribe, illustrates the differences between Western narratives, based on Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, and Indigenous First Nations teachings on human needs (see Figure 2). It shows the concepts that Maslow took from the First Nations perspectives and rearranged to fit a Western narrative.

Figure 2. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs (Informed by Blackfoot Nation (Alta), illustration made by Dr. Cindy Blackstock (2008).

Figure 2. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs (Informed by Blackfoot Nation (Alta), illustration made by Dr. Cindy Blackstock (2008).

As seen in Figure 2, "Maslow believed that truly healthy people were self-actualizers because they satisfied the highest psychological needs" (Abraham Maslow, 2021). In agreeance with Foucault, he believed that working on the self is the ultimate step in achieving wellbeing, and something one works towards. In contrast, First Nations communities believe that self-actualization is an "innate" quality that "you spend your life living up to" (Ravilochan, 2021) and the base of an individual's life. Community actualization, as defined by Dr. Blackstock, is the "work of meeting basic needs, ensuring safety, and creating the conditions for the expression of purpose as a community responsibility" (2021) which differs from the isolating and 'responsibilizing' contemporary Western quests to fulfil basic physiological and safety needs individually and independently.

Maslow's theory (1943), importantly brings up the debate on "cultural specificity and generality of needs." The theory does not claim that these needs are ultimate for all cultures yet are more unifying and basic than other desires that differ from culture to culture. Considering that this investigation revolves around a Global North capitalist context, we may agree that having access to certain practices or conditions is deemed indispensable to being well. The following sections will focus primarily on the economic inaccessibility of certain self-care practices and their contemporary commodification.

Commodification of Self-Care: Colour & Design

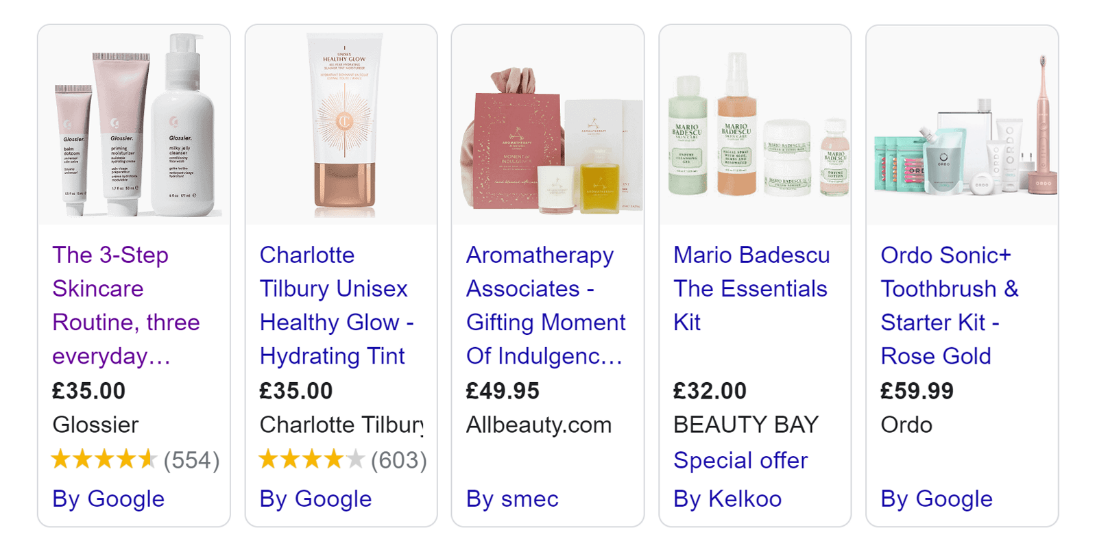

Upon searching for 'self-care' on Google Search, the ads that come up feature journals, candles, herbal teas, aromatherapy, skin care products and books, often in a beige, baby pink and mint green colour palette (see Figure 3) and with a "minimalist, sans-serif and streamlined" aesthetic (Carraway, 2019). According to Color Psychology, a website by cognitive psychologist Hailey van Braam (2021), mint evokes tranquillity, health, growth and wellness. Pink in Western cultures, connotes femininity, calmness, innocence and optimism, and beige, minimalism, simplicity and serenity. These products, their respective designs and marketing campaigns, provide "a childlike lightness that momentarily distracts from the grown-up problems of the everyday" (Carraway, 2019) of individuals that may be overworked in a capitalist context.

In consumer culture, commodification is the "economic and cultural processes through which objects [and activities] become commodities, and it is commonly held that these involve both the material production of the thing and the semiotic marking of it as a particular kind of thing" (Evans, Southerton, n.d.). The paradox of the self-care industry is that "it is a commercial enterprise (…) but the market [of these products] points to ills that conventional medicine alone can't seem to cure either" (Bari, Adeane and Corbett, 2020), explains academic Shahidha Bari. In a radio show on Radical Self-Care, experts question when the Western modern self-care movement became marketable and consumerist (Ibid., 2020).

Figure 3. Ads that appear upon Google searching 'self care' on an Incognito Window, featuring a specific colour palette.

Figure 3. Ads that appear upon Google searching 'self care' on an Incognito Window, featuring a specific colour palette.

Its origins are often tracked down to the Esalen Institute, a community retreat centre founded in 1962 California, where senior intellectuals experimented with 'Eastern' and 'Western' alternatives to health and the "human potential movement" (2020) began. André Spicer (2020), writer of The Wellness Syndrome believes that in this movement all humans had potential yet needed "the right techniques to unlock it", which draws a parallel with First Nations' perspectives on self-actualization. Due to its closeness to Silicon Valley, tech workers attended the courses and due to their influence these practices infused American culture.

Spicer explains that the movement lost sight of its origins and became much more about being "a more productive, competitive and ultimately, more marketable person" (2020). This coincides with the notion of contemporary capitalist societies where often "citizens' (…) moral autonomy is measured by their capacity for self-care" (Godrej, 2017, p. 907), therefore 'responsibilizing' individuals for their abilities to care for themselves to ensure their own productivity.

The Esalen's philosophy (Bari, Adeane and Corbett, 2020) seeks to fulfil the top level of Maslow's theory (1943), self-actualization. Therefore, the place that is seen as the seed of the Western contemporary self-care movement, if using Maslow's ideas as a reference, is only achievable by those whose basic needs are met, thus only available to a few privileged bodies.

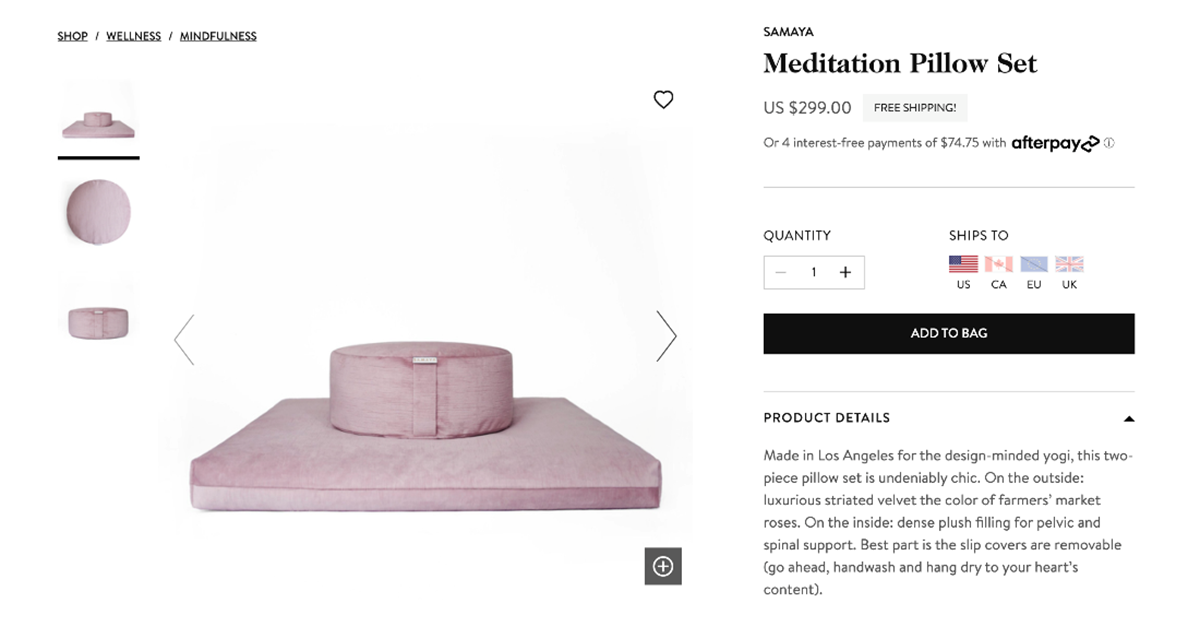

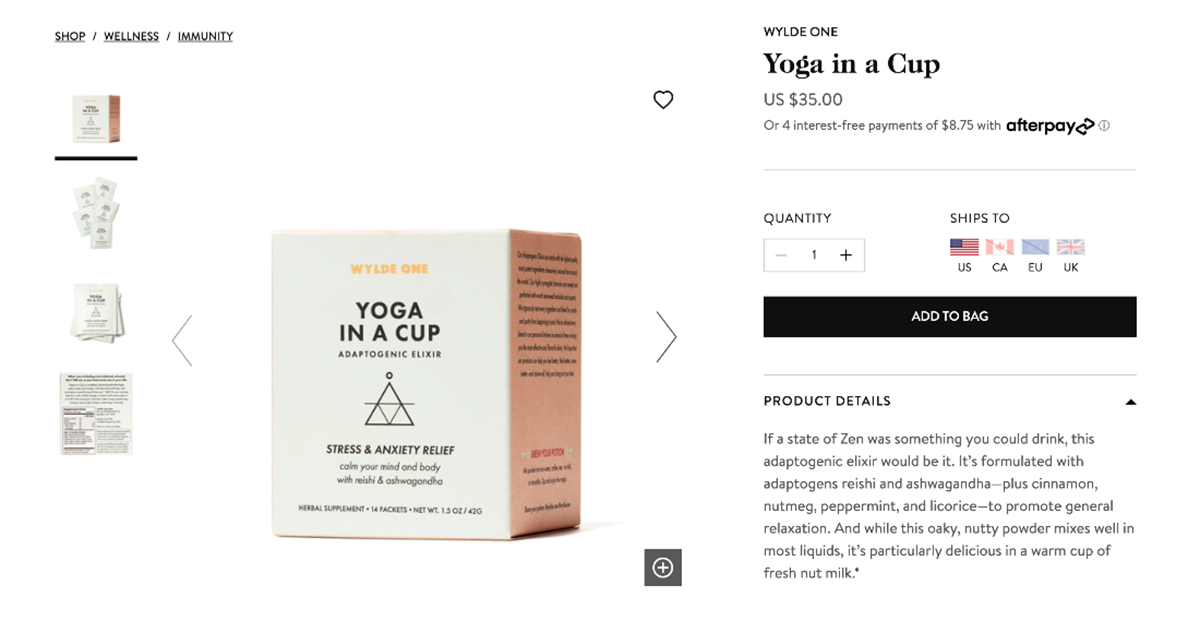

On a contemporary note, the commodification of self-care is seen when expensive brands exploit the self-care and wellness labels for profit. Well-known and controversial Goop, founded by Gwyneth Paltrow (Goop, n.d.) is an example of this. They state their intention to make "cutting-edge and mainstream science" accessible to more people (Ibid., n.d.), however, a brand with their price points (see Figures 4, 5) will not attract a large, wide audience, thus is not an example of an accessible platform and brand.

As mentioned earlier, there is certain colour and design characteristics that are common amongst contemporary products with the 'self-care' and 'wellness' labels. An example is the Meditation Pillow Set (see Figure 4), a product sold by Goop at a price point of $299. Made of velvet and plush fillings, this pink product targets "the [wealthy] design-minded yogi" (Goop, n.d.). The light pink, connoting calmness and femininity (van Braam, 2021), the rounded corners of the soft velvety shapes and the 'Mindfulness' classification of the product make this an object that is gendered and a commodity of the ancient 'Eastern' practice of meditation.

Elisa Albert and Jennifer Block recently wrote an opinion article in which they defend Goop's "other ways of knowing" (Albert, Block, 2020). They argue that, for centuries, women's traditional knowledge has been mocked and feared for challenging "the authorities" and for not being entirely provable. Goop's intention to take one's care into one's own hands can be empowering, in a medical context which historically has not prioritised women's health. However, with their high price tags they profit excessively off female empowerment and their elitist health-conscious costumers. Simultaneously, their target audience likely has access to healthcare and their quest may be one of conspicuous consumption 2 and exclusive optimisation of health, rather than one of self-care or wellness.

The person who purchases Goop products is most likely looking for a sense of relief, a temporary disconnection, a pleasant sensory experience, or a moment of comfort. If we define care as something we need and being well as being healthy in all its forms, classifying these products under the self-care and wellness labels is misleading. By promising a journey towards self-care, they commodify this practice, marketing it to fit a very specific demographic, a middle class or higher socioeconomic group, and making it a paid experience for those who want to "attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection" (Foucault, 1988, p. 18). This mission greatly differs from the concept of self-care that this investigation defends. The following section will explore the structures of care that are essential to one's wellbeing in the specific context we explore.

Figures 4, 5. These are some of products sold on the Goop website that feature the abovementioned colour palettes. They are expensive, minimalist and provide relief for ills such as pelvic discomfort and stress.

Figures 4, 5. These are some of products sold on the Goop website that feature the abovementioned colour palettes. They are expensive, minimalist and provide relief for ills such as pelvic discomfort and stress.

Structures of Care

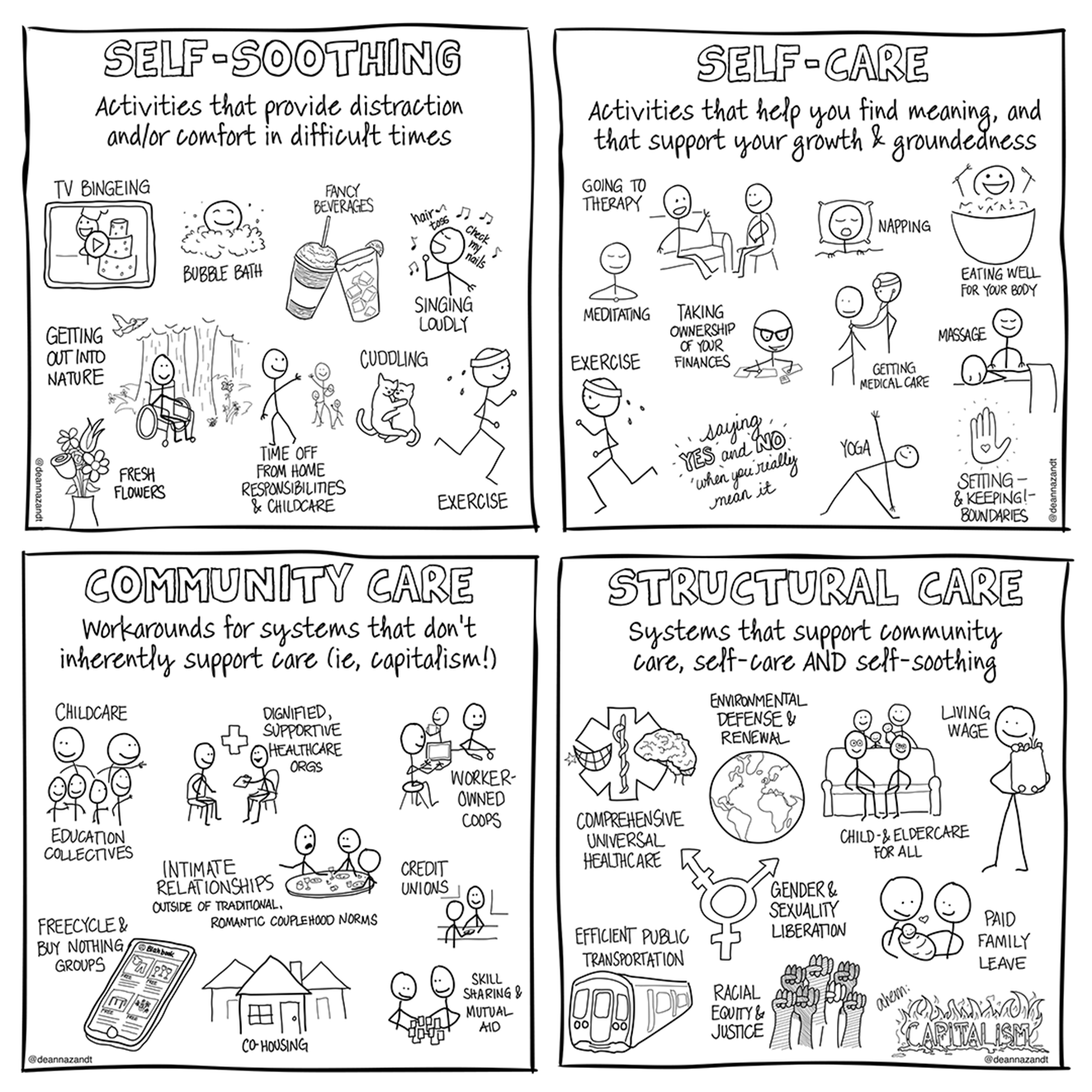

The Unspoken Complexity of Self-Care(Zandt, 2019) is a comic that explores the layers of care, from more personal and pleasure-seeking to structural (see Figure 6). Four levels are identified: self-soothing activities, self-care practices, community care and structural care. As mentioned in the introduction, there is an established rhetoric from many Western governments, healthcare practitioners and societies at large, that performing certain activities are necessary to being well (see Figure 1). In its essence, self-care consists in practising these activities consistently. However, awareness of this information is often not enough to partake in these actions. Having the most basic needs covered, such as access to clean water, stable housing, a warm space to rest and breathable air, will shape whether these practices can be attempted. These needs may "lie dormant, or [be] pushed into the background" (Maslow, 1943) until other needs are fulfilled.

Structural care may be defined as the utopia of care, the ideal systems that should exist in every region to ensure dignified living conditions for all. To the list we add public education, from preschool to university, and a justice system that is unbiased. Far from this ideal situation, there are many gaps in public systems which prevent care being attainable. Out of 195 countries in the world (Worldometer, n.d.), 117 offer universal healthcare to their citizens, which means that healthcare is available to more than 90% of these country's citizens (World Population Review, 2021). The remaining countries do not have public healthcare systems. At least half of the world's population still does not have coverage of essential health services (WHO, 2019). In these regions, healthcare is a purchasable, commodified service.

The self-care section of the illustration (see Figure 6) features "going to therapy" and "setting and keeping boundaries," (Zandt, 2019) which are often not professed by health authorities or communities as a way of being well yet, to many, may be essential to maintaining mental health. However, the WHO calculates that "countries spend on average only 2% of their health budgets on mental health", even though "1 billion people are living with a mental disorder." They also know that "for very US$ 1 invested in scaled-up treatment for common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety, there is a return of US$ 5 in improved health and productivity" (WHO, 2020). This quote synthesizes that governments or companies' incentive to invest on people's care is often about individuals becoming "more productive, competitive, and (…) more marketable" people (Bari, Adeane and Corbett, 2020), rather than ensuring a sense of wellbeing as a human need and right.

Another factor is the correlation between poverty and mental health issues. A study suggests that people living in UK households in the lowest 20% income bracket are two to three times more likely to develop mental health problems than those in the highest (Mental Health Foundation, n.d.). This statistic suggests that sustaining health is not only about personal responsibility, willpower and "internal narrative" (Bari, Adeane and Corbett, 2020), but is highly dependent on one's socioeconomic status. This will shape whether someone has the agency, the 'means' and the necessary 'conversion factors' to care for themselves.

These past chapters have looked at the two main factors that influence the opportunity to practice self-care, within a capitalist Global North system. From the obstacles and hardships to access essential care services, have stemmed, arguably, the most important care structures: community care initiatives. The following chapter will highlight examples of community, self-organised care projects that aim to offer dignified, free care to their collectives.

Figure 6. The Unspoken Complexity of Self-Care, an illustrated comic by Deanna Zandt that explores the different types of cares and needs (Zandt, 2019).

Figure 6. The Unspoken Complexity of Self-Care, an illustrated comic by Deanna Zandt that explores the different types of cares and needs (Zandt, 2019).

Self-Organised Collective Care

Throughout this investigation we have argued that the care of the self is essential to every human. Ideally, the means and adequate life circumstances should be facilitated by public systems of care. However, as seen, care is very often a privilege rather than a right. When discriminated against, using one's agency to care for the self may be a statement of autonomy, resistance, and self-preservation against a societal dynamic or governmental institution which systematically disfavours a group of people. Self-organised community care projects have risen from these gaps in these systems for decades.

Self-Care in Activism: La Serena & Black Lives Matter

Human rights defenders work in very vulnerable and dangerous positions. 304 defenders were murdered in 2019 alone, with the Americas being the deadliest places to be an activist (Front Line Defenders, 2019). Self-preservation in the context of human rights activism is a vital aspect of this work, which challenges "the idea of activism as selflessness" (New Tactics, 2010), and confronts the "Global North" idea of "self-care [as] disunited and individualist" (Pikara Magazine, 2019).

The Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Human Rights Defenders, also known as IM-Defensoras, (Presentación, n.d.) was founded in 2010 in response to the violence against these collectives. They connect activists from different organisations and social movements and create protection and solidarity networks. One of their projects is Casa La Serena, a temporary housing retreat in Oaxaca, Mexico, for the "recovery, healing, resting and reflection of women human rights defenders who face situations (…) that derive from the context of violence and patriarchal culture" (Casa La Serena, n.d.). The power of a Central American female initiative organising collective self-care retreats for human rights activists, a region in which doing that work can cost them their life, is deeply revolutionary. As Lorde said, self-care is an act of political warfare (Lorde, 1988), a war against those whose attacks on human rights they fight to defend. In caring for their integrity and wellbeing, they proclaim a war against those who threaten their lives and ensure their collective fight is sustained long-term.

An engagement in the care of the self may be considered a "prerequisite" (Godrej, 2017, p. 914) to engaging in activism. The Black Lives Matter toolkit on 'Healing In Action' outlines the importance of "healing justice" as an essential aspect of "direct action" (Black Lives Matter, n.d.). This free resource lists bodyworkers, counsellors, food drop offs, therapists for Queer and Trans activists, acupuncturists, and other practitioners as forms of community care to support activists. This indicates that Black Lives Matter's understanding of care is integral, collective, "transformative" and in itself a fight against "violence and systems of oppression" (Black Lives Matter, n.d.). Not only is collective self-care essential in being present and healthy in direct action, but also in sustaining social movements in the long run, which for as long as human rights are violated, will need to exist.

Health Clinics: Black Panther Party & Zapatistas

In 1966, the Black Panther Party (known as the BPP) was founded in Oakland, California (BlackPast, 2020). It fought racial inequality, violence and police brutality against Black people and People of Colour. In 1983, some kilometres away, in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (also, EZLN) was founded in response to years of oppression of indigenous communities and the recent governor's increased "military repression in the face of indigenous rebellion" (Schools for Chiapas, n.d.). On January 1st, 1994, the Zapatistas declared war on the Mexican government. They seized government buildings and occupied acres of private land.

Regardless of the geo-cultural differences, these movements rose from the repression of their respective governments and societies and the historical systemic discrimination to their communities. Looking at the Black Panther's Peoples' Free Medical Clinics (BlackPast, 2020) alongside the Zapatista-organised regional health centres (Schools for Chiapas, n.d.) serves as a fascinating example of community self-organisation of care.

On the day of their military uprising, the EZLN proclaimed their "First Declaration of War from the Lancondon Jungle" (Declaration of War, 1993), which stated their struggles and demands. Similarly, the Black Panther party's "Ten Point Platform and Program" (National Archives, n.d.) served as a manifesto of their rights. Their respective manifestos coincided in their fight for the most basic needs and rights, which were and still are being repeatedly violated: employment, housing, education, freedom, justice and peace, amongst others.

The BPP started the Peoples' Free Medical Clinics in 1968 (BlackPast, 2020). Any group that wanted to call itself a Black Panther chapter was required to sell copies of their newspaper and to open a health clinic (Bari, Adeane and Corbett, 2020). In 2003, the EZLN cemented their autonomy through the creation of Caracoles, political and cultural self-governing municipalities (Schools for Chiapas, n.d.). Since then, they have created free health centres to improve the life of the indigenous communities of Chiapas. Both communities chose trusted local volunteers to staff the clinics, pharmacists, lab technicians (BlackPast, 2020) and trained 'healthcare promoters' (Schools for Chiapas, n.d.).

These movements' most revolutionary feats were the BPP's national screening program for sickle cell anaemia, a "genetic disease mainly affecting people of African ancestry," largely neglected by the US government (BlackPast, 2020) and the Zapatistas' fully equipped centres with hospital beds, operating rooms, vaccination programs and pharmacies that offer traditional herbal medicines and patent medicines (Schools for Chiapas, n.d.).

The BPP's clinics were harassed by health inspectors and police raids and gradually started closing (BlackPast, 2020). Similarly, the Zapatistas autonomous municipalities are repeatedly subject to harassment by the state and federal police, with incarcerations, deportations and murders happening for decades (Schools for Chiapas, n.d.).

These are exemplary cases of community self-organisation to confront oppression and segregation. In the absence of accessible, non-biased medical care, collective care structures are crucial for survival. The harassment exercised by the police and governments upon witnessing self-organisation proves that the notion of self-determination over their health threatens the order of these systems, which had for decades systematically marginalized these communities. These collective care structures are an example of radical resilience against the very discriminatory systems that 'responsibilize' these communities for their own healthcare.

COVID-19: Isolation & Solidarity

During this pandemic, care, wellbeing, and health in all its forms have come to the forefront of political debates and personal discussions. In the face of such adversity, self-care as collective care and solidarity have risen to sustain health. At the beginning of the outbreak in China, "the whole society self-mobilized in a way never seen before, forming social networks of support" (You, 2020). Drivers offered transportation to healthcare workers, hotel owners offered their rooms, and restaurants offered free meals. Gradually, as the virus spread, these displays of inter-dependent collective care started to appear in many other places.

With social distancing and stay at home measures, communicating and organising online has become the norm. An example of this is a database of all mutual aid groups around the world (Mutual Aid Wiki, n.d.), currently 5770. The site is run by volunteers, has open-source code and any community can add their group onto the map. Mutual aid groups have risen in the spirit of solidarity, to help neighbours navigate the pandemic, especially those in vulnerable positions. Providing care for health workers has also been and still is critical, with people creating networks to make handmade PPEs (Blackall, 2020) for those in the most dangerous positions due to shortage.

The night of March 31st, 2020, a library was inaugurated in the biggest temporary field hospital in Spain (Marquina, 2020). IFEMA, which used to be a fair pavilion, became a field hospital a few days before that night, to manage the overwhelming amount of critical coronavirus cases in Madrid. Ana Ruiz, a nurse of the medical emergency unit, collected many of her books and created a small library for patients to entertain themselves, to which many other health workers added their donations. This library was given the name Resistiré after a song that became an anthem of the pandemic, which translates into "I will resist." This initiative recognises that in a situation of such emergency, reading, nurturing one's mind and entertaining oneself are also important layers of care, as well as acknowledging the patient's humanity and needs.

In cases of desperation and urgency, the best of humans can come out. The notion of care as a form of sustaining health and preventing disease (WHO, n.d.) may not be enough in the future. We may be entering an era which recognises that care, of the self and of others, must be integral, taking into consideration one's living situation, mental health, abilities, means and needs.

Conclusion

This investigation has travelled through several realistic and ideal iterations of self-care. It has explored self-care as a series of actions that require power and ability, as an exercise of self-governance that is both freeing and destructive, as a practice of ethics, as an exercise of good citizenship, as inaccessible in its most consumerist manifestations, as a necessary practice to survive against discrimination and as a form of civil responsibility and solidarity.

In the first paragraph of this essay, we defined self-care as providing for oneself what oneself needs. We, then, asked: What do we need? Throughout the research, there are certain human conditions that have been deemed necessary: food, clean water, safe housing, clothing, breathable air, employment, access to healthcare, public education, rest, freedom in any of its forms, independence, a support system and absence of violence and oppression. In a utopia of a care-centred society, everyone would have these needs fulfilled because the public structures that provide them would be in place and there would be no unjust socio-historical powers and dynamics than impede their fulfilment. Rather than self-care being something you earn and work towards, it would be a right facilitated by the public sector. Everyone would have the space, freedom, and time to consciously mould their self-care practices to their own personal and collective desires, perhaps in a more experiential, transcendental, and pleasure-seeking manner, like contemporary alternative health experiences.

In reality, there are systems of oppression which shape whether each person's needs are met. For as long as these systems are standing, there will be extreme disparity in each person's care for themselves. As Natalia Mehlman Petzrela (2016) says, "the narrative of wellness over the past 40 years is as much about the activism of the disenfranchised as about the forward march of narcissism." Self-care will continue to be simultaneously a series of individual, sense-stimulating purchases that tend towards over-consumerism, a search for disconnection amidst the stresses of daily life and a fight for freedom, survival and resilience against injustice and violence.

As present citizens of Global North countries, our self-care projects must be a fight against the status quo. We must interrupt the self-sufficient and individualistic quests for being well, and practice care with a spirit of solidarity, attention for others, sharing and asking when needed, compassion and humanity, inspired by First Nations, Zapatista and Black Panther communities, and many other collectives.

The field of design can contribute to this fight by highlighting, working for and spreading information about socially engaged care initiatives, such as mutual aid groups, non-profit organisations and socio-political movements, and steering away from the commercial and consumerist fields that continue to present the journey towards 'self-care' through elitist goods and activities. As designers, we can learn from the horizontal, cooperative strategies in social justice collectives and translate them into creative projects and workplaces, thus challenging the role of the designer as an individual problem-solver and aiming for a multi-faceted, accessible, and collaborative way of producing visual culture.3

Bibliography

Abraham Maslow (2021) in Encyclopedia Britannica [online] Available at: \<https://www.britannica.com/biography/Abraham-H-Maslow\> [Accessed: 2 January 2021]

Academia, (n.d.), Farah Godrej. Available at: \<https://ucriverside.academia.edu/FarahGodrej\> [Accessed: 11 January 2021]

Accessibility, (n.d.), in Cambridge Dictionary [online] Available at: \<https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/accessibility\> [Accessed: 11 January 2021]

Albert, E., Block, J. (2020) 'Who's Afraid of Gwyneth Paltrow and Goop?', The New York Times, 3 February. Available at: \<https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/03/opinion/goop-gwyneth-paltrow-netflix.html\> [Accessed: 23 January 2021]

Bari, S., Adeane, A., Corbett, J. (2020). Radical Self-Care (October 2020), BBC Analysis [radio]. Available at: \<https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000k7k0\> [Accessed: 23 November 2020]

Black Lives Matter, (n.d.), Healing in Action. [pdf] Available at: \<https://blacklivesmatter.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/BLM_HealinginAction-1-1.pdf\> [Accessed: 5 January 2021]

Blackall, M. (2020) 'The volunteers making PPE on the homefront for UK health worlers', The Guardian, 23 April. Available at: \<https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/the-volunteers-making-ppe-on-the-homefront-for-uk-healthworkers-coronavirus\> [Accessed: 22 January 2021]

BlackPast (2020). Black Panther Party's Free Medical Clinics (1969-1975). [online] Available at: \<https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/black-panther-partys-free-medical-clinics-1969-1975/\> [Accessed: 5 January 2021]

Blackstock, C., 2008. Maslow Hierarchy of Needs (Informed by Blackfoot Nation). [image] Available at: \<https://lincolnmichel.wordpress.com/2014/04/19/maslows-hierarchy-connected-to-blackfoot-beliefs/\> [Accessed: 3 July 2021]

Care, (n.d.), in Cambridge Dictionary [online] Available at: \<https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/care\> [Accessed: 2 January 2021]

Carraway, K. (2019), 'When Did Self-Help Become Self-Care?', The New York Times, 10 August. Available at: \<https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/10/style/self-care/when-did-self-help-become-self-care.html\> [Accessed: 21 November, 2020]

Carter, P. (1998) 'Self-Care Agency: The Concept and How It Is Measured', Journal of Nursing Measurement, 6(2), pp. 195-207. Available at: \<https://www.researchgate.net/publication/13260372_Self-Care_Agency_The_Concept_and_How_It_Is_Measured\> [Accessed: 3 January 2021]

Casa La Serena, (n.d.) Iniciativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos. [online] Available at: \<https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/sites/default/files/global\_analysis\_2019\_web.pdf\> [Accessed: 20 January 2021]

Declaration of W__ar, (1993) [Broadcast]. 31 December, 1993. Available at: \<http://archive.oah.org/special-issues/mexico/zapmanifest.html\> [Accessed: 5 January 2021]

European Public Health Alliance (2019). What are 'food environments'? [online] Available at: \<https://epha.org/what-are-food-environments/\> [Accessed: 20 January 2021]

Evans, D., Southerton, D. (n.d.) 'Commodification' in Encyclopedia of Consumer Culture. Available at:

\<http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/consumerculture/n83.xml\> [Accessed: 5 January 2021]

Feeding Frenzy (2013) [film] Directed by Kate Geis, Rebecca Rideout and Sut Jhally. Available through: Kanopy [Accessed: 11 January 2021]

Foucault, M. (1988) Technologies Of The Self. Edited by L. H. Martin, H. Gutman and P. H. Hutton. United States of America: The University of Massachusetts Press.

Foucault, M., Rabinow, P. (1997). Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth. Translated from French by R. Hurley et al. New York: The New Press. pp. 281-301

Front Line Defenders, (2019). Front Line Defenders Global Analysis 2019. [pdf] Available at: \<https://www.frontlinedefenders.org/sites/default/files/global\_analysis\_2019\_web.pdf\> [Accessed: 20 January 2021]

Gilabert, P., O'Neil, M. (2019) 'Socialism', in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: \<https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/socialism/#SociCapi\> [Accessed: 25 December 2020]

Gilbert, S. (2020) 'The Retrograde Shame of The Biggest Loser', The Atlantic, 29 January. Available at: \<https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/01/the-retrograde-shame-of-the-biggest-loser/605713/\> [Accessed: 12 January 2021]

Godrej, F. (2017) 'Gandhi, Foucault, and the Politics of Self-Care', Theory & Event, 20(4), pp. 894-916. Available at: \<https://muse.jhu.edu/article/675625\> [Accessed: 4 January 2021]

Goop PhD, n.d. Goop [online] Available at: \<https://goop.com/goop-phd/\> [Accessed: 20 January 2021]

Goop (n.d.) [online] Available at: \<https://goop.com/uk\> [Accessed: 21 January 2021]

Harvard Women's Health Watch (2017) What is vaginal steaming?[online] Available at: \<https://www.health.harvard.edu/womens-health/what-is-vaginal-steaming\> [Accessed: 17 January 2021]

Hylland Eriksen, T., n.d. What's wrong with the Global North and the Global South?. [online] Global South Studies Center Cologne. Available at: \<https://web.archive.org/web/20161009141000/http:/gssc.uni-koeln.de/node/454\> [Accessed: 1 July 2021]

J. Phillips, R., 2014. Conspicuous consumption. [online] Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: \<https://www.britannica.com/topic/conspicuous-consumption\> [Accessed: 1 July 2021]

Kisner, J. (2017) 'The Politics Of Conspicuous Displays Of Self-Care', The New Yorker, 14 March. Available at: \<https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-politics-of-selfcare\> [Accessed: 4 January 2021]

Le Grand, J. and New, B. (2015) Government Paternalism: Nanny State or Helpful Friend?. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Lorde, A. (1988) A Burst of Light and Other Essays, 2nd edn, Ixia Press, New York.

Maier, J. (2020) 'Abilities', in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: \<https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/abilities/\> [Accessed: 2 January 2021]

Marquina, J. (2020) Nace una biblioteca en el mayor hospital de campaña de España: La Biblioteca IFEMA. [online] Available at: \<https://www.julianmarquina.es/nace-biblioteca-mayor-hospital-la-biblioteca-ifema/\> [Accessed: 23 January 2021]

Maslow, A. H. (1943) A Theory of Human Motivation, Psychological Review, 50(4), pp. 370-396. [online] Available at: \<http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Maslow/motivation.htm\> [Accessed: 2 January 2021]

Mental Health Foundation (n.d.) Mental health statistics: poverty [online]Available at: \<https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/statistics/mental-health-statistics-poverty\> [Accessed: 17 January 2021]

Mutual Aid Wiki (n.d.) [online] Available at: \<https://mutualaid.wiki/\>[Accessed: 21 January 2021]

National Archives (n.d.) The Black Panther Party. [online] Available at: \<https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power/black-panthers\> [Accessed: 20 January 2021]

New Tactics (2010) Self-Care for Activists: Sustaining Your Most Valuable Resource [online] Available at: \<https://www.newtactics.org/conversation/self-care-activists-sustaining-your-most-valuable-resource\> [Accessed: 20 December 2020]

Oxford Reference. n.d. Visual culture. [online] Available at: \<https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803120056937?rskey=peZQs4&result=16\> [Accessed: 1 July 2021]

Petrzela, N. M. (2016) 'When Wellness is a Dirty Word', The Chronicle of Higher Education, 1 May. Available at: \<https://www.chronicle.com/article/when-wellness-is-a-dirty-word/\> [Accessed: 21 November 2020]

Pikara Magazine (2019) Autocuidado y cuidado colectivo, prácticas de resistencia en tiempos violentos. [online] Available at: \<https://www.pikaramagazine.com/2019/11/autocuidado-cuidado-colectivo-practicas-resistencia-tiempos-violentos/?fbclid=IwAR0sS6ORm0VgtM4sRp22Ipi1S3hHl-kRTMPfmN0Ptjz4UoDJjAqZ-wNeR94\> [Accessed: 10 December 2020]

Presentación (n.d.) Iniciativa Mesoamericana de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos. [online] Available at: \<https://im-defensoras.org/trayectoria/\> [Accessed: 20 January 2021]

Ravilochan, T., 2021. The Blackfoot Wisdom that Inspired Maslow's Hierarchy. [online] Resilience. Available at: \<https://www.resilience.org/stories/2021-06-18/the-blackfoot-wisdom-that-inspired-maslows-hierarchy/\> [Accessed: 1 July 2021]

Robeyns, I., Byskov, M. F. (2020) 'The Capability Approach', in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: \<https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/capability-approach/\> [Accessed: 10 January 2021]

Schlosser, M. (2019) 'Agency', in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: \<https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/agency/\> [Accessed: 24 December 2020]

Schools for Chiapas (n.d.) Community-Based Education for Health. [online] Available at: \<https://schoolsforchiapas.org/advances/health/\> [Accessed: 5 January 2021]

Schools for Chiapas (n.d.) Zapatista Timeline. [online] Available at: \<https://schoolsforchiapas.org/teach-chiapas/zapatista-timeline/\> [Accessed: 5 January 2021]

Self Care Forum. 2021. Self Care Week. [online] Available at: \<https://www.selfcareforum.org/events/self-care-week/\> [Accessed: 1 July 2021]

van Braam, H., 2021. [online] Color Psychology. Available at: \<https://www.colorpsychology.org/\> [Accessed: 3 July 2021]

Wakefield, A., Fleming, J. (n.d.) 'Responsabilization', in The SAGE Dictionary of Policing. Available at: \<https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-dictionary-of-policing/n111.xml\> [Accessed: 10 January 2021]

Wells, T. (n.d.) Sen's Capability Approach, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy [online] Available at: \<https://iep.utm.edu/sen-cap/#H1\> [Accessed: 15 January 2021]

WHO (2019) Universal health coverage. [online] Available at: \<https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight\> [Accessed: 5 January, 2021]

WHO (2020) Obesity and overweight. [online] Available at: \<https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight\> [Accessed: 5 January, 2021]

WHO (2020) World Mental Health Day: an opportunity to kick-start a massive scale-up in investment in mental health__. [press release] 27 August. Available at: \<https://www.who.int/news/item/27-08-2020-world-mental-health-day-an-opportunity-to-kick-start-a-massive-scale-up-in-investment-in-mental-health\> [Accessed: 12 January 2021]

WHO (n.d.) What do we mean by self-care? [online] Available at: \<https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/self-care-interventions/definitions/en/\> [Accessed: 12 December 2020]

Wikipedia (2021) Global North and Global South. [online] Available at: \<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global\_North\_and\_Global\_South\> [Accessed: 1 July 2021]

World Population Review (2021) Countries With Universal Healthcare 2021. [online] Available at: \<https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-with-universal-healthcare\> [Accessed: 23 January 2021]

Worldometer (n.d.) Countries in the world. [online] Available at: \<https://www.worldometers.info/geography/how-many-countries-are-there-in-the-world/\> [Accessed: 23 January 2021]

You, M. (2020) 'The social support networks stepping up in coronavirus-stricken China', Open Democracy, 17 March. [online] Available at: \<https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/social-support-networks-springing-coronavirus-stricken-china/\> [Accessed: 23 January 2021]

Zandt, D. (2019) The Unspoken Complexity of "Self-Care" [online] Available at: \<https://blog.usejournal.com/the-unspoken-complexity-of-self-care-8c9f30233467_\>\_ [Accessed: 23 November 2020]

- 'Global North' is a term used increasingly in the last decades to refer to a grouping of countries with similar socioeconomic and political landscapes (Global North and Global South, 2021). 'Global North' is often used interchangeably to 'developed' or 'Western' countries and does not refer necessarily to the geographical North, as many countries in the 'Global South' are in the Northern Hemisphere. The term 'Global North' includes "areas such as Australia, Canada, the entirety of Europe and Russia, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, and the United States " (Global North and Global South, 2021). The 'Global South' and the 'Global North' "distinguishes not between political systems or degrees of poverty, but between the victims and the benefactors of global capitalism" (Hylland Eriksen, n.d.).↩

- Conspicuous consumption is a "term in economics that describes and explains the practice by consumers of using goods of a higher quality or in greater quantity than might be considered necessary in practical terms. The American economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen coined the term (…) The concept of conspicuous consumption can be illustrated by considering the motivation to drive a luxury car rather than an economy car. Any make of car provides transport to a destination, but the use of a luxury car additionally draws attention to the apparent affluence of the driver" (J. Phillips, 2014).↩

- Visual culture is defined as the "visual forms and practices within a society, including those of everyday life, popular culture, and high culture, together with the processes of production and consumption or reception associated with them. This includes all visual media (visual art, photography, film, television, posters, etc.)" (Visual culture, n.d.).↩