Synopsis

The script is divided into four parts. Each part analyses the major question of how the perception of reality can be distorted with cinematographic means. After each part the reader will find different coloured pages with the director’s remarks, summarizing the ideas and inspirations that went into writing the script and directing the short film. Director’s remarks are written in a relaxed manner as if it was a casual conversation between the filmmaker, screenwriter and viewer. The short film ‘Unreal Realities’ can be viewed and equally enjoyed without the complimentary publication. However, not only the script but also the director’s remarks let the viewer peek into the deeper and less tangible concepts of the aforementioned theme.

In part one of the script, the viewer is presented with a memory, an artefact from the past. Travel through time and space is possible with the power of memory. The recollection of the memory becomes perception and perception of the image becomes recollection. The memory is transformed in this cycle. The more memories are introduced, the more transformations happen at the same time. Manipulation of the viewer’s perception happens throughout the film with the changes of frames, repetition of the image, repetition of the rhythm and when stories interconnect with each other.

In part two we are forced to question – is reality real? Reality is sculpted of our perception which is shifting every second. One’s identity is not different in this case. It is always changing while only a few solid fragments stay in the same place and/or form.

In part three the repetition is discussed to be a tool to distort the perception of reality. It works contrary to its initial purpose, instead of creating meaning it retracts it and stretches the shot’s timeframe. Another concept examined in part three is embodiment. The shots of facial features shown together conceptualize the embodied mind.

In part four, the term ‘collective creativity’ is examined. The short film ‘Unreal Realities’ is just a catalyst for the ideas to be developed outside of the artist’s mind, in the world inhabited by the viewers. The word ‘viewer’ does not fit in this context but for the lack of a better term, it is used throughout the script. The viewer is considered to be an active participant, equally creating the meaning.

Following these pages, one will find the original script for the film ‘Unreal Realities’ (dir. Beatrice Keniausyte) complimented with director’s remarks.

Part 1

A monologue is carried through part 1. Person walks in the shot from the left side, sits on the stool and concentrates to start the monologue.

(NARRATOR 1)

EXTREME CLOSE UPS OF NARRATOR’S 1 FACE.

FEATURES: LIPS, EYES, EARS, NECK. BACKGROUND IS WHITE. CLOSE UPS OF NARRATOR’S HAND ON THE LAP AND LEGS ON THE STOOL.

NARRATOR 1

(slow manner)

It was cold and heavy, its solitary, mesmerizing crystal was shimmering in the daylight. Embedded in an antique, golden setting, it seemed enchanted, all it took was one glance and you could easily get lost in its captivating beauty.

Its lengthy oval, lilac gem was glittering and reflecting the sunbeams with each and every single feasible color. You could sense the strength pulsing from the crystal.

(emphasis)

It was a gift from the past.

(relaxed)

The kitchen was terrifyingly cold. Greasy yellow stains on the walls seemed like drawings made by a modernist painter, who expressed his emotions by throwing a huge piece of minced meat into the pan with hot oil splashing on the walls. The smell has grown into this room.

(emotionally)

Eew, I hated that smell.

(relaxed)

Although even this ugly kitchen could not diminish my love for the time spent there. My grandma would wrap me in a blanket and with a hot cup of lemon tea in her hand she told me stories of her life. I vividly remember, as if that was mine, rather than my grandmother’s memories told every evening, how being the youngest child in the family, she sold various clay figurines at a train station. She would sit behind her tiny wooden table and observe the passengers getting in and out of the trains while guessing what their journeys might have been like. With her huge popped eyes she tried to catch passengers’ attention and pressure them into buying the figurines, not because they needed them, just out of pure pity. Even a short glimpse towards her gave hope of a possible customer and a few extra pennies for dinner.

(excited)

Oh, and the stories that passengers would tell! It seemed that she had one in her pocket for every evening for the rest of my life. Or her life, to be precise.

(relaxed)

However, I have always wondered about this woman, who was part of every single story, neither young nor old, looking straight through the train window and scanning the surroundings. There was always a cardboard, square box in her hand.

NARRATOR 1

Despite how badly I wanted to ask her, what is so precious she has in that box, I couldn’t leave my figurines. And no matter how much I popped my eyes to grab her attention, she would never leave the train.

It belongs to you now - declared my grandma, once she put the cold object in my open hand and closed my fingers.

-END OF PART ONE-

Director’s remarks for part one

I have been writing these remarks ever since I had an idea for the story, up until we finished the final version of the script. Do not be alarmed by the inconsistency of my thoughts as I added paragraphs and parts as layers to explain the depth of the work created.

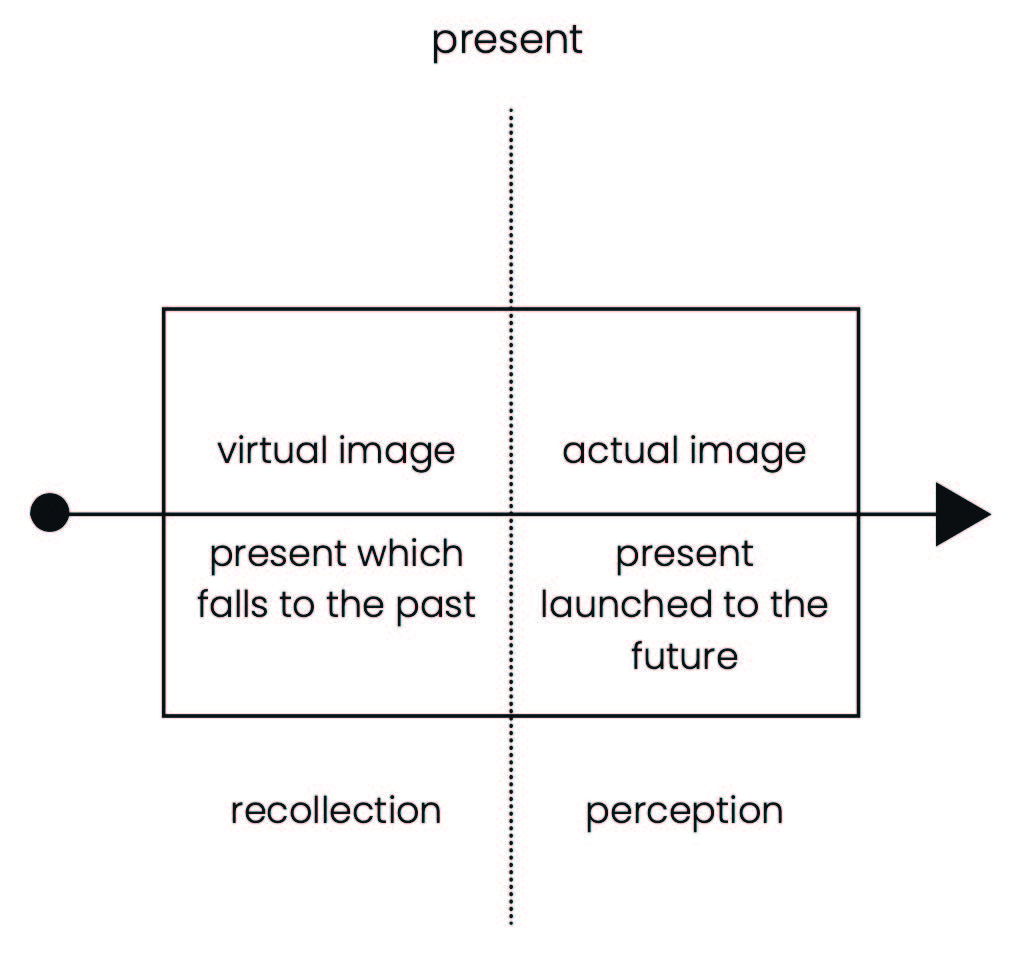

In part one we create a memory of the ring, an artefact from the past which chases the viewer to the very ending – part four, where all the stories meet. It reminds me of the term ‘crystal image’ (Deleuze, 1989) which is a unit of an actual image and its virtual image, in the concept of time. The actual image represents the present that is launched towards the future, while the virtual image represents the present which falls to the past. This coexistence of present and the past establishes new terms such as perception and recollection which occur at the same moment. By presenting the viewer with this artefact of a ring we mix up the actual image with its virtual image and the perception of the image becomes recollection and vice versa – recollection becomes perception. I will draw a scheme and stick it to this piece of paper, so it will be clear what I mean (figure 1). So the question arises – is the ring even real and existent? Maybe a crystal image is nothing more than a memory. We can go even deeper – what if this memory is fake? The box in the lady’s hands – there’s something there. Or it is supposed to be something there. What if it’s empty? Can we imagine the pure nothingness? French film-maker, theorist and critic Jean Mitry states clearly that this is impossible (Mitry, 2000). That’s why here I hope that the viewer will fill in the void of nothingness with the memory. The memory of the ring, to be precise.

The memory of the past is a gift. It is how we preserve ourselves and create our own identity. The memory is embedded in the smell of different odours in the kitchen, the view of the stains or sound of splashing oil, or even the touch of a fuzzy blanket. According to J. Mitry ‘When one thinks of the chair, one does not visualize an “image-chair” which is retained by memory. One visualizes the “reality-chair”, via the memory of it.’ (Mitry, 2000). Again, at the end of part one, we are playing with the notion of visualization via memory. Grandma is placing the cold object. The viewer assumes it must be a ring. But what was then in the box? It was a ring, surely – the viewer would say. The assumed reality mixes up with the one being told and with the one that’s is already a memory, a viewer’s memory. It becomes nothing other than a distortion, a true mise en abyme.

A similar mix up should happen in editing. In French philosopher’s Jacques Ranciere’s talk at the Centre National de la Photographie, he discussed how meaning is both created and retracted at the same time; the link is ensured and undone in cinema through images, text and sound (Ranciere, 2002). Although we do not specify the gender of the speaker in part one, I have imagined the person to be female. Therefore, I have thought of using a male’s voice and contrasting it with the image of a female. This action would allow us to create a link to the story being told from a female perspective and undo it at the same time with the contrasting sound.

I changed my mind. The mix up of the voices is an awful idea. I will manipulate with an image and with a rhythm. Recently, I have seen this amazing film (dir. Perretta, 2019) titled ‘The Destructors’ (figure 2). The usage of the rhythm blew me away! It created tension and manipulated the viewer's emotions. Manipulation of reality. Manipulation of people. I would like them to question, what has just happened while walking out of the screening. To question the memories we have, to question the reality we live in, the time and space we experience with our bodies and minds.

Shooting the film I am not planning to show the locations. The main centre of attention should be the monologue and dialogue later in the very end. However, I would leave a vivid description of the kitchen. It lets us travel through space and time – from the kitchen in the protagonist’s childhood to the train station of grandmother’s early days to the present of the viewer, wherever that would be.

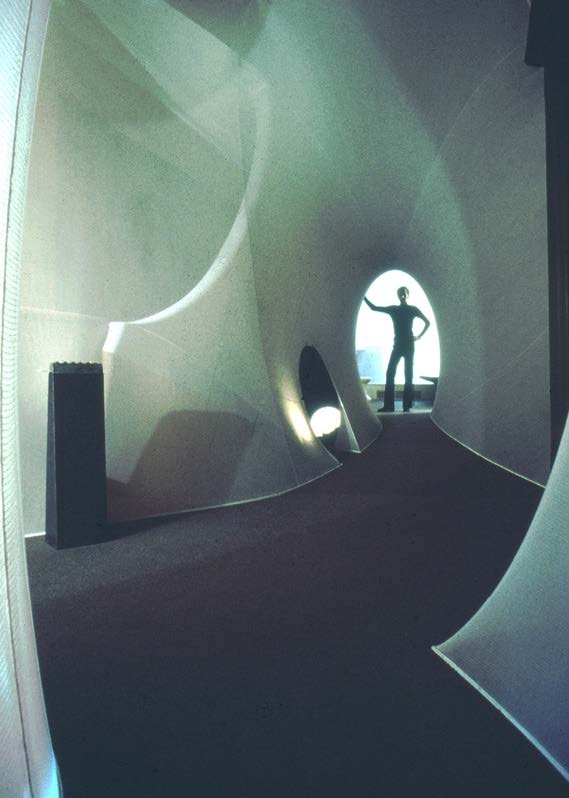

Lithuanian-American artist Aleksandra Kasuba created tensile fabric structures in her installations (figure 3) which enables us to experience the same journey and lets viewers wonder inside them. We are going to stretch and later compress the time the same way Kasuba does, only in the film form.

Part 2

The monologue is carried through part 2. Person walks in the shot from right side, sits on the stool and concentrates to start the monologue.

(NARRATOR 2)

EXTREME CLOSE UPS OF NARRATOR’S 1 FACE

FEATURES: LIPS, EYES, EARS, NECK. BACKGROUND IS WHITE. CLOSE UPS OF NARRATOR’S HAND ON THE LAP AND LEGS ON THE STOOL.

NARRATOR 2

(disgusted)

I am exactly forty years and twenty-two minutes old. Half of my life slipped away in this room. In this little, dusty and substandard office. The whole place even smells of misery. There was only one creaky window here, with white, at some point, curtains and a broken handle.

Though the room was meant for at least ten employees, the furniture here consisted only of three suspiciouslooking, plastic chairs situated around an old splintered table. All the walls looked like some poor soul hopelessly but persistently painted over dirt marks and mould, as if they were some awful drawings on canvas. Above one of the chairs, next to the door, there was an old photograph of one of those gigantic and heavy locomotives from the early nineteen hundreds.

(elated)

Trains have always fascinated me. Consistently on a schedule. Traversing through countless locations, forever sharing new stories with one another.

The web of trains is immaculately complicated, rhythmically passing villages, cities, countries and continents, rivers and lakes, meadows and lands, holding so many emotions and still… perpetually on time. Invariably prepared to leave the station and head from one to another distant point in time.

(ecstatic)

Whenever I sat foot in this room, I instantly felt down, as if some despairing force was filling up my body. That was a little paradox, knowing how much I adored trains when I was a kid. Although, I remember exactly when my perception of this space changed. One bright, but rainy morning around five a.m. I entered the office. I sat down at the table, double checking the wooden surface for splinters, and began preparing some documents.

Suddenly I noticed something moving in the corner of my eye, I was here alone. Intrigued, I slowly turned my head around. On my left side, on one of those terrible whiteish walls, there were three sunbeams, dancing and circling around each other. At first, I thought that it was just the sun shining through the window covered in droplets, but it was far too colorful and unprecedented.

(imitation)

I gasped out loud.

(faking)

I was not usually the type to fall in awe when it comes to pretty things but this was different. I had never seen so many bright, yet delicate colors in such a hypnotizing configuration. It looked like a light mosaic.

All of this was a matter of three, maybe four seconds, the beautiful beams were gone as suddenly as they appeared.

NARRATOR 2

Your ticket please, Ma’am.

NARRATOR 2

Without a word, she took out a long piece of paper and handed it to me.

NARRATOR 2

All good to go!

NARRATOR 2

The train took off.

-END OF PART TWO-

Director's remarks for part two

From Plato to Descartes, we read about dualism and dualistic thinking as if it is the only way of seeing and perceiving the world. Post-structuralist thinkers such as Jacques Derrida (Lawlor, 2019) argue the question of duality. Similar arguments can be spotted in independent film-maker’s Anne Charlotte Robertson’s ‘Five Year Diary’. It is an extremely large piece of a highly autobiographical film. In Robertson’s ‘Five Year Diary’ we can see the blurred distinction of self and other, past and present, human and non-human. The conscious and the unconscious are merged into one flow of visual and aural (audible) information. In Reel 22 she sets up lights in the morning, in order to film her lover, sleeping calmly in bed. The camera follows the movements of an unconscious body and little ticks of the fingers. Robertson distinguishes her conscious body and mind and her lover’s unconscious body. This short scene explores the conscious and the unconscious, while the camera is the bridge between these two states. Robertson wonders – ‘Was he awake the whole time and posing?’ – in the commentary added in post-production. This question adds a layer of uncertainty – can we distinguish between the conscious and the unconscious? Maybe life and reality as we perceive it is only a dream? Or maybe one’s life is a nonlinear reality as Robinson herself states in one of the audio channels: ‘All is an illusion. <...> I don’t think that’s true. It’s a shifting reality.’ The reality is fluctuating and always changing – it is a flexible string, which one can bend or stretch. I thought that the linear time understanding truly does not fit our script. In general, it is unbelievably strange to still divide the thinking about time (or the timeline) in past, present and future while we agree that dualism has negative effects on the, let’s say, understanding of the self. Can you recall the part where I was explaining about french philosopher’s Deleuze’s construct of a crystal image (Deleuze, 1989)? Film-making is the junction between an actual image and its virtual image. The film is a crystal image. No wonder why, we chose the little reflections of a crystal in the ring to be the thread joining the stories and the viewer's perception of different realities.

I have been to an exhibition in The Photographer’s Gallery. They showed multidisciplinary artist’s Helen Cammock’s work (figure 4). The place was filled with black and white street shots but just on the other side of the wall, there was another space. It was a dark room with two projections of the same film. However, the projections were not synchronized. Only after a while did I get what was happening. It is the same piece with two films coordinated with each other shown at the same time. This inspired me to have several screens at the same time and make the viewer wonder, which one is the real one?

In Plato’s cave allegory the prisoner’s are chained in the cave, facing the wall. Behind them, outside of the cave, there is a burning fire and a path. What the prisoners can solely see is shadows of all the people, animals and chariots passing by. Sometimes I feel as if we are functioning as these prisoners, presented only with shadows of an ever-changing reality.

I am still pondering, if reality is shifting, how can we identify ourselves as ourselves? Now I would like to analyse Polish philosopher’s and sociologist’s Zygmunt Bauman’s idea of liquid identity (Bauman, 2000). So, coming back to it, the identity can be compared to the ‘fluidity just below the thin wrapping of the form’ (Bauman, 2000). The identity, according to Bauman’s theory, does not have a solid structure, just an outline, which is also fluctuating and changing over time.

Despite the inevitable change, one repels to see the transformation and holds onto the sturdy. Deleuze and Guattari (Deleuze, Guattari, 1994) argue that we are eager to intervene in the fluid nature of the identity with fragmented objects. Is memory one of those fragmented objects? I cannot help but wonder, maybe it is not an intervention – maybe identity is like a boiling soup, changing and transforming while boiling or cooling down although some of the ingredients stay the same. I cannot help myself but believe that the fluid nature of identity is not interrupted but supplemented by the fragmented objects. Sometimes they make up the majority of the space, sometimes – only a tiny fraction.

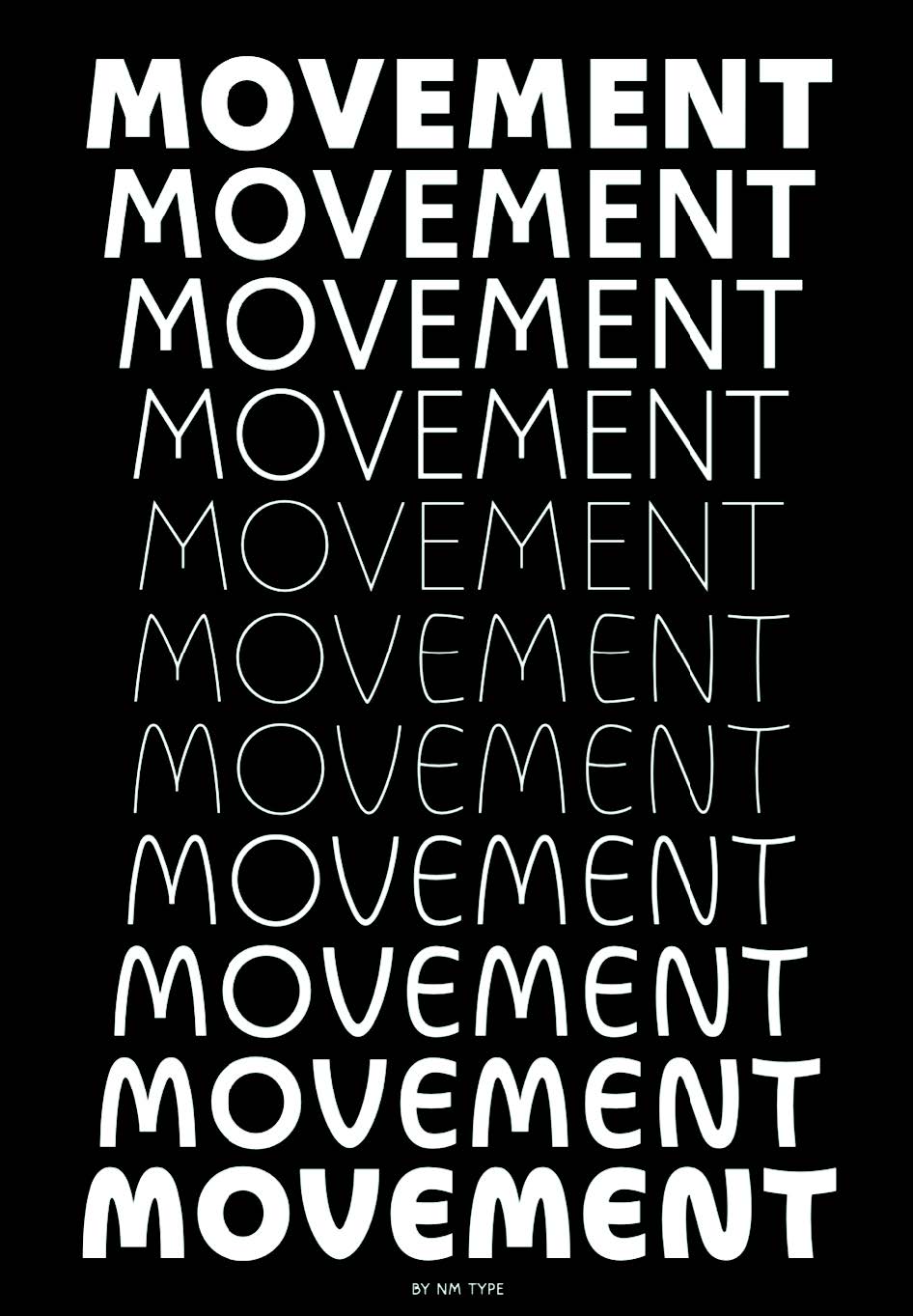

I was reading the daily news when an article of AIGA’s ‘Eye of Design’ popped up. As I thought earlier, I will include only relevant examples from the art of cinematography, I couldn’t leave this one out. The article presented a new typeface called ‘Movement’ created by the NM studio (figure 5). The studio collaborated with the choreographer Andile Vellem and Design Indaba. The letterforms were created by the shapes that appeared in the choreographed movements. Choreographer, dancer and movement theoritician Rudolf von Laban had developed theory that inspired the creators to translate the movement to the typeface. Body, effort, shape and space – the four categories that each have two opposites. The typeface gives an impression as the letterforms represent the human body which is moving and transforming. I never thought that liquid identity could be merged with embodiment and show the transformation in this incredibly simple yet so effective form.

Memory is one of the most powerful tools to provoke audiences (Rudnick, 2017). We are using this artifice in the script a lot. Luckily, memory is closely related to perception. English film director Derek Jarman (Jarman, 1995) in his book ‘Chroma’ discusses the perception of the colour red. If you have a red flag half facing the sun and the other side is in shadow, the colour will appear differently. So does the red from the flag actually change? While we see two different colours – one, bright red, in the sun, another, dark brown-red, in the shadow – we suppose that it is the same red. The office setting that we created in part two will not be shown in the film. It will exist though. In a different dimension – in the viewer's consciousness, in their imagination, in their memory. I would like to succeed in creating another reality, closely related to memory, which is no less real. As film-maker Wim Wenders recalled his encounter in Sydney: ‘Someone asked me after a screening of ‘Paris, Texas’: ‘Is that a true story?’ I said: ‘It is now’.’ (Wenders, 1996).

Motion picture pioneers Lumiere brothers in ‘L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de la Ciotat (Arrival of the Train at La Ciotat Station)’ – a 50-second movie – show a very well known occurrence of a train approaching the platforms, pulling into the station and passengers going from and to the wagons (first screening in1895). What made this short film so widely known? It is the spooked reaction of the viewers fleeing the room and hoping that the train won’t hit them. Hilarious, I thought. Although now I cannot help but wonder, isn’t that what all artists want? A strong reaction. The Lumiere brothers thought out the composition of the frame very carefully. They used a diagonal framing of the train approaching, creating even more depth. That’s what made the spectators so scared – it seemed that the train was truly going to crash into the room. A simple yet effective technique. Even the choice of a subject was banal, so it made the action of viewers fleeing from distress even more absurd. I think this reference is beautifully intertwined with the mesh of realities we are creating in part two. The absurdity of hating your job yet loving the trains so much, you cannot leave.

‘The web of trains is immaculately complicated…’ – Oh, I love this quote! Nice work.

Part Three

The monologue is carried through part 3. Person walks in the shot from the center, sits on the stool and concentrates to start the monologue.

(NARRATOR 3)

EXTREME CLOSE UPS OF NARRATOR’S 1 FACE FEATURES: LIPS, EYES, EARS, NECK. BACKGROUND IS WHITE. CLOSE UPS OF NARRATOR’S HAND ON THE LAP AND LEGS ON THE STOOL.

NARRATOR 3

Just a large Americano, please.

NARRATOR 3

(calm)

I sat on a bench in a park, while sipping my coffee. This small but peaceful green area seemed like a great refuge from the chaotic train station next door.

The sun was gently shining on my face, making me want to close my eyes and drift far away from everything. From all the mess and noise and senseless people. I stared at a young couple, walking their dog - a whippet, from what I could tell - dressed in a tiny, stone blue sweater. I began thinking what their life might be like, as my coffee cup warmed up my hands.

(distressed)

The old and dirty, tiled ground started gently vibrating as soon as I entered Kings Cross station. This forever crowded, musty and disordered scene was part of my everyday routine. With people repeatedly bumping into each other, rushing up and down from platforms, visiting the same tycoonowned chains, it all seemed like a simulation, a controlled chaos.

A tall woman, dressed in a grey suit was loudly arguing on her phone, while trying to find something in her - clearly expensive - tote bag. Five, loud, teenagers sat outside one of those excessively publicized coffee shops that make their coffee unnecessarily sweet and pricey. Right next to them, there was a woman, struggling to tame her three children - all running around trying to imitate trains. The ground started vibrating again.

(sarcastic)

People on the platform weren’t any less headsplitting. My train was supposed to be here in two minutes. I reached for my ticket, just to double check my seats, when I heard the heavy, metal wheels making their way towards my platform.

(surprised)

I couldn’t wait to sit in my quiet cabin and get some long awaited, peaceful time. As I was making my way to the last wagon, something bright flashed in front of my eyes. I stopped. Within milliseconds, I saw colorful light beams bouncing on the window of one of the cabins. I wanted to step closer and take a peek inside but I couldn’t move. It felt as if my feet were chained to the ground with heavy weights. My desire to see behind the red, velvet curtain covering most of the window, seemed to grow as the beams were dancing on the glass surface. And just like that, they were gone.

-END OF PART THREE-

Director's remarks for part three

In part three we are repeating the same metaphor of the light passing through space. A little glimpse of the ring which we described so accurately in part one. I could not help but wonder, what is time? Isn’t it just light passing through space?

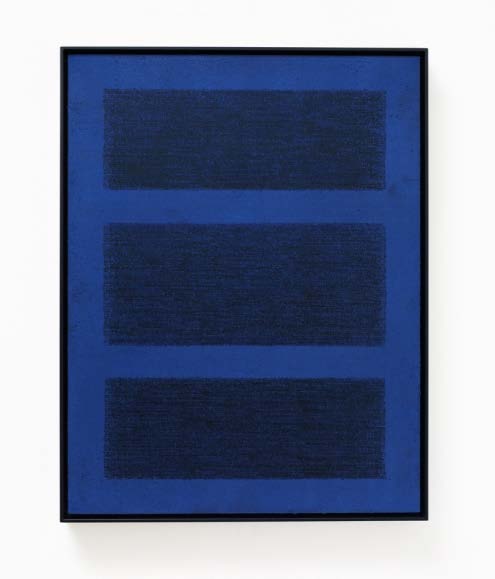

I found some interesting references regarding repetition and time. Look at this citation from one of my favorite photographer’s Klaus Rinke’s interviews: ‘I have always thought that photography was a break-in time. The photograph is corroded by the light. Death within appearance. That is what you can see here. You know, all my work should be analyzed as a meditation on cycles, on death, life and presence.’ (Rinke, 1972). There are several of Rinke’s works that I am fascinated by, however ‘De placement: Taking a Position in Time’ is one of my favourites. While observing the piece, one can easily sense the infinity of the presence and the frozen time. I have clipped the image to this page (figure 6). Another artist who is studying the concept of time is multimedia artist Idris Khan. ‘Infinite Lines’ (2019) is composed of a thousand overlapping lines of text stamped on a large blue panel (figure 7). What happens? The text is hardly legible. While repeating the same action Khan eradicates the meaning and time (Khan, 2019). Final artist and photographer that also conceptualizes the theme of time is Paul Rousteau. He freezes time in his high fashion shoots, using long exposure techniques (figure 8). In this way, images turn out blurred and the bodies of the models are distorted.

A visual artist and composer Christian Marclay in his major, 24 hour-long piece of work ‘Clock’, shown both at the White Cube (Mason’s Yard, London in October 2010) and Tate Modern (London in January 2011), display time in the most brutal form (Marclay, 2010). He spent several years picking up different scenes from multiple movies and glued them together according to the actual time they last. This way a viewer could use the piece as an actual clock to tell time. Despite that, ‘Clock’ does not have any coherence in the shots following each other. It disrupts the narrative as well as the spectrum of emotions.

I am using Robertson’s ‘Five Year Diary’ as an example to illustrate my thoughts one more time. I believe she makes a beautiful connection of time and body in her voiceovers: ‘I said we would live to the end of time. Living till the end of time – when the bomb on the sun explodes, we would go to a starship and travel, travel, travel, travel to another sun and start all over again. <...> I would remain myself till the end of time. <...> It was just the end of time before the beginning.’ The reality is stretched and wrapped, and the body becomes just a simple limitation in this time, after the end of time: ‘I became the body. And the body speaks to the body. And the body wants to be unburied.’ Mind, being extracorporeal, does have a limit at this time (or beginning, after the end of time) – the body. However, the body, being a limit, frees the mind, letting it travel and experience reality. According to french philosopher Merlau-Ponty ‘we perceive the world through our bodies, through being embodied.’ (Merlau-Ponty, 2005). We can walk around the space and perceive it from different points of view with the same body and set of eyes. I sometimes realize, when I walk around my flat, that each time I perceive this place differently. It is beautiful, isn’t it?

Do you remember that I promised to analyze Heidegger’s theory in more depth? Now is the time. Martin Heidegger was willing to transcend the dualism of mind and body. He came up with a construct called ‘Dasein’ or there-being. According to Heidegger, there are three elements of Dasein (Heidegger, 1962). First, Dasein appears in a world where it converges with cultural and historical practices, therefore Dasein is social. Second, the concept of Dasein explores the relationship between Dasein and language, which has a meaning, known across society. Finally, Dasein is self-reflective about its being and its placeness. The aforementioned three aspects help me understand better what Robertson meant when she stated that the body is an inseparable part of one’s mind and can free it, rather than imprison it.

PART FOUR: WHERE ALL THE STORIES MEET

The dialogue is carried through part 4. Person is already in the shot.

(NARRATOR 1, NARRATOR 2, narrator 3)

EXTREME CLOSE UPS OF NARRATORS FACES:

LIPS, EYES, EARS, NECK. BACKGROUND IS WHITE. CLOSE UP OF NARRATORS FACE, FULL FRAME, CANNOT SEE THE BACKGROUND.

NARRATOR 1

How many years are you dead?

NARRATOR 2

NARRATOR 3

I think you lost this. I am forty years old. With my grandmother’s ring on my finger. Its eye is looking dead straight into my soul.

-THE END-

Director’s remarks for part four, where all the stories meet

Japanese-American designer, curator and writer Andrew Blauvelt introduces the term ‘collective creativity' (Blauvelt, 2011). One of the most famous artworks that allowed the viewer to create the artwork itself is Yayoi Kusama’s ‘Obliteration Room’ (Kusama, 2012). The blank white room with white furniture and white objects was covered in thousands of colourful stickers in the shape of a circle, which were stuck by the public on whatever place they wanted (figure 9). I think we should identify collective creativity as appearing every day when we perceive and create different meanings to art or design pieces that surround us. ‘Visual and textual elements are in effect conceived together, interlaced with one another. <...> There are signs ‘among us’. This means that the visible forms speak and that words possess the weight of visible realities; that signs and forms mutually revive their powers of material presentation and signification.’ (Ranciere, 2002). After the film, I would like the viewer to be left in awe, questioning, what has just happened, what happens next. As there would be nothing left or on the contrary – everything opens up, after the screening. Perception is what charges this piece: we might be in control of how the film was shot, however, we are not in control of how the artwork is perceived.

Some artists who explored perception use repetition widely in their work. Film-maker and performance artist VALIE EXPORT (name is stylized according to the artist wishes) in her video installation ‘Splitscreen: Solipsismus’ is broadcasting a video of a boxer, who is boxing with his reflection in the mirror (figure 10). EXPORT questions, which image is the real reality? The one that is broadcasted on the wall, the one that is in the mirror, or both? She is using repetition of the image and retracting the meaning of the boxer – the sportsman is not an irreplaceable part of the concept,

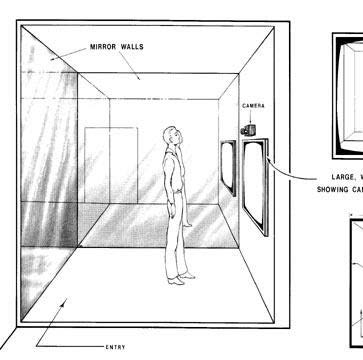

while his image being duplicated raises new questions of our perception and understanding of reality. I spoke about multidisciplinary artist’s Idris Khan's work before. He uses the very same principle – multiplying the text so many times that the text loses its initial meaning, creating a new one. Another multidisciplinary artist D. Graham in his installation ‘Present Continuous Past(s)’ (1974) explores how observing yourself in a TV screen recording (which broadcasts the mirror room with a delay of a few seconds) changes the perception of who I am and how I operate (figure 11).

I have come to an end. It was incredibly valuable to have taken the time to write these remarks. The writing helped me form my ideas not only in sentences but also in image form. I am immensely nervous to hear the feedback from the viewers but at the end of the day, I just hope there will be some. If the film left with them - there will be some.

Bibliography

- Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Berger J. (2001) Selected Essays Edited by Geoff Dyer. London: Bloomsbury.

- Blauvelt A. (2011). Tool (Or, Post-Production for the Graphic Designer). Published in Graphic Design: Now in Production. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center.

- Blouin ArtInfo (2013) In the Studio: Idris Khan “Beyond the Black” [video]. Available at: https:// www.skny.com/artists/idris-khan?view=slider#3 (Accessed: 7 November, 2021)

- Bourdin G. (2021) Various Artworks. Available at: https://www.guybourdin.org/artworks (Accessed: 7 November, 2021)

- Cammock H. (2021) Concrete Feathers and Porcelain Tacks [film installation]. Available at: https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/whats-on/helen-cammock-concrete-feathers-and-porcelain-tacks (Accessed: 28 November, 2021)

- Campany D. (2007) The Cinematic. Documents of Contemporary Art. London and Cambridge, Massachusetts: Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press.

- Cotton C. (2016) The Photograph as Contemporary Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Deleuze G. (1989) Cinema 2. London: The Athlone Press

- Deleuze, G., Guitarri, F. (1994) What is Philosophy? London: Verso.

- Descartes, R. (1641) Meditations 1&2. Available at: https://rintintin.colorado.edu/~vancecd/phil201/Meditations.pdf (Accessed: 7 November, 2021)

- Eastman G. (2016) A History of Photography. From 1839 to Present. Koln: Taschen.

- EXPORT V. (1968) Splitscreen: Solipsismus [film]

- Five Year Diary, reel 22: A Short Affair & Going Crazy (1982) Directed by: Anne Charlotte Robert- son. Available at: https://vimeo.com/340521179 (Accessed at: 7 November, 2021).

- Graham D. (1974) Present Continuous Past(s) [film]

- Heidegger, M. (1962) Being and Time. New York: Harper & Row.

- Jarman D. (1995). Chroma. A Book of Color. New York: The Overlook Press Woodstock.

- Kasuba A. (1971-1972) The Live-In-Environment [installation]

- Khan, I. (2019) Infinite Lines [oil based ink on gesso and aluminum panel]. Available at: www.skny.com/artists/idris-khan#3 (Accessed 7 November, 2021)

- Kubrick S. (2015) New Perspectives. London: Black Dog Publishing.

- Kul-Want C. (2019) Philosophers on Film from Bergson to Badiou. A Critical Reader. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lanthimos Y. (2019) Nimic [film]. Available at: mubi.com

- Lawlor L. (2019) Jacques Derrida. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/derrida/ (Accessed at: 7 November, 2021).

- Lupton E. (1998). The Designer as Producer. Published in ‘The Education of a Graphic Designer’ p.159-162. New York: Allworth Press.

- Marclay C. (2010) The Clock [film] Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/marclay-the-clock-t14038 (Accessed at: 7 November, 2021).

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2005) Phenomenology of Perception. London and New York: Routledge.

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Mise en abyme. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mise%20en%20abyme. Accesed at: November 28, 2021

- Mitry J. (2000) The Aesthetics and Psychology of the Cinema. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Morley M. (2021) Typography Dancing Like It’s Never Danced Before, Thanks to Variable Font Technology. Available at: eyeondesign.aiga.org. (Accessed: 7 November, 2021).

- Perretta I. (2019) The Destructors [film]. Available at: https://vimeo.com/360562795# (Accessed: 28 November, 2021).

- Ranciere J. (2002) The Future of the Image. London, New York: Verso

- Rinke, K. (1972) De placement: Taking a Position in Time [photograph]. Available at: http://klausrinkestudio.com/the_work/index.html#Photography/1 (Accessed: 7 November, 2021)

- RNDR.studio (2020). Type/Dynamics. Interactive installation and exhibition at Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Rndr.studio [Online]. Available at: https://rndr.studio/projects/type-dynamics/ (Accessed: 7 November, 2021).

- Rousteau, P. (2020) Hermes FW2020 [photograph]. Available at: https://www.paulrousteau.com/fashion/le-monde-dhermes#paul-s-selection-6 (Accessed: 7 November, 2021)

- Rudnick D. (2017). Crisis of Graphic Practices: Challenges of the Next Decades. Youtube.com [online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ejp4AvetSA (Accessed: 7 November, 2021).

- Rush M. (2003) Video Art. London: Thames and Hudson

- Sontag S. (2002) On Photography. London: Penguin Classics.

- Tate.org.uk (2020). Yayoi Kusama’s Obliteration Room. Tate.org.uk [Online]. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/yayoikusama-8094/yayoi-kusamas-obliteration- room (Accessed: 7 November, 2021).

- Wenders W. (1996) The Act of Seeing. London and New York: Faber and Faber.

Appendix

Figure 1: Scheme of ‘crystal image’, concept by G.Deleuze

Figure 1: Scheme of ‘crystal image’, concept by G.Deleuze

Figure 2: Screen photograph of the film ‘The Destructors’, directed by I.Perretta

Figure 2: Screen photograph of the film ‘The Destructors’, directed by I.Perretta

Figure 3: ‘The Live-In-Environment’ installation by A.Kasuba

Figure 3: ‘The Live-In-Environment’ installation by A.Kasuba

Figure 4: ‘Concrete Feathers and Porcelain Tacks’ film and installation by H. Cammock

Figure 4: ‘Concrete Feathers and Porcelain Tacks’ film and installation by H. Cammock

Figure 5: ‘Movement’ typeface specimen by NM type

Figure 5: ‘Movement’ typeface specimen by NM type

Figure 6: De placement: Taking a Position in Time by K. Rinke.

Figure 6: De placement: Taking a Position in Time by K. Rinke.

Figure 7: Infinite lines by I. Khan

Figure 7: Infinite lines by I. Khan

Figure 8: Hermes FW2020 by P. Rousteau

Figure 8: Hermes FW2020 by P. Rousteau

Figure 9: Obliteration room by Y. Kusama

Figure 9: Obliteration room by Y. Kusama

Figure 10: Splitscreen: Solipsismus by VALIE EXPORT

Figure 10: Splitscreen: Solipsismus by VALIE EXPORT

Figure 11: Present Continuous Past(s) by D. Graham

Figure 11: Present Continuous Past(s) by D. Graham